That there is a major issue with gender representation within both gaming and literary culture is now so widely accepted that it’s easy to forget the claim is even contested. But contested it is; the worst that can be said about Anita Sarkeesian‘s Tropes vs Women series so far is that it’s a succession of statements of the obvious, but that hasn’t prevented a wave of antipathy and attempts to discredit Sarkeesian, even to the point of publicly accusing her of fraud for asking for too much money from her supporters.(1)

Even if we ignore this resistance to eminently sensible criticisms, just because a problem is widely acknowledged doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be discussed. One argument deployed when feminist critics like Sarkeesian emerge, or when statistics are released that point to comparable problems in literary culture, is that we’re only seeing a reflection of wider problems with equality in society. Games developers cannot employ more women if women aren’t applying for the jobs and female authors can’t be published if they aren’t submitting work. Similarly, if there is a lack of female protagonists, characters and perspectives in games and literature, it’s because the public aren’t interested enough in them.

Firstly, it should be pointed out that this is a case of neutrality as complicity. The metaphor of the travelator(2) is useful in characterising what’s happening. There is a cultural drift towards inequality – not just to the detriment of women, but to the detriment of minority ethnic groups, the poor, gay people, transsexuals, the disabled and others. We can debate about who is responsible for that cultural drift and whether or not it’s part of human nature; what’s important for now is to understand that if you aren’t resisting – if you aren’t walking in the opposite direction along the travelator – then you’re being pulled towards accepting greater and greater inequality, into a position where you’re more likely to find basic notions of freedom and fairness unrealistic or fanciful. The most common complaint against feminists is that they’re too visible, too attention-seeking, too forceful. This complaint ignores cultural drift and the fact that you can’t create a countercurrent without considerable noise and activity, nor without making demands.

Secondly, literature and gaming in particular should be at the forefront of positive change. Games are spaces where we can play. Books are spaces where we can exercise our imaginations. Creative mediums are where we can take stock of what is unhealthy in our world by imagining a better one, where we can test outlandish theories, and explore our most dangerous instincts in a safe environment. They’re where we can visualise and articulate internal conflict. In short, they’re areas where notions of what is realistically achievable in society should give way to idealism and social experimentation, where everything we think we know should be regularly turned on its head. This already happens; it just needs to happen more.

More importantly, they’re areas where change can occur relatively rapidly because of their accessibility. In most industries, systemic prejudice is so ingrained, so threaded into the system that change is generational at best. Women don’t land corporate jobs, often, because they lack the requisite aggression and competitive edge. They lack aggression and a competitive edge because these are qualities that, early on in children’s development, are identified as masculine, as unfeminine. In other areas, women lack qualification or experience or self-assurance, all because they are undermined at an early point in their lives and placed at a disadvantage. But you don’t need to land a job to become a writer. And with game creation tools like Twine and Construct 2 constantly evolving, you don’t need a job in technology to become a game developer. Best of all, the Internet provides the necessary tools for disseminating the resulting work and building an audience for female critics and creators alike.

|

| Twine is a simple, window-based development platform for text adventures. |

So what needs to be done?

One of the most important things to challenge in both literature and gaming is the idea of a type of book or game that is aimed at women, and the accompanying notion that addressing the gender imbalance will mean more of these types of games and books, at the expense of the type that we (men) typically enjoy. The scare story is that political correctness demands an overall reduction in quality.

But these are industries/environments where the full spectrum of what appeals to boys and men has been heavily explored and is collectively well understood, while women’s tastes are very poorly understood, in part due to a deficit of widely disseminated critical writing by women. The kind of games and books that are marketed to girls and women – chick-lit and dolls’ house games – are the result of this poor understanding. That’s not to say women don’t like these games and books, but that it represents only a tiny part of the full spectrum of what they might like – a spectrum which, in all likelihood, overlaps to a massive degree with men’s tastes.

If women’s tastes were more thoroughly explored and understood, what I suspect would come to light is that a multiplicity of minor changes would do much to bring more women on board while sacrificing little of what appeals to male audiences. To take an example from gaming, one of the reasons women can feel excluded by the content of a game is the proliferation of female characters whose sole purpose appears to be titillation. This is frequently misunderstood as an objection to partial nudity or attractiveness, when in fact it’s a complaint about deficit of personality and relatable goals. It would be easily resolved by introducing female characters who fill out a much wider range of roles, as well as genuinely sexy male characters. It does not necessitate censorship.

|

| GLaDOS, one of gaming’s most unusual and memorable female characters. |

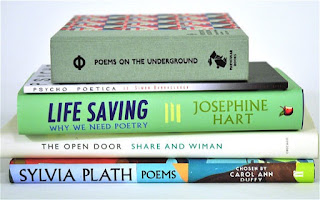

Although literary culture prides itself on sophistication, there is a similar issue with crude understanding of what women want and what is distinct, if anything, about women’s writing. Famously, VS Naipaul last year attempted to reduce the entire scope of women’s fiction to ‘sentimentality, the narrow view of the world’. If this isn’t a clue as to a greater problem in how we envisage women’s role in literary culture, I don’t know what is. Even within poetry, there is a barely-remarked-on but, in my opinion, noticeable stylistic pigeonhole that women’s writing slots into. Women who write in this way (broadly: confessional, relationship-focused, formally loose) are, in my judgement, more likely to be published than women who write in any number of other ways. I would suggest that there is a subconscious, male-led selection process at work that highlights this style of poem as ‘representing’ women better than some of the other styles women choose to write in.

Let’s address the argument that better representation of women in either medium means a drop in quality, means opting for the poorer candidate to fulfil a quota. Women make up over half the world’s population. There is no scientific basis for the assumption that men are more intelligent, more creative, more individualistic or harder-working than women. If you have two local sports teams who, in totality, are equal to one another, and you make up a national side that is heavily weighted to one of those teams, as a matter of logic, you must have picked the weaker players from one team at the expense of stronger players from the other. In any culture, subculture or industry where the gender balance is skewed heavily in favour of men, the weaker candidates are already being picked. More equality should logically amount to higher quality.

Finally, I want to say a few words about Coin Opera 2: Fulminare’s Revenge and our approach to gender equality. The final ratio of contributors is 23 male to 18 female, which is 57:43 in favour of men. I consider this not ideal but within the boundaries of acceptability considering our limited resources. During the process of soliciting poems, three male poets approached me with unsolicited poems, while no female poets did. At one point, I did make a concerted effort to get more female poets on board because I felt we didn’t have enough. Not one female poet turned us down on the basis that she didn’t play games, and the games they played ranged from pinball tables to Skyrim. Some found that the games they wanted to write about had already been covered, and so declined. One, whose relationship with games was mostly through her children, specifically bought and played the game they wanted to write about for the first time, in the interests of getting a more in-depth perspective. Some poets of both sexes said they would have a think but ultimately didn’t get back to us.

I would say that, on the whole, the collection is definitely richer for its inclusion of a good number of female poets and gamers and that their work does not betray any notion that there is a strict segregation of tastes or styles between men and women. I don’t think of this as providing a service to women (albeit I hope that providing a platform for more women to respond to games and gaming is helpful) but as something that improves the overall quality, accessibility and range of the book.

Further links

Coverflip: Maureen Johnson on gendered book covers

Jane McGonigal, game designer and games culture activist

Helen Lewis writing in the New Statesman on female protagonists in games

Footnotes

(1) Prior to writing this article, I’d only seen the fraud accusation made in the seething jungle of comments sections on news sites. But I only had to type ‘Sarkeesian fraud’ into Google to find this page in the top two results.

(2) I first stole and redeployed this metaphor here.