Over the coming weeks we’ll be publishing a series of articles investigating the existing crossover – and the further potential for crossover – between games and poetry.

This week, Rebecca Wigmore is your guide to the smokey jazz clubs that skeletons inhabit in GRIM FANDANGO.

When

Grim Fandango was first released in 1998, I was a mere slip of a girl, amped up on almost a decade’s dedication to LucasArts’ point and click adventure game empire. From the zombie-beauty-queen antics of

Day of the Tentacle to what I regarded as the nigh-on-flawless

Monkey Island trilogy

1 LucasArts were the beginning and the end of the adventure game genre. The beauty part was this: you could not die

2. Freed from the tiresome burden of mortality, you could guide your archetypal nerd, gumshoe dog or wannabe pirate around what were, in the best games, fully realised worlds. You could look at anything, touch anything and be rewarded with a snappy piece of dialogue, a subtle clue and, often a great gag. The puzzles were labyrinthine and ingenious, but the biggest pleasure for me was wandering around a world.

This is the legacy of Tim Schafer, who started at LucasArts co-writing

Day of the Tentacle and the first two

Monkey Island adventures before being handed sole creative control of his own projects, including his masterpiece,

Grim Fandango.

You might want to watch this. It establishes tone. I don’t have the wordcount to establish tone. I’m busy.

The quality of the writing and the thrill of incidental discovery was the reason these games had such a powerful replay factor – a sort of novelistic pleasure in inhabiting a wholly authored universe, coupled with what David Lynch calls “space to dream.” There is a deeply satisfying tension between the driving narrative force of the puzzles and the more abstract pleasure of wandering about, luxuriating in language and incidental space. LucasArts adventure games were certainly what the immersive theatre/tech crowd call “on rails”, in that the player had one route to one ultimate goal (solve puzzles, progress the story) but the experience of playing was so leisurely and ambulatory in nature it’s little wonder that Grim Fandango is often heralded as the pinnacle of the form. For it is here, in this world, that the gamer encounters the ultimate expression of LucasArt’s adventure gaming philosophy: they play as Manny Calavera, a jobbing grim reaper cast in the Día de los Muertos mould; a literal undead flâneur.

Baudelaire would have made an excellent skeleton.

“Well, I have a poem I wrote just for you. Pay attention because it’s pretty short. Here it goes: Ch-ch-ch-u-u-u-u-u-u-u-u-u-u-u-mp.”

As Jon said in the

first post in this series, inserting poetry into games seems to have a function that sits outside of the purely ludic: to give a sense of narrative texture, a sort of shorthand for folklore and

history.

Grim Fandango‘s universe is alive with poetry, where it functions as a way to give the game’s universe a rare texture and history, build character and puncture pomposity, a conceit that is set up early on in the game (indeed this puzzle formed the game’s demo way back when PC Gamer had corporeal giveaways on its cover) when Manny has the option to ask the balloon artist to make him a balloon in the shape of a cat, a dingo or a famous poet. The puzzle requires that Manny pops that balloon to scare away some aggressive pigeons. Now, if you can get through life without enjoying the phrase “Run, you pigeons, it’s Robert Frost!” then I admire your austerity but ultimately, I pity you. This puzzle sets the game’s tone: knowing but willing to prick any pomposity, whether it be from the Old Guard or from phony anti-establishment types.

You can see the likeness. Balloon pipe and everything.

The War on Beat Poetry

Let’s look at the this segment now, which is just under halfway through the game’s four-year structure. Year Two: Rubecava.

In a brief bit of scene-setting, Rubecava is a maritime town that functions much the same as Casablanca, with Manny adopting the persona and suave white dinner jacket of Humphrey Bogart. Unlike Bogie, however, Calavera is going to give it all up and pursue Meche, the virtuous woman, who should have got a free ride to The Other Side but, for reasons way too Byzantine explain here, Manny doomed to walk a treacherous path to salvation alone. The noirish mood of Rubecava is very much

Casablanca,

Chinatown and

On The Waterfront whizzed up in a blender, in a temporal space that seems to occupy about four decades at once (a move which seems appropriate for a game set in Purgatory). However, in the scene that we are looking at, it is very much the 1950s, with the spirit of Ginsberg hanging in the air. Manny must visit The Blue Casket, a beat poetry club where

– surprise, surprise

– it’s open mic night.

The game has a lot of fun with the club’s beatnik audience – “Hola, trust-funders!” – but one of the true pleasures of this segment is your interaction with Olivia, the owner of the club, and her subsequent performances.

You can watch the performances here. They are accompanied by very excited gamer commentary,

which adds to it, somehow.

Olivia’s first two performances are exemplars of the kind of performance poetry that often infuriates: lotta poetry ‘voice’ and vague aphoristic-sounding half-jokes that barely scan:

I called my cat “Boney.”

‘Til she said it wouldn’t do

I said, “Why?”

She said, “Sister

‘Cuz that’s what I’VE been calling YOU!”

That extra syllable that ‘Cuz’ provides in the final line is maddening, although the spoken delivery of the poem means that the player glides fairly easily over it. The voice acting in Grim Fandango is uniformly excellent and the work of Paula Killen, who voices Olivia, does a lot to elevate the poem’s stature. Olivia’s cat poem was never intended for the page – the transcription is from the game’s subtitles, the capital letters functioning as performance note more than anything else – direction that Killen thankfully ignores. The rest of Olivia’s poems are the same kind of beatnik pastiche until we reach her final poem:

With bony hands I hold my partner,

on soulless feet we cross the floor,

the music stops as if to answer

an empty knocking at the door.

It seems his skin was sweet as mango

when last I held him to my breast,

but now we dance this grim fandango

and will four years before we rest.

I want you to understand how much this thrilled my 15-year-old self and, in truth, how it delights me still. This is one of a handful of poems in Grim Fandango that have a function beyond character-building and laughing at how lame bad performance poetry can be3. This poem, which serves no function from a gameplay standpoint, is the only point in the entire game in which the title is mentioned at all. It would be easy to bypass it entirely if you were focused on beelining through the puzzles. “Grim fandango” is a wondrous phrase, an iambic delight and one of those rare titles that seems to contain more the more you consider it – yes, it’s literally a dance of death, which calls to mind the herky-jerky climax of The Seventh Seal, the rhythmic contradiction of this frenetic and joyous couples’ dance being invoked in a poem with a slow, thunking heartbeat of a meter. For the first time there is imagery that extends beyond a punchline or narrative set-up. There is something sensual and vaguely upsetting about skin-as-mango-flesh: exotic and heady, yes, but also something that drips with moisture, easily rent from the body. There is a pun and palpable despair in the “soulless feet” that cross the floor.

Ludologists Are Vomiting Mango Chunks As They Read This.

The ease with which Grim Fandango manages the drastic tonal shift from beatnik comedy bits to the mortal wrench of the final poem is one of the arguments I can make for this game as art. You could make a similar case for Portal 2, although that rather worryingly betrays my origins in the traditional humanities department. Non-ludic narrative world-building is only an aspect of digital gaming and one that is certainly not essential to the artistic success of any given number of games. Yes, poets have embraced him but Pacman does not have a richly imagined in-game social history. There is no moment where you can instruct Pacman to ‘use’ the moon, as you do Manny in Grim Fandango, and be surprised by his recitation of a simple, Poe-ish verse. There is no purpose to this action another then that shock of pleasure at uncovering what appears to be a moment of shared folklore as the NPC sailor joins in with the final gothic couplet:

This isn’t Pacman’s schtick at all. Its pleasures are visceral as part of a carefully designed and programmed feedback loop of input from player and output from game. There isn’t the poet’s space to dream in this kind of game, unless it is created externally. Indeed, if you start reading old-school academic analysis of computer games, it often reads starkly irrelevant. Like using the same aesthetic criteria to evaluate Jaws as you would Moby Dick – they might have a crossover but dude, they’re different animals, always.

There is much more to say about Grim Fandango‘s use of poetry – we haven’t even gotten to the player-created in-game performance poems – and I will continue in PART TWO.

1. Let us gracefully draw a veil over subsequent instalments. Very few things were meant to have quadrilogies. The Fast & The Furiousseries is a notable exception to this rule, Vin Diesel more than anyone understands the profound, self-replicating beauty of a fractal.

2. There are exceptions to this, most notably the Indiana Jones game series.

3. Both entirely worthy aesthetic pursuits.

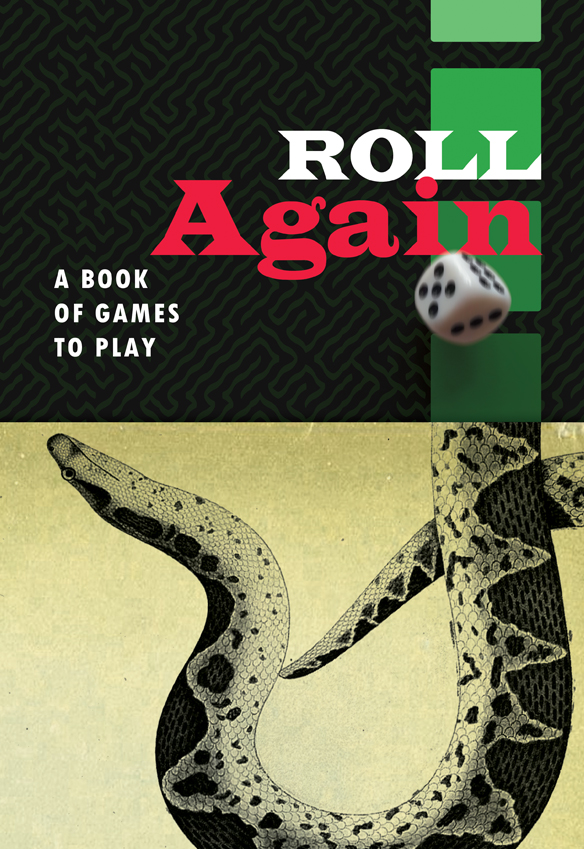

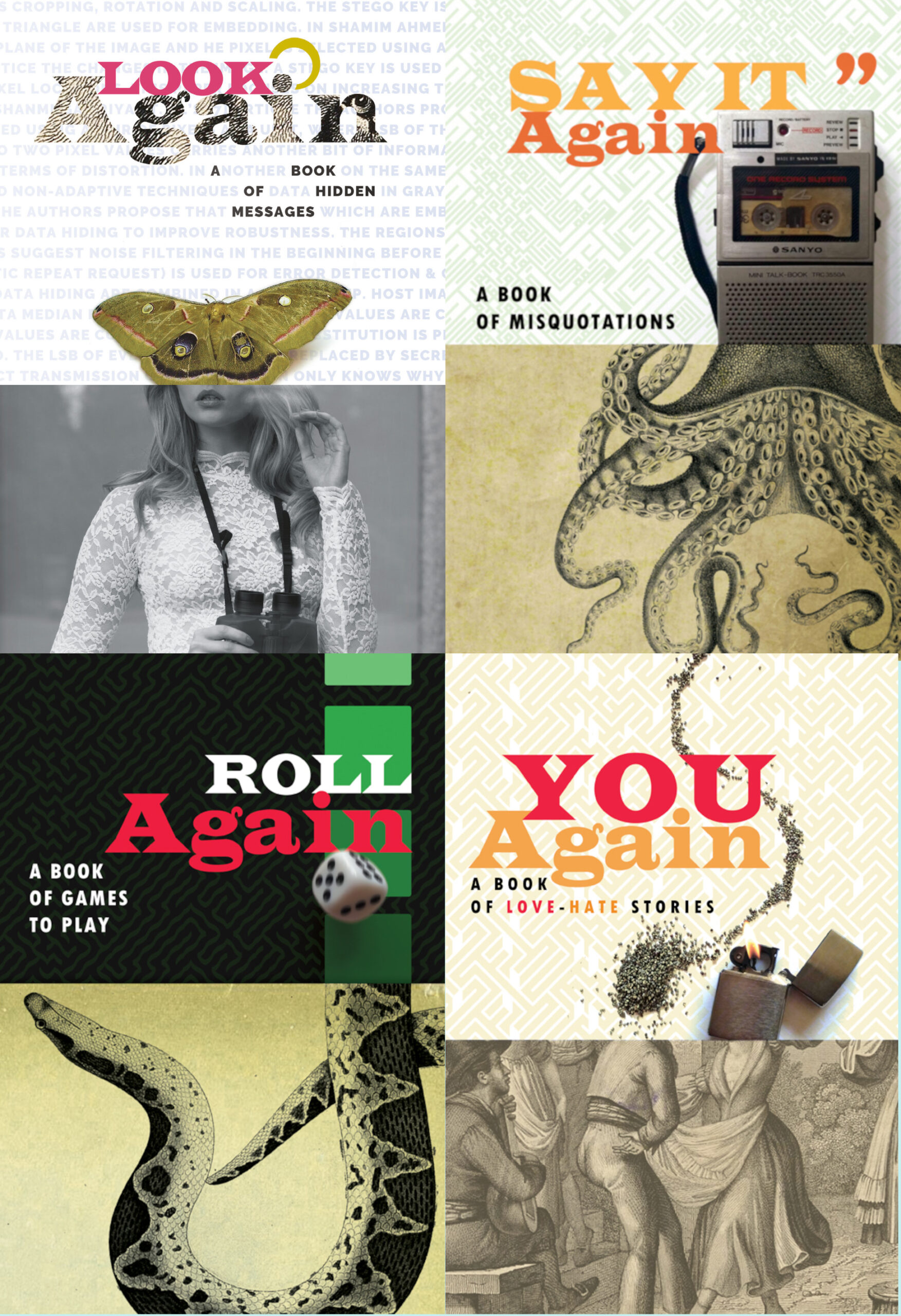

The four new books are:

The four new books are: