THE NUMBER of poets writing today,

it’s frequently argued, is reaching a kind of critical mass. Our finest are being buried in mediocrity, and the bulk of what is being written is ‘

landfill‘. Who gassed the gatekeepers? What blunts the blades of the critic-gardeners, so that our flowerbeds are choked with dandelions? How will future generations pick through the mess?

❖Another way of looking at it❖

This angst over the quantity of poetry being published is really the result of the limited way we’ve come to talk about poets, poems and poetry. As the number and diversity of its practitioners flourish, still we repeatedly fall back on the trope of the giant among men, the axe smashing the ice, the quality of ‘greatness’, to describe the value and appeal of what is being written. I don’t mean in one specific mode of exchange either – this need to elevate is a common denominator in publicity, criticism and casual conversation. Elevate, that is, in lieu of meaningful differentiation.

The result is the appearance of multitudes laying claim to the same tiny throne, with no point of reference for what is described beyond other, weaker variations of itself. You do not expand your audience by saying, “This is the best kind of what it is” without saying what ‘it’ is. You simply create the impression of a mass of sameness.

The marketing of poetry in particular reveals that we struggle to move beyond the comparative, and come armed with only limited ways of illustrating its effects. Too many book blurbs deploy a smorgasbord of stock traits while simultaneously laying claim, through bare assertion, to uniqueness. This runs through to our reviewing culture as well, which frequently constitutes an ever-more finely balanced game of using different words to convey the same message. Think, for example, how many poets reportedly fit a description along these lines:

ceaselessly inventive and original, utilises precise, finely wrought language, deft musicality, addresses themes of identity, place, change in luminous, startling lines, often wry and funny, unafraid to take risks – in short, the real thing.

Yes, this goes beyond claims to grandeur and eminence, but the repetitiousness of such depiction doesn’t get us very far.

The fatigue felt all round is, therefore, not a reflection of the sameness of the poetry itself but its presentation, and we’re fooling ourselves if we ignore how much of our own impression is informed by that consistency of presentation. This accounts for a range of apparently small-minded behaviours – from the self-styled representative of ‘ordinary people’ who dismisses whole generations for abandoning formal conservatism, to the finely articulated manifesto as to what constitutes ‘real poetry’, to the frustrated avant-gardist who disavows anything with a narrative pulse. All means of avoiding tangling with the unruly cosmos of poetic possibility, most of which lies unknown and threatening beyond the shallow sweep of our descriptive language. To know much of it well requires a dedicated and thorough immersion that is beyond most of us. Instead, we tend to find our own corner of a friendly star system, settle on a hospitable planet, and turn our telescopes inward, while the public at large clings tightly to the safety of school-taught verse.

❖Taking cues❖

What we should be doing is making our cosmos navigable, not just for ourselves but everyone outside of poetry – so not merely to the person who is prepared to burrow through hundreds of academic papers but also (and more importantly because these are more numerous) the person browsing a bookshop display or events listing. I may have poked fun at the clichés of poetry selling five years ago with

Vitally Urgent: The Game of Blurb, but I’m not for a moment suggesting it’s easy to find ways of articulating the individual qualities of a poet or book so that they can be understood at a glance. Look across, however, at some of the mediums and genres whose audiences have expanded exponentially over the last few decades: manga, anime, games, science fiction and fantasy. These are areas – if not industries – which afford roles and employ to thousands of creators, filling large convention halls with fans who will queue for autographs from writers of all ages. It would be somewhat delusional to imagine that poetry could transform itself into a similar model of success, but we might at least pick up a few lessons in breaking out of a niche.

One such lesson is what I’d call the Character Select Screen Principle. Character select screens have appeared in certain genres of computer games since the days of arcade cabinets, typically proffering an array of protagonists, one of which the player must select as their avatar. They are designed to convey, in as immediate a manner as possible, the fundamental traits of each character, so as to help the player identify one which suits him or her best. Posture, expression and clothing, as well as numerical statistics and brief biographical information, are employed as suggestive devices – broad strokes that serve to make a memorable impression.

What the character select screen appeals to – and what, in their different ways, so many pop culture properties make use of – is our need to explore, develop and demonstrate our identity through the choices we make. We pick favourites – to play, to root for, to fantasise over – as a way of describing who we are, to ourselves and our surroundings. Witness also the proliferation of ‘Which ___ Are You?’ quizzes on Facebook, the results of which are shared for comment. The significance of a choice shouldn’t be apparent only to ourselves but to those who see we have made it.

In other words, people are more likely to buy and read poetry if their choice of what to read tells other people something about them.

❖And where do we start? ❖

Both cover art and cover copy are already used to accentuate the individual flavour of a poetry book, with varying degrees of success. Publisher livery can serve as an obstacle (all Carcanet books are predominantly red, black and white) or provide a framework. It’s fair to say that Faber have at their disposal a simple but effective means of distinguishing their poets (and their poets’ books) from each other, by using colour as the major design feature of their cover design, harking back to one of the very first ways we learn to mark our identities as children, by having a favourite colour. Some poets – Luke Kennard and W. N. Herbert come to mind – have a talent for cartoonifying themselves. All of this is good groundwork.

The most successful critical analysis also strives to find ways of describing its subject that make a lasting impression. In fact, I’d go as far as saying that this is the major useful function of a review. In a world where we simply do not have a practice of poetry criticism that is sufficiently removed from the writing and publishing of poetry, memorable description is more important than maintaining the cracked illusion of critical distance. In other words, a bad review that paints a striking portrait of a poet or collection is providing more of a service to the poet, and to readers, than a good review that deals in subtle nuances. To the extent we believe our critical culture is a project of assessment – of holding gemstones to the light and rating their flawlessness – we are mistaken. Its value to us is as a way of generating the ingredients for our own character select screens – simple, stark phrases that colour one poet or book differently from another – even if this function is too often buried beneath politesse and the affected gestures of judgement.

What I suggest, therefore, is a project, building on these beginnings, towards broad-stroke characterisation – of poems, poets, poetries, books – with the measure of success being this: that the person browsing the bookshop display be able to skim their eyes across a range of covers and brief descriptions and, even if they aren’t generally a buyer of poetry, be able to pick a personal favourite.

❖Objections?❖

(1) Look, Jon, poetry is about subtlety, the slow release of flavour. This is vulgarisation you’re talking about – caricaturing, turning books into fashion accessories.

Answer: Such subtlety can be over-fetishised – it isn’t fundamental to the art form. I also think it’s wrong to be disdainful of instantaneous appeal or announcement of purpose. It is a great thing to fall in love on sight.

(2) It’s not up to us to ‘sell’ poetry, Jon. People just need to be made less ignorant and less fearful of reading difficult texts.

Answer: Avoid the responsibility if you want, but remember, this isn’t just a problem of poetry’s public image; most practitioners and critics also seem to struggle to know what’s happening in their own art beyond a narrow area of focus. Especially the ones who think they know everything.

(3) What you’re asking for is already under way.

Answer: I agree; there are people already on the case. But this should be something many more of us are involved in and thinking about, because it goes to the way practitioners conduct casual dialogue amongst themselves as well. My experience now is that we mostly say to each other that someone or something is ‘good’, ‘interesting’, ‘clever’, ‘overrated’, ‘underrated’, and so on, in a way that makes poetry seem like an exercise in merely perpetually impressing each other – exactly what its most acid-tongued critics accuse it of being.

(4) What of the dangers of poets becoming typecast or straitjacketed by this so-called ‘broad-stroke characterisation’?

Answer: It’s always possible to reinvent yourself.

❖Examples❖

Since I should practice what I preach, I’m now going to try to sketch some of my favourite poets, on the understanding that I make no claim to critical or objective distance in what follows. You can’t trust me as an impassive assessor, but that’s not the point of the exercise. The point is: bold descriptions that accentuate individual flavour.

J

OHN C

LEGG.

Insatiable collector and exhibitor of curiosities. In person, he’s half lion, half mad librarian, fizzing with a seemingly inexhaustible knowledge and excitement that spills into his poems. But you can never be sure whether the specimens he proffers with such wild enthusiasm are genuine finds or brilliant fakes of his own making.

Antler, his first collection, is a dusty display case of relic-tales, fragments and charms from lost and imagined civilisations, sometimes crossing into our own.

The True Account of Captain Love and the Five Joaquins is his versifying of an Old West yarn about a coward who carries a horse-thief’s head in a jar. Or is it?

K

IRSTEN I

RVING.Monsters and monstrousness is her area of expertise, via sex, lore and sci-fi. She throws herself at her subjects like a fireball – the resulting poems are rough-edged and crooked, like circus freaks or recalcitrant schoolgirls, too thorny and untrimmed to fit neatly among the more rarified species of poetry. They tend to land you in the middle of storm-struck emotional terrain without a map, revealing their context (and their teeth) gradually, through rows of jagged imagery. The giants, robots, cannibals and cartoon characters of her first collection,

Never, Never, Never Come Back, aren’t jolly pop culture references but portraits of outsiders made beautiful and terrible by what they lack.

T

ONY H

ARRISON.

For a brief moment in the 80s, Harrison was a notorious poet – the result of a televised version of the sprawling, angry

V, a long poem which ventriloquises the expletive-filled diction of a disenfranchised teen as it expounds on decay and societal fracturing. Tories wanted it banned. But for all the rage and sorrow that informs his best work, Harrison is formally conservative, somehow condensing extreme rawness and bitterness into tight rhymed couplets. You want direct? He’ll tell you what he thinks, how he feels with the force of someone jabbing a finger at your sternum. You want personal? Much of his oeuvre is effectively an autobiography of working class displacement and the splintering of his own identity.

C

HRISSY W

ILLIAMS.What the half-Italian Williams makes are more poems than anything else, but they’re also hybrids and creatures, the genes of other textual forms (mixtape, diary, screenplay) spliced with those of poetry. It’s all gone about with joyous, youthful abandon, so that each piece jitters like a matchbox of jumping beans. Her work so far comprises a string of opuscules – stealth raids made from the territory outside the formal poetry ‘collection’.

The Jam Trap is a sequence of rapid-fire comic vignettes.

Angela, her collaboration with artist Howard Hardiman, is a love letter to Angela Lansbury in the form of a nightmare-ride through her psyche.

Epigraphs is a work comprised solely of epigraphs.

The above do not represent a radical new way of writing, and could stand to be sparer and more direct still, perhaps shortened to the length of a cover quote. But as it stands, and to the extent they are effective, this approach is currently vastly outweighed by the glut of writing on poetry that proclaims ‘major contribution’, ‘finest of his generation’, ‘intense originality’, ‘unblinking’, ‘extraordinary’, ‘remarkable’ and so on and so forth, even down to those biographies we circulate which do little but count out awards.

How will future generations pick through this mess? Don’t make them test dozens of similarly-worded claims in search of some pantheon. Give them a landscape peopled with innumerable well-drawn characters who are as diverse as any group of people in the whole of humanity. And grant the same to the present generation.

***

Still not got your fix? Find the full post series here.

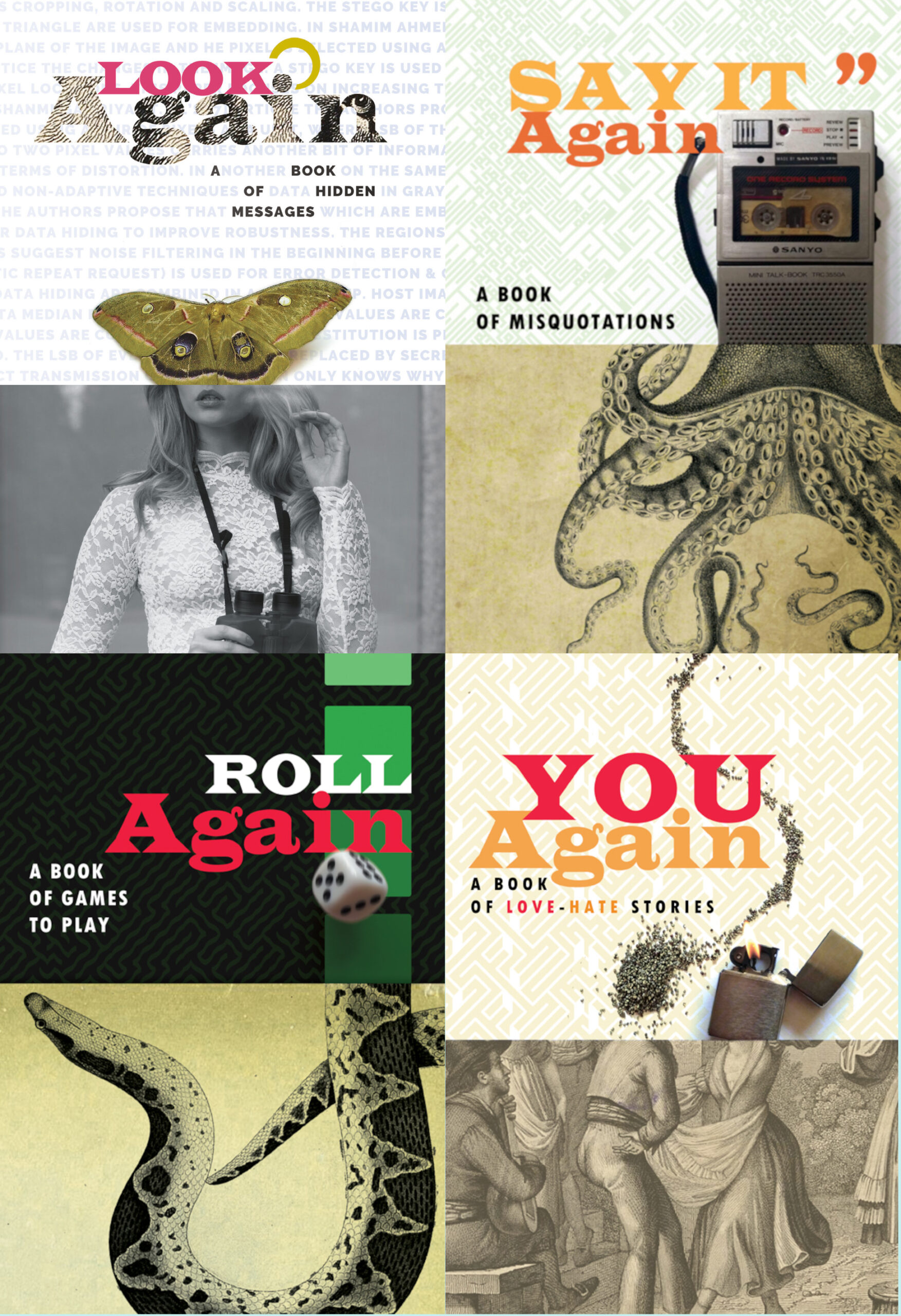

The four new books are:

The four new books are:

The incomparable

The incomparable