and a number of the real life astrophysicists who contributed work. Tickets are £8 and can be bought from the Royal Museums Greenwich website

.

Ahead of this exciting trip into other realms, we thought we’d explore the inside of the editor’s head, interviewing Simon about spare spaceships, kamikaze deer and smashing the science/art binary.

Where did your interest in space sciences come from and what led you to combine it with poetry?I think I was into space before I knew anything about the science behind and around it. When I was a little boy I used to lie on my back on the huge unlit playing field in front of my house in Huddersfield and marvel at the night sky, the Milky Way (which was very visible on the darkest, clearest nights), the bright planets and the satellites (which I hoped were alien spaceships). I also spent hours in the library pawing over books on cosmology and astronomy. I just loved the beauty of it all and the unidentifiable yearning it provoked: a yearning to explore, to disappear, to change my life, to be abducted into the infinite.

As I grew older I learned more about physics, astronomy and space exploration but by then I was so immersed in art and literature that I neglected the more scientific path I might have taken. I must admit though, that while my physics was strong, my maths began to fail me around the age of 15 or so and that nudged me towards literature and history and creative writing.

How did you become involved with the Mullard Space Science Laboratory?As with many good things, it happened almost by chance. I took part in an event with Marek Kukula (our wonderful Public Astronomer) called ‘Notes from the Universe’ at the South Bank in early 2013. I was talking about a sequence of ‘micro-poems’ I had written for Arc Magazine called ‘From Big Bang to Heat Death’, and also presenting work from my then-current book project ‘Sunspots’. Marek is very keen on bringing art and literature and science together and while we were chatting I asked him if he knew any solar physicists I could speak to about ‘Sunspots’. He suggested Dr. (now Professor) Lucie Green, who presented ‘The Sky at Night’ for several years. Lucie studies the Sun and our shared obsession meant led to some enthusiastic emails and phone call and we eventually met at her place of work, UCL’s Mullard Space Science Lab out in the green Surrey Hills.

My initial aim in all this was to augment my Sun research with the help of the Solar Group at the lab but I found the whole place so quirky, rich, diverse, and fascinating that I started thinking about doing something more inclusive and outgoing than simply working on my own book. So I began chatting to Lucie about some kind of ‘writer in residence’ role for myself, in which I would write about the laboratory and its inhabitants but, more importantly, I would try to generate new work and new forms of communication between the staff and students of the lab and its many different departments. We were lucky enough to receive a small grant from the Science and Technology Facilities Council, and I took up the role in January 2014.

What was the most surprising part of the residency for you?Deer jumping into the path of the car that drove me through the narrow winding lanes to the lab. Less viscerally, I was surprised by how many people took time out from their incredibly busy and fascinating jobs to read, write, discuss and enjoy poetry with me every couple of weeks. I was also pleasantly surprised that they were willing to do the strange things I asked them to: like automatic writing, reading Beckett plays in the blazing Sun and recording a site-specific poem in a cramped, resonant observatory. I wasn’t surprised that our discussions were so thoughtful and entertaining or that the work people produced was of such high quality.

Give us your favourite space fact from your time at the laboratory.Something I hadn’t thought about was how, when a spacecraft is designed, tested and prepared for flight, two of them are made but only one sent on its mission. The remaining craft is used for further testing and comparison should the space-bound version encounter problems. Matt Hill, a PhD student working on cryogenic physics, wrote a gently poignant poem called ‘Flight Spare’ about this less favoured also-ran.

What was the idea behind mixing the work of poets with space science interests and researchers comparatively new to poetry?The ‘official’ idea was to explore new ways for the members of the lab to communicate, work together, step out of possible ‘silos’, and play with new ways of thinking and writing. I also wanted the lab to become a little more ‘conscious’ of itself and also to find a new way for the facility to engage the public. At our ‘Sun and Moon’ event with Liane Strauss, many local fans of astronomy and literature came up to the common room for poetry, films, wine and nibbles. It was the first time that some of the scientists had read their creative writing in public. The ‘unofficial’ idea was to do something a little different and enjoy ourselves.

So what’s with the silverfish on the cover?A few weeks into my residency we discovered an infestation of silverfish in the library, assiduously devouring a century’s worth of astronomical research right under our noses. This led to many discussions about knowledge, data, ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ intelligences and how, if we had to, we might recoup vital scientific knowledge from the innards of silverfish. Also, silverfish are such intricate, beautiful creatures that took billions of years to get here: through a certain lens they looked to us like alien beings or exquisite spacecraft. The anthology is dedicated for spaceships and silverfish, which I find quite moving and very apt.

Why do you think there is such a tendency to segregate artistic and scientific practice, culturally, and to categorise people as left-brained or right-brained?I think we have a great need, perhaps an ancient need, to make quick decisions, sweep away nuance, and act. For this reason, binaries are very attractive: go one way or the other; get out of trouble quickly; choose ‘yes’ or ‘no’; don’t look back, don’t regret (if you can avoid it). We love to put things in neat boxes, to categorise each other, and to lay arguments to rest. You see it all the time in current obsessions with personality charts; right-brain/left-brain surveys; which Star Wars character are you?; are you on the left or right of the party? and so on. Digital technologies and the very means by which we communicate today are grounded on ones and zeros. Only this morning I read an interesting piece by Jonathon Coe about humour in which he writes, “The internet seems to be making our brains more binary, reducing everything to the polarised options of “Like” or “Dislike”, thereby thwarting the human impulse to entertain two contradictory responses at the same time, which seems to be one of the cornerstones of humour”

Such binaries tend to fall apart when you get to interact with people up-close, of course, although their traces have an impact. Modern education has a way of dividing and channeling people down the two classic cultural pathways of Science and Humanities, and with those paths come all kinds of assumptions, anxieties, and unfortunate blockages to certain types of knowledge. My masters degree was in Critical Theory, which in many ways was grounded in an attempt to bring the humanities and science together (think Levi-Strauss, structuralism, poststructuralism, Lacan’s unconvincing flirtation with maths and scientific formulae). Although a certain amount of this was, at least to my mind, tortuous sophistry, I suppose I was always open to bringing these different approaches to culture together.

Part of the whole point of ‘Laboratorio’ was to merge and blend the worlds of space science, engineering, scientific writing, creative writing, performance and interpretation. While there was a certain amount of fear on both ‘sides’ during my year at the lab, the results are a resounding testament to how all these fields and dichotomies can intermingle. Although I now feel even worse about my limited maths than ever. A good question that needs much more space than this to discuss.

Describe the appeal of Laboratorio to someone new to poetry and someone new to planetary science.I would say to both parties: dive into this beautifully produced book for fun and challenging tales about ‘the multiverse’; read beautiful meditations upon what an ‘observatory’ is for; explore the poignant connections between the space lab and its Iron Age foremothers; get to know Aimee Norton, a brilliant guest-poet and astronomer from Stanford University; feast on a couple of Liane Strauss’s juicy Moon poems; read a tribute to Rik Mayall; and have fun with the plucky Rosetta probe. There’s a lot more going on in this generous anthology, and it has beautiful photos of the lab too! To quote the blurb: “Laboratorio revels in the poetry of science and the science of poetry.”

What advice would you have for other artists interested in doing a residency with scientists?Be open, inclusive, enthusiastic, supportive and open to new ideas. And always have a trick or two, or a tricky exercise, in your back pocket. Also, make sure you accommodate those who may prefer quiet or solitary work to the more extrovert, group-based approach. But don’t worry about reaching everybody: some will appreciate your work silently and some won’t even realise you’re there! And do check out the STFC for possible funding. Without them, we couldn’t have made ‘Laboratorio’ happen.

Finally, tell us about the event at the Greenwich Royal Observatory!On Thursday November 12 we are officially launching the anthology at the fantastic Peter Harrison Planetarium at Greenwich. Marek Kukula will chair a discussion between myself, Lucie Greene, Julia Gaudelli and Matt Hills and there will be short readings and visuals to boot. I launched

Sunspots at the Planetarium and it’s a wonderful venue for mixing art and science in a dramatic setting.

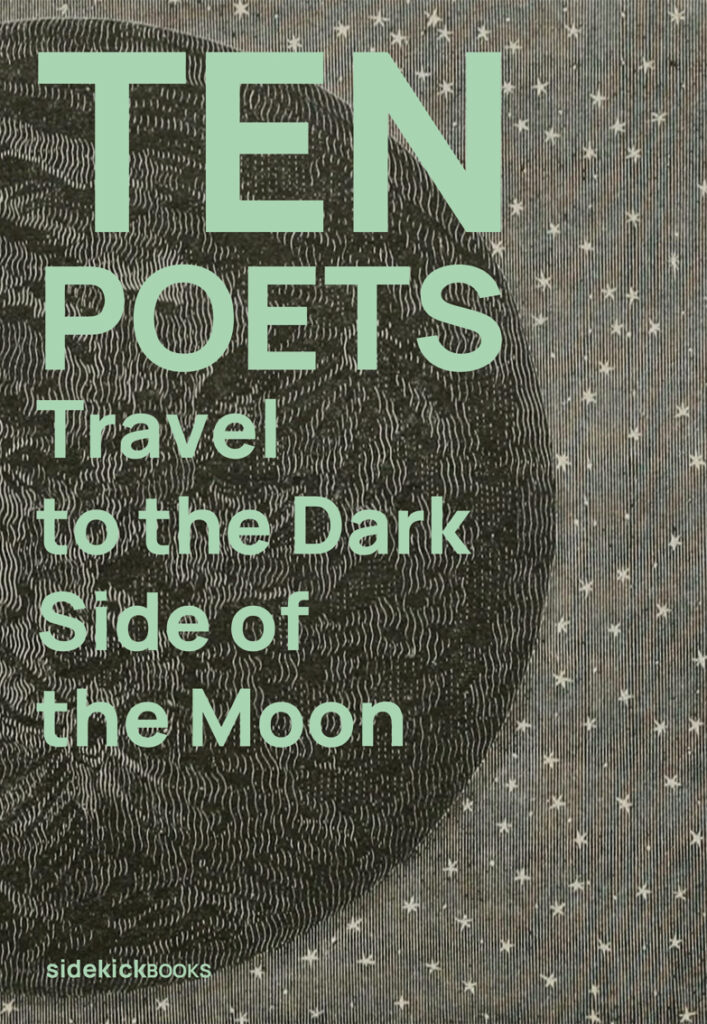

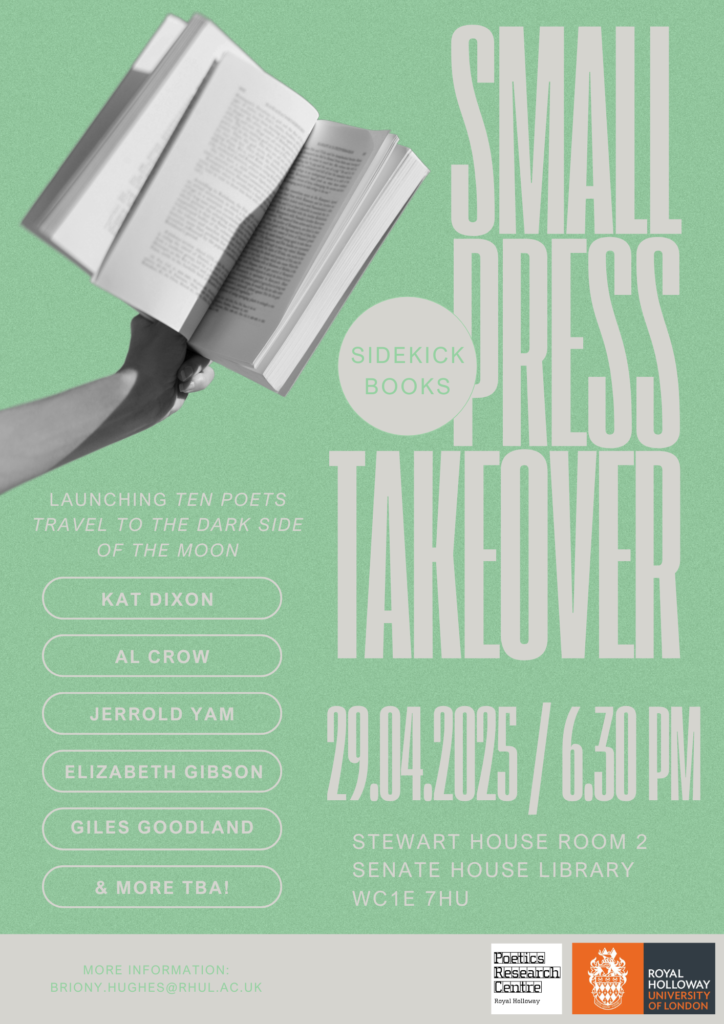

We’re joining the wonderful Dr Briony Hughes to take part in Royal Holloway’s Small Press Takeover series. There’ll be readings, a Q&A and many, many Moons!

We’re joining the wonderful Dr Briony Hughes to take part in Royal Holloway’s Small Press Takeover series. There’ll be readings, a Q&A and many, many Moons!

Look forward to seeing you, on earth or in outer space!

Look forward to seeing you, on earth or in outer space!  The incomparable

The incomparable  We’ll be starting at 7pm sharp, and the hour will include readings and short talks from Battalion contributors L. Kiew, Mike Weston, SJ Fowler, Julia Lewis, James Coghill and Cliff Hammett. Your hosts will be your devoted editors, Kirsten and Jon.

We’ll be starting at 7pm sharp, and the hour will include readings and short talks from Battalion contributors L. Kiew, Mike Weston, SJ Fowler, Julia Lewis, James Coghill and Cliff Hammett. Your hosts will be your devoted editors, Kirsten and Jon.

Expect party bags, micro-games and exercises themed around bats and poetry about these enchanting flying mammals.

Expect party bags, micro-games and exercises themed around bats and poetry about these enchanting flying mammals.

Tickets are £5, which includes a glass of mulled wine and access to all of the other events going on that evening at the reserve. You can explore the space and take a peaceful moonlight turn around the centre. You’ll also be supporting a wonderful project to protect wildlife in the heart of London.

Tickets are £5, which includes a glass of mulled wine and access to all of the other events going on that evening at the reserve. You can explore the space and take a peaceful moonlight turn around the centre. You’ll also be supporting a wonderful project to protect wildlife in the heart of London.