|

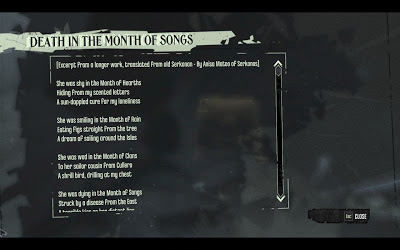

| Open mic poetry night in Grim Fandango |

This article asks, and attempts to answer, three questions:

1. What can poetry do for gaming?

Electronic gaming culture is expansive and continues to expand, with indie development in particular burgeoning at a phenomenal rate. It’s become almost an umbrella term, in that it covers everything from teenagers playing mass-marketed war simulators with film-quality CGI to commuters idly thumbing through Temple Run on the train to work, to the activist inclinations of the interactive fiction community. Many game-making tools are now freely available on the Internet, and it seems as if every few months a new lone gunman developer surfaces with a breakout hit, earning him enough to quit his job.

But the conversation around gaming comes back repeatedly to its legitimacy as an artform, with gamers frequently expressing their desire for the best games to be ‘recognised’ as works of art. What is missed in the deployment of the term ‘recognition’ is the fact that the behaviour of the audience is an immeasurably large part of what defines a practice as an art, and the principle obstacle to games being recognised as art is gamers. I don’t mean that pejoratively, but as long as the bulk of the audience for games continue to express themselves mostly through financial behaviour – buying, then exhausting the product before moving on to the next purchase – gaming will struggle not to be regarded as a form of disposable entertainment. Shakespeare is not held aloft as an artistic genius because hundreds of Elizabethans and Jacobeans flocked to see his plays night after night; his esteem has been managed and sustained by generation after generation of writers and scholars who have provided intelligent assessment and insight into his work and used it as the foundation for creative works of their own.

There is no sense, therefore, in waiting around for ‘recognition’, or indeed for waiting for the Shakespeare of the game development world. How we act and think now will change how other people think about games, and aside from financial behaviour, the vast majority of discourse is journalistic in character. I have read many, many insightful articles about games, but journalistic copy is written to be succeeded the next day by something else – it is incredibly impermanent. Games studies courses are beginning to find a foothold in academia, but academia is, by its nature, secluded and self-insulating. I don’t want to diminish the importance of either of these areas, but there needs to be as much variety in writing about games as there is in games themselves. (I would go further and suggest that the cause of gaming as art has a serious problem when the most vexed and visible conversation of recent months has been a pitched battle between affluent consumers and corporate spokespeople.)

|

| 1997’s Snake, now a thing of nostalgia, is revisited by Cliff Hammett in Coin Opera 2 |

For games and gaming to be acknowledged and discussed in poetry – in the work, that is, of writers who are, first and foremost, poets – is an important step in the way gaming is written about. It’s not quite the same thing as blending poetry into games or making poems more like games, though I’m an advocate of those as well. It’s also not simply a case of putting a badge on games, saying, “You have been deemed worthy.” Poetry has that reputation of being lofty, but has also, of course, had a sideline in reconstituting detritus into art for the better part of century, so to be plundered for poetic content is not necessarily an honouring process.

No; the importance of poetry about games, as with poetry about anything, is that it suggests new ways of considering the subject, new ways of ‘reading’ games beyond the purely evaluative. It’s a creative-critical approach. I’ve been proffering examples from Coin Opera 2 to people for some time now, so here’s just a couple more: Cliff Hammett’s ‘Snake’ works as a reading of the once-popular mobile game Snake as a visual metaphor for the movement of water across the fissures in man-made structures. It suggests this both through its words and through its shape, and might cause us to return to the original game (now long since superseded as casual entertainment by Angry Birds and its sequels) and find something new and remarkable about it. Prompting the return is important; individual games may sell millions and enjoy a brief period in the public consciousness, but if any are to rise above the level of a fad, we need to find reasons to return to them once newer ones with better graphics supplant them.

My second example is Dan Simpson’s ‘Sympathy for the Orange Ghost’, an extract from a full-length show he’s taking to the Edinburgh festival this year. Pacman is already legendary, the main character already an icon. The game has gone about as far as games can go in embedding itself in our culture. Notably, it has already had a starring role in a one-man poetry performance show: Ross Sutherland’s The Three Stigmata of Pacman. But Dan’s work enriches Pacman further by unearthing a further implied narrative in it: the outcast status of Clyde, the orange ghost, whom he lyricises into a symbol of social marginalisation in general.

Poetry about games extends their life and extends their relevance. It is, in itself, a form of the ‘recognition’ that some gamers crave, but operates through an active creative engagement. This is what poetry can do for games.

|

| Ross Sutherland performing The Three Stigmata of Pacman |

2. What can gaming do for poetry?

At first blush, the answer seems obvious. In commercial terms, poetry is a dust mite to the gaming industry’s behemoth. In fact, poetry barely even registers as an industry at all, and therefore by infiltrating the culture of gaming, poets might be seen as making some calculated grab at the larger audience.

But it’s a mistake to think in these terms. Poetry is a much wider, older and potentially longer-lasting cultural discipline than gaming, and while it might look sickly in terms of revenue, its health in terms of the number and variety of its practitioners is booming. Money troubles may slow it down, greatly reduce its reach and hurt individual poets and publishers, but poetry will go on in some form, while the unsustainability of Western opulence may still spell an early end for gaming (in its electronic form at least).

What’s more, poetry’s lack of commerciality is in large part down to its effectiveness. That is to say, a little goes a very long way. Consumers burn through games, novels and even sprawling television sagas in days and find themselves hungry for more, while a small amount of poetry is enough for most people for most of their lives. Contemporary poets struggle for attention not through lack of skill or personality, but because poets of past eras successfully remain instilled in the national psyche, nourishing our cultural discourse far beyond their lifespan. We have an excess of good poetry, and in this sense, one sensible argument is that poetry requires nothing, that it is already the survival specialist of the arts, able to live on water and thin air if need be, growing fat in times of plenty or austerity.

What poetry does crave is renewal. Without renewal, entire generations risk coming across as nothing more than an aftershock of those that came before. Renewal is the sign that poets are in step with the present and prepared to attend to it, rising to the challenge of being the world’s ‘unacknowledged legislators’, rather than wallowing in nostalgia or trying to relive past glories.

Gaming provides an obvious opportunity for such renewal. I don’t suggest, of course, that all serious poets should at once turn to games in order to demonstrate an affinity with modern life. Done cynically, this leads to cheap and embarrassing poems (see Wendy Cope’s attempts at text message poetry). But we’re now living in a world where younger people are reading more from computer screens than they are from printed material, and part of the reason for this is the richness of virtual environments, where identity is more fluid and the ways of absorbing information more varied. The opportunities for philosophical and artistic exploration are immense. Thinking, for instance, of identity – a huge preoccupation in contemporary poetry – poets should be interested in the implications of being able to come home from work and role-play as a humanoid plant who can summon the dead until bedtime. Since experience is subjective, is there any reason to believe experiences in virtual environments are less real, less a part of our make-up and a contributing factor to our character, than experiences in the concrete world? Consider this particularly in the light of the increasing amount of social interaction within online communities.

What about how virtual architecture can inform form and rhythm? It’s no coincidence, I would say, that a good number of the poems we took for Coin Opera 2 chose to use shape, space or meter as a way of expressing their engagement with a game. And because the history of game narratives is one of constant, rapid evolution and faltering experiments, often with the reins of authorial control loosened in order to accommodate player interaction, they are, I would suggest, a treasure trove of myth, where ‘myth’ means the opportunity to take elements of a known tale and retell or reinterpret them to explore wider themes.

Games are abundant, often scrambled packages of meaning waiting to be untangled and made sense of. Gaming culture is a cluster of new experiences whose careful evaluation, in any literary form, will help us all make sense of ourselves. That’s what gaming can do for poetry.

3. What else can they do for each other?

Finally, there’s the importance of cross-disciplinary discourse, which I also allude to in my Dr Fulminare interview over at Sabotage. At present, as far as I can make out, there is very little discussion between gaming and literary audiences, much within the bubble of each. Meanwhile, there are multiple issues afflicting both literary and gaming culture wherein both could benefit from sharing their ideas. One example is the problem of gender bias, which I go into more thoroughly here.

There are numerous social and political problems all of us are grappling with in some form or another. There are arguments that poetry can be a constructive force in this respect, and there are arguments that games can be a constructive force in this respect. I believe these arguments, but if they’re right, then both cultures – and both disciplines – could stand to share their ideas a little more freely.