Richard Dawkins is one of the most important and influential modern critics of religion. Most of us are familiar, even if indirectly, with his arguments in books such as The Blind Watchmaker and The God Delusion, and we know or have heard of the controversy that they generated. Dawkins derives much of his resonance from his status as a prominent scientist, rather than from his (not always original) arguments, and this is something that sets him apart from more ‘journalistic’ British atheists like the late Christopher Hitchens. It also sets him up as a natural rival to religious epistemologists, as science is frequently placed in a diametrical relation with religion: the two disciplines may be seen as incompatible and conflicting, or, more diplomatically, as two different ends of a spectrum, concerned with two different branches of knowledge. From the pope’s vocal insistence on bioethics to Einstein’s and Hawking’s famous aphorisms on God, the anecdotal literature surrounding this binary system abounds.

But there is another dualistic opposition in our culture that places science at one end and a specific discipline at the other. This is the slightly vaguer opposition of science and art. We find it encapsulated in the more general dichotomy that is manifest in our education system, that of the sciences versus the humanities. A student is normally expected to orient him/herself in the direction of one of these two, with a number of congruent modules in either of the fields. Furthermore the figure of a great artist, along with that of a great scientist, is presented to us from early childhood as pretty much the purest and noblest aspiration available in this world (not necessarily to the point that we are encouraged to become one, but at the least we are taught to admire them). More importantly, they are the only two models which subsist in a dichotomous relation. No similar bridges are raised between, say, the aspirational figure of a great athlete and that of a great businessman, or that of a great statesman and a great engineer (though these are themselves celebrated). The artist and the scientist seem intuitively related, as though linked by a thread which simultaneously aligns and opposes them to each other.

This commonality between art and religion as cultural ‘others’ to science also points to a commonality in their perceived social role. As disciplines, it is obvious that art and religion are two very different things. However, our culture has developed a way of talking about them – a unified set of clichés, myths and rhetorical figures – which are at heart identical for both. What exactly is the nature of this similarity, why does it persist, and what should be done about it?

Let us begin by exploring the first question. What are the common traits between artistic and religious discourse? What is the (linguistic) emblem that describes both of them? Or, more simply, what are we talking about, traditionally, when we say either ‘art’ or ‘religion’?

To begin with, we are talking about something that is specially recognized for its preciousness; the word we use for religion tends to be ‘holy’, whereas the word we normally use for art is ‘priceless’ (both terms have a similar function – they ban any discursive element with commercial connotations). Economic considerations do not come into it and are in fact considered vile. The real man or woman who follows or engages with this discipline is always expected to think nothing of money, but rather to be wholly dedicated to the object of his / her endeavour. This is understandable, because his / her discipline is not amenable to mathematical models and has no quantifiable dimensions; rather, it defines our society’s ethical standards and helps us find the best way to live our lives, either by teaching or simply by suggesting; it explores and sometimes explains the best path(s) towards happiness, on the strict condition that we be true to ourselves (when our ‘selves’ do not correspond or agree with the work of art or with the dominant religion, this leads to conflict and paradox – as usually explored in minority discourse). As such, it is culture’s primary source of opposition to inducted values such as consumerism or materialism, acting as a stalwart against greed and superficiality. It (supposedly) trains our sensitivity and kindness as well.

Naturally this object that we are talking about is transcendental. Perhaps more significantly, it is an end in itself. Though it benefits society as a whole in a number of ways (Dawkins has contended this bit with respect to religion), it can also be done for its own sake, and indeed is primarily approached for this reason. As a self-sufficient ‘end’, and thinking on a grander scale now, it justifies the whole of humanity. It redeems it, both individually, acting on its people one by one, and also historically. A civilisation may legitimise its course and passage over the face of the earth if it leaves us with a heritage of great art or if it greatly contributes to the spreading of the Word, which is the same thing. It can also attain the same recognition if it greatly advances science – but that’s the other end of the spectrum.

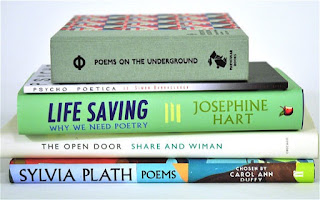

Since in both the cases of art and religion we are talking about what is essentially a discipline, it only rewards in degrees commensurate to the efforts that are put in. It is of little use if it is treated casually, or if it is only thought of in passing, once every now and then. People who handle it this way are regarded with paternal benevolence by those who take it seriously instead (but with frequent encouragements to ‘practice it’ more often, be it by coming to the prayer sessions or by reading the poems of Coleridge / Milton / Neruda…). A serious commitment to this discipline demands long hours of study, a deep acquaintance with the history and culture of your specific ‘school’, and a great deal of introspection. The implicit reward of all this is a certain happiness, of course, but also a special type of wisdom. This may loosely be referred to as ‘enlightenment’, according to its manner (and maybe suddenness) of acquisition. Emphatically, depending on the subject, we may even talk of salvation.

The general conception is this – that though the reward of the discipline is available to everyone, for it is not precluded by class, sex or race, in practice only a handful of people actually attain it. The hierarchy of success, here, is aristocratic: it is defined by a special gift known as ‘talent’ in art and as ‘piety’ in religion (the importance of piety has greatly declined since the times of the legendary saints, but so has proactive religious discourse in general – more on this later). Societies go to great lengths to celebrate individuals with this special gift, and very many of our legends are woven specifically around these people (the only discourse which compares to the spiritual one for mythopoeic power, in fact, is that of war). Therefore in this discipline we find prophets and martyrs, people who see ahead of their time and reveal to us the real nature of things, sending out messages which are then misunderstood or fearfully rejected, or people who die for their commitment to their private cause, thereby becoming instant icons, worshipped past all others, even to the point of eclipsing the real value of their work. After all, they demonstrate the transcendental value of the discipline that they upheld; for is it not worth dying for? Is it not larger than life? And is not one of the greatest tropes in this discourse precisely the separation between ‘art and life’, or between the concerns of ‘after-life and life’?

The myth of the saint, which has an extensive history from the Roman Christian era to well past the middle-ages, is re-elaborated in our present age as the myth of the artist, that precociously illuminated, infinitely sensitive, candid introvert, divorced from ordinary people by virtue of the very talents that elevate him / her above the world. This character is at the heart of such works as James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man or Thomas Mann’s Tonio Kroger. Baudelaire sums up the character in the famous ending to his poem The Albatross:

But there is another dualistic opposition in our culture that places science at one end and a specific discipline at the other. This is the slightly vaguer opposition of science and art. We find it encapsulated in the more general dichotomy that is manifest in our education system, that of the sciences versus the humanities. A student is normally expected to orient him/herself in the direction of one of these two, with a number of congruent modules in either of the fields. Furthermore the figure of a great artist, along with that of a great scientist, is presented to us from early childhood as pretty much the purest and noblest aspiration available in this world (not necessarily to the point that we are encouraged to become one, but at the least we are taught to admire them). More importantly, they are the only two models which subsist in a dichotomous relation. No similar bridges are raised between, say, the aspirational figure of a great athlete and that of a great businessman, or that of a great statesman and a great engineer (though these are themselves celebrated). The artist and the scientist seem intuitively related, as though linked by a thread which simultaneously aligns and opposes them to each other.

This commonality between art and religion as cultural ‘others’ to science also points to a commonality in their perceived social role. As disciplines, it is obvious that art and religion are two very different things. However, our culture has developed a way of talking about them – a unified set of clichés, myths and rhetorical figures – which are at heart identical for both. What exactly is the nature of this similarity, why does it persist, and what should be done about it?

Let us begin by exploring the first question. What are the common traits between artistic and religious discourse? What is the (linguistic) emblem that describes both of them? Or, more simply, what are we talking about, traditionally, when we say either ‘art’ or ‘religion’?

To begin with, we are talking about something that is specially recognized for its preciousness; the word we use for religion tends to be ‘holy’, whereas the word we normally use for art is ‘priceless’ (both terms have a similar function – they ban any discursive element with commercial connotations). Economic considerations do not come into it and are in fact considered vile. The real man or woman who follows or engages with this discipline is always expected to think nothing of money, but rather to be wholly dedicated to the object of his / her endeavour. This is understandable, because his / her discipline is not amenable to mathematical models and has no quantifiable dimensions; rather, it defines our society’s ethical standards and helps us find the best way to live our lives, either by teaching or simply by suggesting; it explores and sometimes explains the best path(s) towards happiness, on the strict condition that we be true to ourselves (when our ‘selves’ do not correspond or agree with the work of art or with the dominant religion, this leads to conflict and paradox – as usually explored in minority discourse). As such, it is culture’s primary source of opposition to inducted values such as consumerism or materialism, acting as a stalwart against greed and superficiality. It (supposedly) trains our sensitivity and kindness as well.

Naturally this object that we are talking about is transcendental. Perhaps more significantly, it is an end in itself. Though it benefits society as a whole in a number of ways (Dawkins has contended this bit with respect to religion), it can also be done for its own sake, and indeed is primarily approached for this reason. As a self-sufficient ‘end’, and thinking on a grander scale now, it justifies the whole of humanity. It redeems it, both individually, acting on its people one by one, and also historically. A civilisation may legitimise its course and passage over the face of the earth if it leaves us with a heritage of great art or if it greatly contributes to the spreading of the Word, which is the same thing. It can also attain the same recognition if it greatly advances science – but that’s the other end of the spectrum.

Since in both the cases of art and religion we are talking about what is essentially a discipline, it only rewards in degrees commensurate to the efforts that are put in. It is of little use if it is treated casually, or if it is only thought of in passing, once every now and then. People who handle it this way are regarded with paternal benevolence by those who take it seriously instead (but with frequent encouragements to ‘practice it’ more often, be it by coming to the prayer sessions or by reading the poems of Coleridge / Milton / Neruda…). A serious commitment to this discipline demands long hours of study, a deep acquaintance with the history and culture of your specific ‘school’, and a great deal of introspection. The implicit reward of all this is a certain happiness, of course, but also a special type of wisdom. This may loosely be referred to as ‘enlightenment’, according to its manner (and maybe suddenness) of acquisition. Emphatically, depending on the subject, we may even talk of salvation.

The general conception is this – that though the reward of the discipline is available to everyone, for it is not precluded by class, sex or race, in practice only a handful of people actually attain it. The hierarchy of success, here, is aristocratic: it is defined by a special gift known as ‘talent’ in art and as ‘piety’ in religion (the importance of piety has greatly declined since the times of the legendary saints, but so has proactive religious discourse in general – more on this later). Societies go to great lengths to celebrate individuals with this special gift, and very many of our legends are woven specifically around these people (the only discourse which compares to the spiritual one for mythopoeic power, in fact, is that of war). Therefore in this discipline we find prophets and martyrs, people who see ahead of their time and reveal to us the real nature of things, sending out messages which are then misunderstood or fearfully rejected, or people who die for their commitment to their private cause, thereby becoming instant icons, worshipped past all others, even to the point of eclipsing the real value of their work. After all, they demonstrate the transcendental value of the discipline that they upheld; for is it not worth dying for? Is it not larger than life? And is not one of the greatest tropes in this discourse precisely the separation between ‘art and life’, or between the concerns of ‘after-life and life’?

The myth of the saint, which has an extensive history from the Roman Christian era to well past the middle-ages, is re-elaborated in our present age as the myth of the artist, that precociously illuminated, infinitely sensitive, candid introvert, divorced from ordinary people by virtue of the very talents that elevate him / her above the world. This character is at the heart of such works as James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man or Thomas Mann’s Tonio Kroger. Baudelaire sums up the character in the famous ending to his poem The Albatross:

The Poet is his kinsman in the clouds

Who scoffs at archers, loves a stormy day;

But on the ground, among the hooting crowds,

He cannot walk, his wings are in the way.

A step below the ‘chosen ones’, the saints and great artists, the discipline then includes a whole set of subordinates whose role is to mediate and explain: religion has priests, and art has academics and / or critics. This without mentioning the legions of novices, in schools both improvised and recognised.

Keep reading in Part Two…

Keep reading in Part Two…