While we might wonder at the seeming arbitrariness of judgements in poetry competitions, the lure of winning still ensures a healthy number of entries. Upwards of 30 poetry prizes are currently active in the UK alone and in recent years publishers have begun to host competitions for whole manuscripts, the winners of which receive publication with the press and often a few hundred pounds to boot. The money for the richest poetry competitions may still be far lower than that for prose and factual writing but any cash prize is attractive, particularly for such a poorly funded artform.

And the money is simply the start. Should you be fortunate enough to win the UK’s National Poetry Competition, the initial effect must feel not unlike being plucked from the poetry workhouse and given a shot at becoming a gentleman. Furthermore, when entering such competitions, which are necessarily pay-to-play, you are also reminded that in doing so you are supporting the organisers and UK poetry as a while, so even if you don’t win, you can console yourself with the fact that you are supporting your artform. Everybody wins, right?

Not exactly. We can stake too much on the life-changing ‘lucky strike’, just as we can fall for the myth that Being Published will automatically mean everybody stops to notice our brilliance. The one-win-solves-all idea is very seductive, but the associated cycle of hope and disappointment can be very damaging to one’s self-esteem and capacity for courage. Worse yet, focusing too much on the gold medal can cause us to make unwise, desperate moves that ultimately harm us.

I wasn’t published as the result of winning a competition (that came about as a big surprise during the manuscript-mulling period), but partly because I co-ran Fuselit, which led to being invited to read when I moved to London, which led to discovering and supporting the work of others, which eventually led to my now-editor, who was the first person to give me a shot on stage, commissioning my book for Salt. Now that the book is a reality it’s amazing but it’s hardly been a question of “You’ve made it. Stop here and collect acclaim.”

The alternative is to do as many excellent writers do, and throw ourselves into improving and experimenting. It’s a slower process, but it pays more satisfying and sustainable dividends. Such writers produce work with tremendous character, which influences others along the way. Many have never won a prize or placed in a major competition and nobody cares one iota.

Competitions can be a very positive thing. They do raise needed funds and provide opportunities, particularly for those writers who don’t have access to London’s bustling poetry scene. But for each contest, there are a tiny number of winners, and often only one of these winners receives a financial prize. And unless you garner a whole raft of accolades at once, that glow can fade surprisingly quickly (how many past NPC winners can you name without looking them up?).

Rather than simply reiterating the statistical unlikelihood of winning in the first place, perhaps we should simply remember that prizes guarantee nothing. There are plenty of paths to success outside the awards circuit, and any endeavour which celebrates more than one person, more than once a year, and which carries as a reward something more than a single deal or clot of money, surely offers the best odds for success.

Some martial arts schools treat the gaining of grades not as a mark of achievement but as a test. Once you have been given the belt or grade, it’s up to you to work out how best to continue training and developing. Instead of thinking, “Awesome. Now I’m going to write another book”, it would be good to see more victors follow the example of one group of Foyle Young Poets and say, “Awesome. Now let’s start a magazine.”

Author: Kirsten Irving

Farzaneh Khojandi, and the English / Persian poetry relation

In November of 2012, we published a negative review of the pamphlet ‘Poems’ by Persian author Farzaneh Khojandi, which ended with a call for elucidations. This is the first article we have received in response, written for us by Maryam Fathollahi. The editors would like to thank her for her time and effort.

Can Persian poems be understood with effortless ease, and are their pleasures immediately accessible? They can and are with due time, but one must familiarise oneself with the culture, and mature works should be picked as a starting point. Let us discuss the issue with respect to the work of Khojandi, a contemporary poet from Tajikistan.

When I first finished the draft for this article, I forwarded it to a knowledgeable expert to have his opinion. After reading the paper, he told me “your article is full of Persian metaphors and beautiful figures of Persian speech, but translating it into fluent English would be a difficult, complicated matter. An article needs transparent and tangible words.” Our discussion on this subject encouraged me to research several aspects concerning poetry translation. First of all, it became apparent to me that poetry translators should have a strong understanding of the view, the emotion, and the culture of their readers. In addition to this, they should of course adhere to the original concepts presented in the source text and indeed they should try to reproduce the poetic form. Poetry translation is therefore much more challenging than the translation of ordinary texts.

Farzaneh Khojandi is a poet from Tajikistan; her last name derives from the name of her birthplace, Khojand. She has published several poetry books and is nowadays considered the head of poets in Tajikistan, primarily owing to her lyric poems; it is through these poems that she came to be known as “the Forough of Tajikistan”.

“Forough of Tajikistan” may refer to two distinct meanings. Firstly, “Forough” is a Persian word meaning brilliance, brightness, light and shining. It therefore signifies that Farzaneh Khojandi is like a sun shining over the literature of Tajikistan. On the other hand “Forough” reminds me of a female intellectual and prominent Iranian poet, Forough Farrokhzad, sometimes called “the Forough” in Iran.

Will Farzaneh Khojandi of Tajikistan become another Forough Farrokhzad? Will her works find a wide readership? Before tackling these questions, let us provide a brief overview on the relationship between the Persian and English languages.

In the late eighteenth-century Sir William Jones (Youns Uksfardi) noticed the existence of a close relation between certain Indo-European languages. In fact, some other scholars before Jones had already noticed that a family of languages (namely German, English, Persian, and others) share the same root. But how did they develop into their differences? I believe the primary reason has to do with their cultural evolution, relative to their individual nations. A good example of this is the interaction of culture for people who live in Iran and Tajikistan. However, Farsi is a principal joint.

Furthermore, the nineteenth-century saw the beginning of serious inspections of language. Studies of researchers show that language is a social intuition continuously altering. Given this premise, it follows that translation is a correspondently dynamic process. I tend to think that translation must import culture by conveying its concepts, but on the other hand, it will also deform the source poetry. As a result, it will mean a loss of the poetry’s original aesthetic vision.

It seems to me we need more to know about the process of translation behind Khojandi’s poems. Have the translators conveyed the meaning of her poetry under her judgement?! And have they thought of her English readers? It is necessary to hear her opinion on the matter because Iran is a land of civilization and great poets. In a not-so-distant past, many neighbouring countries of Iran – such as Tajikistan – were provinces of modern Iran. Farsi was thus the common language between them. Poets such as Rudaki, Khayyam, Ferdowsi, Rumi, Hafez and Saadi, as well as contemporary poets such as Nima Yooshij, Ahmad Shamloo, Forough Farrokhzad, Sohrab Sepehri are Iranians who have written Farsi poetry.

Of course, Farsi poetry consists of a variety of figures of speech. These include: rhyme, metaphor, imagery symbolism, oxymoron, synaesthesia, personification, ambiguity, defamiliarisation and others. Through these, Persian poetry works like a painting or a film to allow readers to evince a lofty ideal from it. To be more precise, figures of Persian speech are the best aesthetic aspect of Persian poetry. And yet a correct translation of Persian poetry must be familiar with the culture and the background behind the use of certain words (in Farsi).

In the final analysis, although English is already an international language, we require an organization or an institution to include all of the world’s poets and translators in an effort to improve the process of translation. Moreover, it would be a good idea to produce an encyclopedia (by these very poets and translators) in order to simplify translation and decipher figures of speech with respect to the cultural diversity of their lands of origin. Therefore, there needs to be an endless communication with poets and translators of the world to start new studies and to better understand poetry from all countries, including the beauty of Persian poetry.

Maryam Fathollahi was born in 1982 in Tehran (capital of Iran). She has a BA and is currently studying French translation. She started writing poetry in 1997 and has won local competitions in Persian poetry in 2001 and 2005, in Tehran. Her first Persian poetry book was published in 2008, under the title The Beautiful Mares. She is also the author of a script that she completed in 2012. She is currently writing a novel and is editing her second Farsi collection, entitled The Expectation.

Can Persian poems be understood with effortless ease, and are their pleasures immediately accessible? They can and are with due time, but one must familiarise oneself with the culture, and mature works should be picked as a starting point. Let us discuss the issue with respect to the work of Khojandi, a contemporary poet from Tajikistan.

When I first finished the draft for this article, I forwarded it to a knowledgeable expert to have his opinion. After reading the paper, he told me “your article is full of Persian metaphors and beautiful figures of Persian speech, but translating it into fluent English would be a difficult, complicated matter. An article needs transparent and tangible words.” Our discussion on this subject encouraged me to research several aspects concerning poetry translation. First of all, it became apparent to me that poetry translators should have a strong understanding of the view, the emotion, and the culture of their readers. In addition to this, they should of course adhere to the original concepts presented in the source text and indeed they should try to reproduce the poetic form. Poetry translation is therefore much more challenging than the translation of ordinary texts.

Farzaneh Khojandi is a poet from Tajikistan; her last name derives from the name of her birthplace, Khojand. She has published several poetry books and is nowadays considered the head of poets in Tajikistan, primarily owing to her lyric poems; it is through these poems that she came to be known as “the Forough of Tajikistan”.

“Forough of Tajikistan” may refer to two distinct meanings. Firstly, “Forough” is a Persian word meaning brilliance, brightness, light and shining. It therefore signifies that Farzaneh Khojandi is like a sun shining over the literature of Tajikistan. On the other hand “Forough” reminds me of a female intellectual and prominent Iranian poet, Forough Farrokhzad, sometimes called “the Forough” in Iran.

Will Farzaneh Khojandi of Tajikistan become another Forough Farrokhzad? Will her works find a wide readership? Before tackling these questions, let us provide a brief overview on the relationship between the Persian and English languages.

In the late eighteenth-century Sir William Jones (Youns Uksfardi) noticed the existence of a close relation between certain Indo-European languages. In fact, some other scholars before Jones had already noticed that a family of languages (namely German, English, Persian, and others) share the same root. But how did they develop into their differences? I believe the primary reason has to do with their cultural evolution, relative to their individual nations. A good example of this is the interaction of culture for people who live in Iran and Tajikistan. However, Farsi is a principal joint.

Furthermore, the nineteenth-century saw the beginning of serious inspections of language. Studies of researchers show that language is a social intuition continuously altering. Given this premise, it follows that translation is a correspondently dynamic process. I tend to think that translation must import culture by conveying its concepts, but on the other hand, it will also deform the source poetry. As a result, it will mean a loss of the poetry’s original aesthetic vision.

It seems to me we need more to know about the process of translation behind Khojandi’s poems. Have the translators conveyed the meaning of her poetry under her judgement?! And have they thought of her English readers? It is necessary to hear her opinion on the matter because Iran is a land of civilization and great poets. In a not-so-distant past, many neighbouring countries of Iran – such as Tajikistan – were provinces of modern Iran. Farsi was thus the common language between them. Poets such as Rudaki, Khayyam, Ferdowsi, Rumi, Hafez and Saadi, as well as contemporary poets such as Nima Yooshij, Ahmad Shamloo, Forough Farrokhzad, Sohrab Sepehri are Iranians who have written Farsi poetry.

Of course, Farsi poetry consists of a variety of figures of speech. These include: rhyme, metaphor, imagery symbolism, oxymoron, synaesthesia, personification, ambiguity, defamiliarisation and others. Through these, Persian poetry works like a painting or a film to allow readers to evince a lofty ideal from it. To be more precise, figures of Persian speech are the best aesthetic aspect of Persian poetry. And yet a correct translation of Persian poetry must be familiar with the culture and the background behind the use of certain words (in Farsi).

In the final analysis, although English is already an international language, we require an organization or an institution to include all of the world’s poets and translators in an effort to improve the process of translation. Moreover, it would be a good idea to produce an encyclopedia (by these very poets and translators) in order to simplify translation and decipher figures of speech with respect to the cultural diversity of their lands of origin. Therefore, there needs to be an endless communication with poets and translators of the world to start new studies and to better understand poetry from all countries, including the beauty of Persian poetry.

Maryam Fathollahi was born in 1982 in Tehran (capital of Iran). She has a BA and is currently studying French translation. She started writing poetry in 1997 and has won local competitions in Persian poetry in 2001 and 2005, in Tehran. Her first Persian poetry book was published in 2008, under the title The Beautiful Mares. She is also the author of a script that she completed in 2012. She is currently writing a novel and is editing her second Farsi collection, entitled The Expectation.

Sunday Review: Robert Stein’s ‘The Very End of Air’

posted by the Judge

It’s my turn back at the reviewing board, and this Sunday I’m giving a twirl to Robert Stein‘s The Very End of Air. You can find the review here.

It was actually an interesting article to write. The collection itself was a mixed bag, but those aspects that I did not like were very much worth exploring, as I don’t think they are exclusive to Stein at all (not even exclusive to poetry, in fact).

Have a great Sunday, or should I say, a great Sunday night!

It’s my turn back at the reviewing board, and this Sunday I’m giving a twirl to Robert Stein‘s The Very End of Air. You can find the review here.

It was actually an interesting article to write. The collection itself was a mixed bag, but those aspects that I did not like were very much worth exploring, as I don’t think they are exclusive to Stein at all (not even exclusive to poetry, in fact).

Have a great Sunday, or should I say, a great Sunday night!

An Anatomy of the Spirit, Part 2

Part 2 of the article we started last week on the subject of spirituality, religion and art, written by the Judge.

The similarities, though extensive so far, do not end there. Our relation with the brand name of any given art or religion is always understood as a matter of profound intimacy, which brings with it an expectation that we should treat it with great respect. The typical case-scenario, with the arts, is that of an adolescent bringing you his / her poem or song or painting and asking for feedback. In all cases (and especially with poetry), responses will be subdued and hugely diplomatic. Similarly, when talking to a friend about religion, one tends to coat any criticism in layers of softening disclaimers: “I hope you’re not offended by this, but…”. This is what Dawkins protests about in The God Delusion when he claims that cooking criticism, for example, is much harsher than anything he writes in his books, yet people still get offended by his work. But this very social norm is also what produces the inevitable dissidents and demagogues, those people who brazenly remark that this great painter or that great composer is ‘crap’, or that all religion is a load of rubbish.

The diplomatic aspect of engaging in dialogue with people about the art and religion produced by their culture is delicate in precise proportion to how distant their culture is. It is especially marked when it crosses that great (and unfathomable) geopolitical divide, that of the West and the East. It is a common cliché to say that the West is less ‘spiritual’ than the East, or at least more materialistic. What this slogan fails to consider, however, is that the discourse of the arts represents precisely the West’s forum of spirituality. Most of the discursive elements we find in, say, Buddhism or Confucianism are given voice in the West by the philosophies, critiques, models, meditations, catharses staged within the world of the arts (even if the methods and the conclusions may be very different).

The trope of spirituality is helpful when trying to understand the binding thread between art and religion. The term is chosen only for convenience, and I don’t mean for it to refer to any particularly complicated concept. Spirituality, as it is expressed in our religious and artistic discourse, refers simply to the way that we relate not to what is unknown, but to what is unknowable. The positing of an epistemological trope which is always one step beyond our available methodologies is what defines the concept of the transcendental. From this point of view, religious enthusiasts are right in saying that human beings are inherently spiritual creatures. For any form of knowledge must also be a knowledge of its own limits; and it is the projection of these limits that inevitably gives a specific form to our understanding of the transcendental.

The transition from religious to artistic discourse – for the transference of spiritual qualities from the saint onto the artist should indeed be interpreted as a transition, and not as a form of decadence or progress – can only too easily be interpreted in reductionist or dismissive terms. But to say, for instance, that art is no more than religion for those who do not believe in God (an example of an easy aphorism) would be to miss the point. Art and religion belong to the same immortal myth that fuels or provides an outlet for man / woman’s spirituality and that resists even such radical cultural processes as the ‘death of God’. By the latter Nietzschean expression I am not referring simply to a decline in church attendance or in declared faith – this subject has been mined extensively, by Dawkins among others. The meaning of the original expression refers to a process that is cultural, discursive, even memetic, and not social or sociological. It implies that the idea itself of God’s existence, of what it means for God to exist, has been culturally transformed to the point of having little or no meaning at all – in this sense God is supposedly ‘dead’.

This is best exemplified, ironically, by one of Dawkins’ most successful antagonists. Terry Eagleton’s attempt to define / describe God in his famous riposte to The God Delusion is worth quoting in full:

Dawkins speaks scoffingly of a personal God, as though it were entirely obvious exactly what this might mean. He seems to imagine God, if not exactly with a white beard, then at least as some kind of chap, however supersized. He asks how this chap can speak to billions of people simultaneously, which is rather like wondering why, if Tony Blair is an octopus, he has only two arms. For Judeo-Christianity, God is not a person in the sense that Al Gore arguably is. Nor is he a principle, an entity, or ‘existent’: in one sense of that word it would be perfectly coherent for religious types to claim that God does not in fact exist. He is, rather, the condition of possibility of any entity whatsoever, including ourselves. He is the answer to why there is something rather than nothing. God and the universe do not add up to two, any more than my envy and my left foot constitute a pair of objects.

This, not some super-manufacturing, is what is traditionally meant by the claim that God is Creator. He is what sustains all things in being by his love; and this would still be the case even if the universe had no beginning. To say that he brought it into being ex nihilo is not a measure of how very clever he is, but to suggest that he did it out of love rather than need. The world was not the consequence of an inexorable chain of cause and effect. Like a Modernist work of art, there is no necessity about it at all, and God might well have come to regret his handiwork some aeons ago. The Creation is the original acte gratuit. God is an artist who did it for the sheer love or hell of it, not a scientist at work on a magnificently rational design that will impress his research grant body no end.

Inevitably, Eagleton concludes his tirade by throwing us back to the dichotomy of art and science. But what his finely articulated argument indirectly suggests is that the question of the existence of God has become a rhetorical one – intended as a question that allows for the exercise of rhetoric, and not one that actually necessitates or invokes answers. Theologians are dishonest who claim that this has always been the form of the question, as this cultural ‘death of God’ can only be traced to a few centuries ago, not so distantly separated from the rise of Romanticism and the production of a genuine mythology of the arts.

It has often been noted that Dawkins only divulgates arguments that were established for centuries among the intelligentsia, and this is why he is usually scoffed at by the academics. Yet amid the educated, very few people still believe in God in the original sense of the expression. Even the declared Christians normally reformat their faith in terms of a God which has no form or agency – God as some abstraction, as love, as the condition for things to exist, and so on. Thus, the expression ‘to believe in God’ is used as the platform or pretext for spiritual systems which subsist perfectly well without the notion of God (and which can even be informed by modern godless ideologies, like existentialism or socialism). More often than not, these spiritual systems will find expression in the arts, as they are elaborated in paintings or poems or films.

This invisible collapse (or transformation) of theocentric ideologies has been attended by the collapse of the religious mythologies which, in turn, have been replaced by those of art. The once-pervasive figure / myth of the saint, for example, is evanescent in modern-day culture. When was the last time that someone made a film about one? Compare this to the number of times that a movie is produced about some great writer / musician / painter / dancer, or about some kid aspiring to become one. There are always several titles per year.

Religious discourse itself is now reactive rather than proactive, a sure sign that its mythopoeic power has been dissipated. Its interpreters will take a stance against stem-cell research, against pre-marital sex, against abortion, against, against, against. And while there is much going on within the confines of religion itself, its activity remains nonetheless endocentric – that is to say, while discoveries in science will affect literature and developments in music will affect fashion, religious discourse affects no other discourse outside of itself – if not in repressive terms.

Artistic discourse is, however, no more adequate than traditional religious discourse as a spiritual platform. It promotes false gods in equal measure, so much so that an artistic ambition in a young person – something that is usually celebrated, cherished and admired by the surrounding adults – can actually be a symptom of psychological ill-health. Only too frequently, it can lead to attitudes of elitism and narcissism, an inability to properly develop one’s social skills (resulting from – and in – a damaging self-ostracism), and, most worryingly, a certain disinclination to engage with the social realities of one’s generation. Fortunately, these are issues that most good artists will grow out of as they mature, going to show that our spirituality is indeed something to be cultivated individually, and not imposed by doctrines or dogmas or schools – however well-meaning these may be.

Still, in fairness to artistic discourse (at least, to its vivacity and flexibility), it can be pointed out that ‘Art’ has already been questioned. In fact, postmodern artists have been questioning it for several decades, though they never really debunked it as a dominant myth. They probably won’t, at least until art as a concept becomes genuinely disassociated from spirituality. Much like war is contested by great artists from every generation, but its myth has never stopped producing endless (and sometimes wonderful) stories and books and plays and films, so the power of ‘the spirit’ as a source of inspiration remains measureless, as it is given by the primal, indispensable reality of our relationship with the transcendental. This relationship needs no more than time and sincerity to be cultivated properly, but it does exist; and an inability to understand our inherent spirituality represents the greatest failure of the New Atheists. God, for the most part, seems to have been put aside for the purposes of spiritual development. It is no stretch to say that Art could end in the same way, long before Dawkins decides to write The Art Delusion.

Sunday Review: Night Journey by Richard Lambert

The Judge is away this week, no doubt quaffing a lovely single malt on a tatami mat just south of Felixstowe or somesuch, but we’re bounding right into 2012 with the Irregular Features Sunday Review. This week Harry Giles gets going with Night Journey by Richard Lambert, published by Eyewear.

An Anatomy of the Spirit (Part 1)

written by the Judge

Richard Dawkins is one of the most important and influential modern critics of religion. Most of us are familiar, even if indirectly, with his arguments in books such as The Blind Watchmaker and The God Delusion, and we know or have heard of the controversy that they generated. Dawkins derives much of his resonance from his status as a prominent scientist, rather than from his (not always original) arguments, and this is something that sets him apart from more ‘journalistic’ British atheists like the late Christopher Hitchens. It also sets him up as a natural rival to religious epistemologists, as science is frequently placed in a diametrical relation with religion: the two disciplines may be seen as incompatible and conflicting, or, more diplomatically, as two different ends of a spectrum, concerned with two different branches of knowledge. From the pope’s vocal insistence on bioethics to Einstein’s and Hawking’s famous aphorisms on God, the anecdotal literature surrounding this binary system abounds.

But there is another dualistic opposition in our culture that places science at one end and a specific discipline at the other. This is the slightly vaguer opposition of science and art. We find it encapsulated in the more general dichotomy that is manifest in our education system, that of the sciences versus the humanities. A student is normally expected to orient him/herself in the direction of one of these two, with a number of congruent modules in either of the fields. Furthermore the figure of a great artist, along with that of a great scientist, is presented to us from early childhood as pretty much the purest and noblest aspiration available in this world (not necessarily to the point that we are encouraged to become one, but at the least we are taught to admire them). More importantly, they are the only two models which subsist in a dichotomous relation. No similar bridges are raised between, say, the aspirational figure of a great athlete and that of a great businessman, or that of a great statesman and a great engineer (though these are themselves celebrated). The artist and the scientist seem intuitively related, as though linked by a thread which simultaneously aligns and opposes them to each other.

This commonality between art and religion as cultural ‘others’ to science also points to a commonality in their perceived social role. As disciplines, it is obvious that art and religion are two very different things. However, our culture has developed a way of talking about them – a unified set of clichés, myths and rhetorical figures – which are at heart identical for both. What exactly is the nature of this similarity, why does it persist, and what should be done about it?

Let us begin by exploring the first question. What are the common traits between artistic and religious discourse? What is the (linguistic) emblem that describes both of them? Or, more simply, what are we talking about, traditionally, when we say either ‘art’ or ‘religion’?

To begin with, we are talking about something that is specially recognized for its preciousness; the word we use for religion tends to be ‘holy’, whereas the word we normally use for art is ‘priceless’ (both terms have a similar function – they ban any discursive element with commercial connotations). Economic considerations do not come into it and are in fact considered vile. The real man or woman who follows or engages with this discipline is always expected to think nothing of money, but rather to be wholly dedicated to the object of his / her endeavour. This is understandable, because his / her discipline is not amenable to mathematical models and has no quantifiable dimensions; rather, it defines our society’s ethical standards and helps us find the best way to live our lives, either by teaching or simply by suggesting; it explores and sometimes explains the best path(s) towards happiness, on the strict condition that we be true to ourselves (when our ‘selves’ do not correspond or agree with the work of art or with the dominant religion, this leads to conflict and paradox – as usually explored in minority discourse). As such, it is culture’s primary source of opposition to inducted values such as consumerism or materialism, acting as a stalwart against greed and superficiality. It (supposedly) trains our sensitivity and kindness as well.

Naturally this object that we are talking about is transcendental. Perhaps more significantly, it is an end in itself. Though it benefits society as a whole in a number of ways (Dawkins has contended this bit with respect to religion), it can also be done for its own sake, and indeed is primarily approached for this reason. As a self-sufficient ‘end’, and thinking on a grander scale now, it justifies the whole of humanity. It redeems it, both individually, acting on its people one by one, and also historically. A civilisation may legitimise its course and passage over the face of the earth if it leaves us with a heritage of great art or if it greatly contributes to the spreading of the Word, which is the same thing. It can also attain the same recognition if it greatly advances science – but that’s the other end of the spectrum.

Since in both the cases of art and religion we are talking about what is essentially a discipline, it only rewards in degrees commensurate to the efforts that are put in. It is of little use if it is treated casually, or if it is only thought of in passing, once every now and then. People who handle it this way are regarded with paternal benevolence by those who take it seriously instead (but with frequent encouragements to ‘practice it’ more often, be it by coming to the prayer sessions or by reading the poems of Coleridge / Milton / Neruda…). A serious commitment to this discipline demands long hours of study, a deep acquaintance with the history and culture of your specific ‘school’, and a great deal of introspection. The implicit reward of all this is a certain happiness, of course, but also a special type of wisdom. This may loosely be referred to as ‘enlightenment’, according to its manner (and maybe suddenness) of acquisition. Emphatically, depending on the subject, we may even talk of salvation.

The general conception is this – that though the reward of the discipline is available to everyone, for it is not precluded by class, sex or race, in practice only a handful of people actually attain it. The hierarchy of success, here, is aristocratic: it is defined by a special gift known as ‘talent’ in art and as ‘piety’ in religion (the importance of piety has greatly declined since the times of the legendary saints, but so has proactive religious discourse in general – more on this later). Societies go to great lengths to celebrate individuals with this special gift, and very many of our legends are woven specifically around these people (the only discourse which compares to the spiritual one for mythopoeic power, in fact, is that of war). Therefore in this discipline we find prophets and martyrs, people who see ahead of their time and reveal to us the real nature of things, sending out messages which are then misunderstood or fearfully rejected, or people who die for their commitment to their private cause, thereby becoming instant icons, worshipped past all others, even to the point of eclipsing the real value of their work. After all, they demonstrate the transcendental value of the discipline that they upheld; for is it not worth dying for? Is it not larger than life? And is not one of the greatest tropes in this discourse precisely the separation between ‘art and life’, or between the concerns of ‘after-life and life’?

The myth of the saint, which has an extensive history from the Roman Christian era to well past the middle-ages, is re-elaborated in our present age as the myth of the artist, that precociously illuminated, infinitely sensitive, candid introvert, divorced from ordinary people by virtue of the very talents that elevate him / her above the world. This character is at the heart of such works as James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man or Thomas Mann’s Tonio Kroger. Baudelaire sums up the character in the famous ending to his poem The Albatross:

But there is another dualistic opposition in our culture that places science at one end and a specific discipline at the other. This is the slightly vaguer opposition of science and art. We find it encapsulated in the more general dichotomy that is manifest in our education system, that of the sciences versus the humanities. A student is normally expected to orient him/herself in the direction of one of these two, with a number of congruent modules in either of the fields. Furthermore the figure of a great artist, along with that of a great scientist, is presented to us from early childhood as pretty much the purest and noblest aspiration available in this world (not necessarily to the point that we are encouraged to become one, but at the least we are taught to admire them). More importantly, they are the only two models which subsist in a dichotomous relation. No similar bridges are raised between, say, the aspirational figure of a great athlete and that of a great businessman, or that of a great statesman and a great engineer (though these are themselves celebrated). The artist and the scientist seem intuitively related, as though linked by a thread which simultaneously aligns and opposes them to each other.

This commonality between art and religion as cultural ‘others’ to science also points to a commonality in their perceived social role. As disciplines, it is obvious that art and religion are two very different things. However, our culture has developed a way of talking about them – a unified set of clichés, myths and rhetorical figures – which are at heart identical for both. What exactly is the nature of this similarity, why does it persist, and what should be done about it?

Let us begin by exploring the first question. What are the common traits between artistic and religious discourse? What is the (linguistic) emblem that describes both of them? Or, more simply, what are we talking about, traditionally, when we say either ‘art’ or ‘religion’?

To begin with, we are talking about something that is specially recognized for its preciousness; the word we use for religion tends to be ‘holy’, whereas the word we normally use for art is ‘priceless’ (both terms have a similar function – they ban any discursive element with commercial connotations). Economic considerations do not come into it and are in fact considered vile. The real man or woman who follows or engages with this discipline is always expected to think nothing of money, but rather to be wholly dedicated to the object of his / her endeavour. This is understandable, because his / her discipline is not amenable to mathematical models and has no quantifiable dimensions; rather, it defines our society’s ethical standards and helps us find the best way to live our lives, either by teaching or simply by suggesting; it explores and sometimes explains the best path(s) towards happiness, on the strict condition that we be true to ourselves (when our ‘selves’ do not correspond or agree with the work of art or with the dominant religion, this leads to conflict and paradox – as usually explored in minority discourse). As such, it is culture’s primary source of opposition to inducted values such as consumerism or materialism, acting as a stalwart against greed and superficiality. It (supposedly) trains our sensitivity and kindness as well.

Naturally this object that we are talking about is transcendental. Perhaps more significantly, it is an end in itself. Though it benefits society as a whole in a number of ways (Dawkins has contended this bit with respect to religion), it can also be done for its own sake, and indeed is primarily approached for this reason. As a self-sufficient ‘end’, and thinking on a grander scale now, it justifies the whole of humanity. It redeems it, both individually, acting on its people one by one, and also historically. A civilisation may legitimise its course and passage over the face of the earth if it leaves us with a heritage of great art or if it greatly contributes to the spreading of the Word, which is the same thing. It can also attain the same recognition if it greatly advances science – but that’s the other end of the spectrum.

Since in both the cases of art and religion we are talking about what is essentially a discipline, it only rewards in degrees commensurate to the efforts that are put in. It is of little use if it is treated casually, or if it is only thought of in passing, once every now and then. People who handle it this way are regarded with paternal benevolence by those who take it seriously instead (but with frequent encouragements to ‘practice it’ more often, be it by coming to the prayer sessions or by reading the poems of Coleridge / Milton / Neruda…). A serious commitment to this discipline demands long hours of study, a deep acquaintance with the history and culture of your specific ‘school’, and a great deal of introspection. The implicit reward of all this is a certain happiness, of course, but also a special type of wisdom. This may loosely be referred to as ‘enlightenment’, according to its manner (and maybe suddenness) of acquisition. Emphatically, depending on the subject, we may even talk of salvation.

The general conception is this – that though the reward of the discipline is available to everyone, for it is not precluded by class, sex or race, in practice only a handful of people actually attain it. The hierarchy of success, here, is aristocratic: it is defined by a special gift known as ‘talent’ in art and as ‘piety’ in religion (the importance of piety has greatly declined since the times of the legendary saints, but so has proactive religious discourse in general – more on this later). Societies go to great lengths to celebrate individuals with this special gift, and very many of our legends are woven specifically around these people (the only discourse which compares to the spiritual one for mythopoeic power, in fact, is that of war). Therefore in this discipline we find prophets and martyrs, people who see ahead of their time and reveal to us the real nature of things, sending out messages which are then misunderstood or fearfully rejected, or people who die for their commitment to their private cause, thereby becoming instant icons, worshipped past all others, even to the point of eclipsing the real value of their work. After all, they demonstrate the transcendental value of the discipline that they upheld; for is it not worth dying for? Is it not larger than life? And is not one of the greatest tropes in this discourse precisely the separation between ‘art and life’, or between the concerns of ‘after-life and life’?

The myth of the saint, which has an extensive history from the Roman Christian era to well past the middle-ages, is re-elaborated in our present age as the myth of the artist, that precociously illuminated, infinitely sensitive, candid introvert, divorced from ordinary people by virtue of the very talents that elevate him / her above the world. This character is at the heart of such works as James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man or Thomas Mann’s Tonio Kroger. Baudelaire sums up the character in the famous ending to his poem The Albatross:

The Poet is his kinsman in the clouds

Who scoffs at archers, loves a stormy day;

But on the ground, among the hooting crowds,

He cannot walk, his wings are in the way.

A step below the ‘chosen ones’, the saints and great artists, the discipline then includes a whole set of subordinates whose role is to mediate and explain: religion has priests, and art has academics and / or critics. This without mentioning the legions of novices, in schools both improvised and recognised.

Keep reading in Part Two…

Keep reading in Part Two…

Sunday Review: The Lucky Star of Hidden Things by Afric McGlinchey

posted by the Judge

Not sure if Santa’s going to be reading this one, with all the stuff’s he’s got to go through, but here’s our Sunday review: Ian Chung takes a nice long look at Afric McGlinchey’s The Lucky Star of Hidden Things.

Take a nice long look at his review, via the above link.

Have a fantastic New Year’s, and end it the way you began the day. (That would be: lying down. If you began it by doing something else, then by all means do something else).

Not sure if Santa’s going to be reading this one, with all the stuff’s he’s got to go through, but here’s our Sunday review: Ian Chung takes a nice long look at Afric McGlinchey’s The Lucky Star of Hidden Things.

Take a nice long look at his review, via the above link.

Have a fantastic New Year’s, and end it the way you began the day. (That would be: lying down. If you began it by doing something else, then by all means do something else).

The Next Big Thing

I’ve been tagged by the very talented Melissa Lee-Houghton to give this interview for an expanding blog project called The Next Big Thing. You can read her interview here.

The idea is I post mine and tag other writers to do the same on 2 January 2013.

Where did the idea come from for the book?

The title for Never Never Never Come Back came from the Al Stewart song ‘Night Train to Munich’, which adopts the voice of a senior agent instructing their colleague on an operation from which they may not return. I wanted my first collection to have the combination of paranoia and loneliness that plague the classic spy figure; distrusting everyone, under pressure to deliver something valuable without knowing why.

What genre does your book fall under?

Poetry

What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition?

Many of them are actually based on films and programmes anyway – ‘Supper’ focuses on a scene from Soylent Green, ‘Yokohama Shopping’ on the anime series of the same name and ‘Schoolgirl Shootout’ on the tragic lighthouse blitz in Japanese thriller Battle Royale. Maybe Tilda Swinton for the metal ex-assassin in ‘Roy’. I’d quite like to see Rutger Hauer play Armin Meiwes. Cillian Murphy would take on the more lovelorn, gawky characters, while the main role in ‘On coming out to your parents dressed as Dracula’ could only go to Sam Rockwell. I love that man.

What is the one sentence synopsis of your book?

Wheeling a broken bike through an embarrassing dream in which nobody else is naked, nobody else has forgotten their gift and everyone else knows the words to the song

How long did it take you to write the first draft of the manuscript?

Very hard to tell, though I think only one of the poems (‘Splitting the ego with Mary’) was more than two years old when we put NNNCB together. Most of the poems came from NaPoWriMo 2011 and 2012, which tends to dust under the corners of the brain where the weird stuff lies. The putting together and sifting of the poems took about six months with editor Roddy Lumsden.

Who or what inspired you to write this book?

Everybody is under pressure to fulfill multiple roles at once, relating to this idea of a person they’re advised to become. I wanted to probe the idea of breaking down under this brick-filled rucksack, of the ludicrous rules that can quietly destroy people. Poetry, with its restrictions, concentration of language, repetitions and cycles, seemed like the best form in which to explore this.

What else about your book might pique the reader’s interest?

A good helping of robots and at least one German cannibal.

Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency?

Neither. Never Never Never Come Back was published by Salt Publishing in 2012. No agencies were harmed in the making of this book.

***

My writers to tag are:

1. Hong Kong-born poet, author of Summer Cicadas and Chinese translator Jennifer Wong

2. Leicester native, author of hydrodaktulopsychicharmonica and birdman Matt Merritt

3. Reportage poet, ukelele demon and Blake afficionado Jude Cowan Montague

4. International poetry evangelist, collaborative tinkerer and all-round alchemist SJ Fowler

Make sure you check them out on 2 January 2013!

The idea is I post mine and tag other writers to do the same on 2 January 2013.

Where did the idea come from for the book?

The title for Never Never Never Come Back came from the Al Stewart song ‘Night Train to Munich’, which adopts the voice of a senior agent instructing their colleague on an operation from which they may not return. I wanted my first collection to have the combination of paranoia and loneliness that plague the classic spy figure; distrusting everyone, under pressure to deliver something valuable without knowing why.

What genre does your book fall under?

Poetry

What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition?

Many of them are actually based on films and programmes anyway – ‘Supper’ focuses on a scene from Soylent Green, ‘Yokohama Shopping’ on the anime series of the same name and ‘Schoolgirl Shootout’ on the tragic lighthouse blitz in Japanese thriller Battle Royale. Maybe Tilda Swinton for the metal ex-assassin in ‘Roy’. I’d quite like to see Rutger Hauer play Armin Meiwes. Cillian Murphy would take on the more lovelorn, gawky characters, while the main role in ‘On coming out to your parents dressed as Dracula’ could only go to Sam Rockwell. I love that man.

What is the one sentence synopsis of your book?

Wheeling a broken bike through an embarrassing dream in which nobody else is naked, nobody else has forgotten their gift and everyone else knows the words to the song

How long did it take you to write the first draft of the manuscript?

Very hard to tell, though I think only one of the poems (‘Splitting the ego with Mary’) was more than two years old when we put NNNCB together. Most of the poems came from NaPoWriMo 2011 and 2012, which tends to dust under the corners of the brain where the weird stuff lies. The putting together and sifting of the poems took about six months with editor Roddy Lumsden.

Who or what inspired you to write this book?

Everybody is under pressure to fulfill multiple roles at once, relating to this idea of a person they’re advised to become. I wanted to probe the idea of breaking down under this brick-filled rucksack, of the ludicrous rules that can quietly destroy people. Poetry, with its restrictions, concentration of language, repetitions and cycles, seemed like the best form in which to explore this.

What else about your book might pique the reader’s interest?

A good helping of robots and at least one German cannibal.

Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency?

Neither. Never Never Never Come Back was published by Salt Publishing in 2012. No agencies were harmed in the making of this book.

***

My writers to tag are:

1. Hong Kong-born poet, author of Summer Cicadas and Chinese translator Jennifer Wong

2. Leicester native, author of hydrodaktulopsychicharmonica and birdman Matt Merritt

3. Reportage poet, ukelele demon and Blake afficionado Jude Cowan Montague

4. International poetry evangelist, collaborative tinkerer and all-round alchemist SJ Fowler

Make sure you check them out on 2 January 2013!

I’m Walking Backwards (but looking forwards) for Christmas

Just a quick post to say thank you to everyone for a great year. Sidekick Books has had a tiring but good 2012, putting out the second part of our four-volume tribute to Britain’s birds, Birdbook II: Freshwater Habitats, and the long-awaited print version of Simon Barraclough’s Hitchcock tribute Psycho Poetica.

Whether you’ve written for us, illustrated for us, bought books, come to readings, evangelised about our strange schemes online or simply investigated the dark world of Dr Fulminare in passing, we appreciate it and will continue to provide characteristically Sidekick weirdness in 2013.

K x

Whether you’ve written for us, illustrated for us, bought books, come to readings, evangelised about our strange schemes online or simply investigated the dark world of Dr Fulminare in passing, we appreciate it and will continue to provide characteristically Sidekick weirdness in 2013.

K x

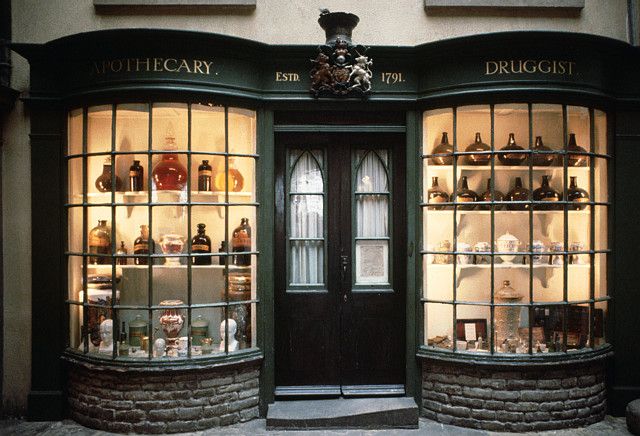

Sunday Review: The Apothecary’s Heir, by Julianne Buchsbaum

posted by the Judge

The last Sunday before Christmas. A silent night, a holy night… no-one mentioned it was supposed to be such a COLD night.

To warm your spirits, here’s some Baileys… nah, I kid, I kid. What I can give you instead is our Sunday review, which deals with Julianne Buchsbaum‘s The Apothecary’s Heir. It’s a pretty big deal, as it’s been chosen yonder in the US of A for the National Poetry Series. Rowyda Amin, our specialist beyond the Atlantic, tells us all about it in the article.

What the heck, it’s impossible not to close with these words. Merry Christmas everyone, and have a glorious 2013!!