This is what you call a passable introduction to the concept of history in the modern and postmodern age. Or at least that’s what I called it, elsewhere.If you’re reading this, my guess is that you must have clicked on the link

in my video review of Other Countries, the poetry anthology edited by Claire Trévien and Gareth Prior. I should start by saying this little article isn’t required reading for the review – it’s more like some side-stuff that I felt I had to specify (mainly to show that yeah, I’ve done my homework, I didn’t just caper into the review like a blindfolded kid swinging for a piñata).

In fact, this was meant to be the introduction to the review before I realised it was going to be longer than the goddamn review itself. But let’s start the way a proper essay is supposed to start – not with my proverbial verbigeration, rather with a short paragraph that is related to the topic and has some semblance of intelligence.

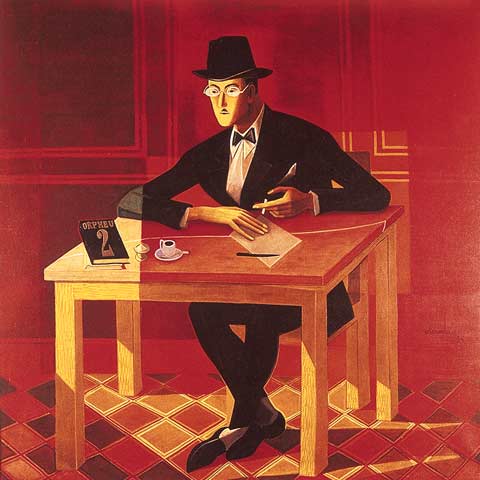

*ahem*James Joyce’s

Ulysses [what better book for that ‘semblance of intelligence’] must have, I don’t know, something in excess of 10,000 sentences. If I told you to quote a line from that book at random, and unless you’ve got a PhD on the guy and can recite

Penelope backwards, chances are you’ll drop this little cultural bomb:

History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.

This is one of the most famous and widely-quoted lines from that particular novel. Now the fact that this particular shibboleth topped the other 9999 or however many there are in that grotesquely long book is indicative (I think) of how Modernism adopted the problem of history as one of its central literary and philosophical concerns. Or should I say, not ‘the problem of history’ but rather the Problem of History, because approaching history as a problem(atic) is kind of a shtick for the Modernists and their particular articulation of this Problem deserves something like a circled R or a TM logo next to it. But we’ll get back to that.

So for starters, and as long as we’re looking not at history but at the way we understand history, let’s break down the Joyce sentence.

a.) History is a nightmare

b.) from which I am trying to awake.

These two parts of the sentence are saying different things. The first part gives history a negative connotation – the topic means bad shit, because it’s more like a nightmare than a dream. The second part implies that history is deterministic, and it characterises the Problem of History TM as attempting to wake up – the trying bit is the really important verb there, not the waking up, because it brings focus on the tension between failure and success in volition, a.k.a. the struggle between determinism and free will. The problem of history is therefore how to abandon determinism and gain awareness and control of one’s own actions (where this implies, in that particular sentence, leaving history itself).

Given the status later invested on

Ulysses, I think this next statement has some grounds: at some stage among the finer European minds it became commonplace to view history as something both negative and deterministic (perhaps, but not necessarily, negative because deterministic).

This is not to say that this was the only way of thinking about the subject – see the rise of fascism,

which coincides with the year of the publication of Ulysses, as one example of a powerfully different understanding of history and its forces that coexisted (not exactly amicably) with The Problem TM.

But the Joycean approach is the one that became most pervasively linked with the humanities, pointedly with literature – which is why I think of it as a good starting point to discuss

Other Countries and its particular approach to history. (For that matter, it’s also adequate to discuss much other contemporary poetry – including

one that I reviewed some time ago and which still formulates The Problem TM).

But if I am right and

Other Countries traces its own intellectual history to the Modernists (as championed by Joyce), then it’s worth investigating that point of view more in depth. The way this is done is, of course, to consider the history of that phrase on history (which itself represents the history of Trévien and Prior’s anthology on history… it gets convoluted). So, let’s.

SO, as concisely as possible – you can trace the notions that history is negative + deterministic to a few general cultural currents.

The notion of history as deterministic has a counterpoint – and in this sense is perhaps reactive – because our oldest (recorded) way of understanding history is based on the opposite idea: that individuals, in particular Great Individuals, are the ones who shape history. For convenience we can call this the Classical school of history and its roots start (at least) with Homer’s epics, at a time when the notions of history, myth and poetry were not quite as distinct as they are today. Read the story, and see what I mean – the events of the

Iliad, which was meant at least in part as an historical recollection, are generally decided by the kings and the heroes (albeit guided by the gods), not by the movement of troops and seldom if ever by accident. The fact that other Classical historians, from Herodotus to Cassius Dio, took a more rigorous approach to the question of veracity and often discussed cultures and people as a whole is not enough to suggest that they diverged from or even questioned the central Classical tenet: History is shaped by Great Men (and, less readily allowed for, Great Women).

In fact, the person often considered the world’s first female historian, Anna Comnena, was largely a biographer (of her father Alexius I). The point being that history and the life of (great) individuals were geminate concepts, and they stayed that way for thousands of years (especially when the epics came in to contaminate the subject… it’s kind of striking how closely to each other

Os Lusíadas and

Jerusalem Delivered were written, and how closely both of them stick to the Classical model established by Homer).

Now the (relative) decay of this Classical paradigm – starting, one may hazard, somewhere in the late 18th Century, though no doubt the roots go further back – goes hand in hand with the rise of a number of intellectual schools that viewed Great Individuals as increasingly less important, Marxism being the most famous. (I say relative decay because Classical history still had its champions – John Stuart Mill, for one – but my impression is that by that stage the topic was kind of dead, and had no innovation, against the rapidly and continuously changing sciences of the history of collectivities, from Rousseau to Marx and Durkheim).

One (kind of inflammatory) way of responding to the Modernist take on history is to say that this is simply the humanities playing catch up to schools of thought that preceded it – remember that Marxism did not restrict itself (like it does nowadays) to the humanities, and that

LaPlace’s Demon dates back to 1814. But of course that’s not true, because this cultural transition was part of a very gradual process that affected all areas of human understanding simultaneously, including literature and the arts. What I mean is that, as far as the humanities were concerned, there was a heightened sense that individuals were the product of circumstance in much the same way that astronomical events were seen as the product of physical forces (LaPlace) and historical events as the product of social forces. ‘The child is the father to the man’ etc. but you find this notion most pointedly in proto-modern novels: Stendhal, Balzac, Verga, Flaubert, Mrs Gaskell, Zola, Turgenev, or George Eliot. In fact, you could argue that the rise of the novel’s omniscient narrator – from the ashes of the epistolary novel – was in itself symptomatic of a cultural application of the assumption behind LaPlace’s Demon… that knowing and explaining everything is, at least conceptually, a possibility.

I should probably quote Leo Tolstoy’s

War and Peace here

because it makes me look so clever because it’s so relevant. I don’t know if you’ve read that thing – it stands to a literature degree kind of like

Cat Mario stands to this guy’s job – but that thing is a monument to determinism. It spends 1300+ pages telling you essentially that history goes its own way and that no man or woman can do anything to steer that. If you want quotes, I’ll give you the One To Rule Them All & In The Shadows Bind Them:

Kings are the slaves of history. – Tolstoy,

War and Peace.

(Now – and to be clear – I don’t want to make a totalising argument here. I understand that these matters depend greatly on perspective, as you could argue – for example – that Homer’s use of the gods in the

Iliad is metaphorical to say the same things that Tolstoy is saying, much earlier. Bear in mind that I’m just identifying general trends, not putting them on an altar at the exclusion of all others).

As for the notion that history is ‘negative’, this type of historical pessimism is grounded – in my opinion – in the same type of currents that later provided the groundwork for existentialism. This too includes Marxism, mainly for its open atheism, which – interestingly – it shared with some of its most outspoken antagonists too (Nietzsche). In this case tracing back a tradition is much more difficult because ‘pessimism’ is a much vaguer concept than ‘determinism’, and you can find it on whichever side of the fence you wish to construe it, e.g., you could make an argument that the rise of certain atheistic currents nourished the historical pessimism of

Ulysses, because the possibility of transcendental salvation and redemption were being denied; hence the spiritual crisis that later led to existentialism. But it would be only too easy to point to Jansenism or Gnosticism as examples of religious pessimism that are every bit as bleak as anything written by Leopardi, Baudelaire, or Schopenhauer.

OY FRIGGIN’ VEY!!!! So what’s my point? Well, aside from the fact that I’m doing exactly what people always do when they deal with history – getting entangled in the enormity of the things I’m trying to disentangle – I guess I’m just trying to sketch something like a backdrop to contemporary discussions of history in the humanities, particularly in literature.

I mention this specifically with regards to

Other Countries (this was in fact meant to be my introduction, but it seems like I pulled a George RR Martin and quadrupled my own word-limit), because I feel its decision to discuss history through minority discourse – without acknowledging the limits of this decision, i.e. as though it were possible to treat the whole topic through those comparatively small lens – re-echoes The Problem TM. In particular it seems to buy into the notion that there’s a ‘dominant’ (and noxious, ergo pessimism) historical narrative that minority discourse can and should subvert. This has a trace of Marxism because it shares that ideological view of history as being organised according to a linear hierarchy (classes at the top & at the bottom – then, by extension, some narratives at the top & others at the bottom).

I’d argue that this is one of Marxism’s most obsolete positions – complexity science, which is increasingly being adopted to describe economics (and therefore is inextricably linked to history as a whole) shows that the most dynamic systems are those in which behaviour emerges spontaneously out of the interaction of a variety of forces, none of which need be dominant. Hierarchism is another form of the Classical tenet, except that instead of Great Individuals you postulate Great Classes, and you focus only on those at the expense of all else. Complexity theory seems much more intuitively linked to the behaviour of such undeniably complex systems as society, culture and history, and – crucially – it seems to include an inherent understanding of its own limits. But now I really am rambling (and colouring this introduction with my own biases and preferences). This was meant to be an introduction – probably more useful to exorcise the bits that couldn’t get into the review than as something that anybody is going to read (yes,

I’m making this a habit) – and it has more than exhausted its function.

Vir sapit qui pauca loquitur, let’s close it on that.