Let’s talk war poetry. Not Wilfred Owen, not Giuseppe Ungaretti, not any of the poets who wrote of that old war (it is a hundred years ago now, so I guess it counts as old). Let’s talk of war poetry today, and how it differs and resembles the efforts that defined the category, set a standard, and laid out the rules.

Among the various books that I’ve been (very kindly) sent to review, I count two that belong to the genre. One is

Letter Composed During a Lull in the Fighting by Kevin Powers, which David Clarke

reviewed not too favourably last week. The other is

War Reporter by Dan O’Brien, which I didn’t send out to my critics because I wanted to review in person. I’ll have to base my article on these two sources because, I liberally admit, I don’t know any other contemporary war poetry – if you have suggestions, my e-mail’s

at the end of this page.

I’m less than halfway through reading O’Brien’s book and my inclination to review it is already dwindling. It’s not that the verse isn’t good. Not at all: O’Brien has a real talent for imagery and his poems are subtle and rich, evoking the poet’s own life as well as his strange relationship with war photographer Paul Watson. Perhaps it’s just the fact that I was looking for something else. I was looking for war poetry, and neither of the two books delivered (yes, I read Powers as well before sending it to David, though not with the same levels of concentration I’d dedicate to something I’m reviewing).

Hold on a second – how are these books not war poetry? Isn’t Powers a genuine veteran of the war in Iraq, speaking / writing from lived experience? Aren’t O’Brien’s poems stark and real and full of the unchanging horror of war? Take these lines by the latter poet:

On a bed we discover the body

of a child at the bottom of a pile

of dead children. Quartered like chickens. Outside

another’s buried alive. The hand is

like a tuber. At the refugee camp

a girl stumbles barefoot into a ditch

of corpses. Some wrapped in reed mats. Looking

for help, crying. But nobody’s coming.

I say to myself, This will make a great

picture. This is a beautiful picture

somehow. Raising my camera to my face

I step on a dead old woman’s arm: it

snaps like a stick. In Nyarubuye

we open a gate on a courtyard

of Hell. Tangles of limbs junked. They’d come to

this church hoping God would protect them but

it only made things that much easier

to be hacked to pieces. […]

(‘The War Reporter Paul Watson on Suicide’).

Isn’t this just the gruesome reality of war? Aren’t these the words of someone who jumped down the black shaft of war and came back to tell us what it’s really like? Isn’t this enough? What more do you want? How horrifying does it have to get before you recognise it as genuine war poetry?

|

| No more words. |

It’s probably a good idea at this point to state my respect for Powers, O’Brien, the photographer Paul Watson and anyone else who lived through this unspeakable inferno. As David noted in his review, there is only silence that makes for an appropriate response to this suffering. I don’t know what they know, and in this particular case I am grateful for not knowing.

That being said, there is a problem here and our inability – our unentitlement – to respond to this kind of imagery is part of it. Contemporary war poetry is not unlike World War I poetry in its occasional tendency to make a catalogue of horrors. But one of the crucial differences between the two canons is context. WWI poetry was written at a time when war was highly romanticised and patriotism was seen as a basic moral standard. Indeed, war poetry of the times includes the writings of young romantics like Rupert Brooke who extol the beauty and the nobility of war (before they saw it, anyway).

The merit of the war poets was that of reinventing the imaginary of war (or, should I say, erasing the ‘imaginary’ bit). It said that war was hell at a time when people were saying that war was god. Reproducing the crude horror of war was part of that task of reconfiguration.

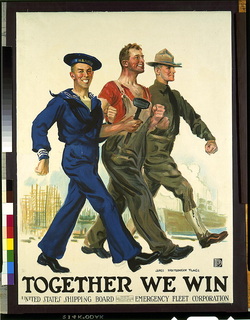

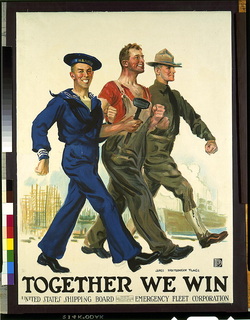

|

| Off to war with a smile. Yeah, it doesn’t fool anyone any longer, does it? |

Contemporary war poetry appears at a time when society speaks in a very different voice: the lines on limbs flying and children torn to pieces are horrifying, yes, but also kind of a given. They feed the reader of war poetry what s/he wants to read from war poetry, which is what s/he thinks people don’t want to read. Not only are they customary, they also risk falling somewhat short of their peers in other media: no matter how good your language is, it’s a damn challenge to reproduce the visceral impact of seeing the effects of steel and fire on flesh as we get them in every war movie since Saving Private Ryan (so much so that it’s hard to even shock us anymore – carnage may leave us dumb, but sometimes it leaves us dumb with boredom, because we’ve seen so much of the ‘mutilated arm’ and the ‘hand holding his own guts’ and the ‘neck torn open so I only have a line of breath to say write to my family dear brother’ and so on).

If war poetry from one hundred years ago was radical, contemporary war poetry is conformist. Certainly, it has more levels of reading (O’Brien is especially subtle, but from what I’ve read so far his subtlety doesn’t invalidate any of my criticisms), and it is more delicate in its approach than Spielberg’s bombast, but it’s still treading much of the same ground, where you know that nobody hid any mines.

You may ask, what more can be said of war? What more should be said of horror but to say that this is the horror? Again, I must qualify my arguments by saying that this is not about the experience of the war poets in and of itself. I’m not discounting that – how could I? The problem in this case is not the poet, it’s the reader.

War poetry changes because war changes. The classical war poets were responding to a new form of war – a mechanical type of warfare that brutalised the mind to the point that even a body all in one piece could be made useless, that blasted the land and made the skies permanently grey, that corroded your insides with chlorine gas. It was a new type of war – of course it called for a new type of poetry.

War, in the last hundred years, has changed again. It has changed more radically than poetry has. Notin the way that people die – that’s the crucial thing. It’s not that Powers’ statement, that ‘war is just us / making little pieces of metal / pass through each other’ is substantially dated. It was as true a hundred years ago as it is true today. It may well be true a hundred years from now, if nobody’s taken war seriously enough that (you know the rest, & God forbid).

But here’s the thing: it’s not the experience of soldiers that has changed, it’s the way that society metabolises that experience that is different. Calls to patriotic fervour no longer take the shape of softness – they seduce with hardness, with violence, with the same language that supposedly should deter you from war – the same language, of course, invented by the classical war poets. Old war propaganda was a lap-dance: it seduced by suggestion. Contemporary war propaganda fucks you hard and tells you that you like it. It tells you that you know you like it. It doesn’t sugar-coat its product: it makes it as hard to swallow as possible and then challenges you to down it. It borrows the manly contest from bars, where it really works because everyone loves it.

From this point of view contemporary war poetry is just another form of war propaganda. You’re not going to convince young people not to go to war by describing piles of dead bodies because that’s exactly what young people are setting out to see. The spectacle of war has replaced war: it is the idea of going to hell and back, of being able to say ‘I’ve been to hell and back’, that defines the beauty of war (and yes, it’s beauty – for in the words of Alessandro Baricco, ‘no pacifism today should forget or deny that beauty or pretend that it never existed; only when we will be capable of a different beauty shall we be able to dispose of the beauty of war’.)

The reality of contemporary warfare may still involve blood on the bricks, but the experience of war that really matters, the experience that sells and motivates us and keeps us interested, the experience that lets war happen, belongs to those who live at home. In the West, where we write and read our poetry, war no longer invades our land. It no longer burns down our cities or rapes our women. When the ‘enemy’ does make an appearance in our cities we call it terrorism, which is something else. War today happens far away and to a restricted number of people. It happens on a TV screen, which is kind of like saying that it doesn’t happen. In the sense of human loss one may be justified in saying that war is a business of negligible import to the Western countries: compare the 5000 American soldiers that died in Iraq since 2003, with the 383,000 that died in car accidents in that same country starting from the same year. One almost wonders whether the war really worth fighting is not in our roads, rather than in the desert. And let’s not get started on workplace deaths. Let’s not get started on drugs.

These numbers do not include the real victims of war, that is to say, the people who did not do the invading – the civilians, who die by the hundreds of thousands. I’m not forgetting about them, at least no more than the war poets themselves are – both Powers and O’Brien seem more interested in their own experiences and what war says to them or their friends like Watson. The victims only matter to the extent that they inform the experience of the poets: like war itself, they’re just images.

But the material reality of these civilians is another expression of how war has changed. It used to be a conflict between two sides subject to equal conditions, it is now a conflict with no mutuality in which only one part does the invading, the killing, the filming, the TV reporting, and – on the long run – the war poetry.

In my opinion, which is as humble as it can be without being tacitly conformist for that, the mistake of contemporary war poetry is that of being about war. If it is true that

the Gulf War did not take place, then it is reasonable to assume that all the other wars since then have not happened either: that they took place in the media, and not in the battlefield; that they exist not for the lands that they invade but for the share of audience that they annex; that the role of the modern war is not to conquer: it’s to

convince.

If that’s true, then what should war poetry do? I don’t know, of course, but one possible answer is: the opposite. Like in the old days: say the opposite of what is being said by everyone else. Don’t convince me that war is terrible, cause everyone is already doing that: convince me not to be convinced. Show me that war is there because of me, thanks to me, not me the soldier, but the one who stands on the side-lines looking at the soldier as though he were an athlete, or an actor. Show me that the story of war is best sold when it is most authentic and it is most authentic when it is most brutal and it is most brutal when it is most distant. Show me the war that takes place not worlds away but in my taxes and in my passport and in my internet. Show me not the experience of battle but this new and very silent type of war that makes do with experience and replaces it with media reports. Show me that the horror is not what is shown through their videos, it’s what is created by them. Show me war in the 21st Century. And I’ll believe you.