The second part of our article wishes to discuss the practical aspects of engaging with international poetry. It is dedicated to those who entertain an aspiration to do so. Readers uninterested in putting in the (considerable) work required to branch out of their own poetic culture are welcome to discard it, and should be aware that this article does not wish to pressure anyone into such a study. There is no moral or cultural obligation to read poetry from other countries, any more than there is to read poetry itself. It is not mandatory towards becoming a good poet or a good critic, even though it is indispensable if one wishes to take part in the European discourse that is coming to permeate the rest of the continent (and which is leaving England behind). For the rest, the benefits of approaching international poetry are your own to discover as well as to dismiss, and they can only be termed benefits as long as they are understood as a choice, and not a requirement.

We mentioned the ‘considerable work’ that is necessary to approach international poetry. This is almost entirely related to the process of learning the foreign language of your choice. The challenge involved in finding and researching the poetry is negligible; when approaching a new poetic culture, you will invariably find that selections of local verse have already been made for you, and good material is never too hard to put your hands on, provided that you can access the foreign country you are studying (yes, you do have to go there in person – most of the contemporary material has yet to be translated, and much of it never will be).

Learning the foreign language, however, is the sine qua non of all international poetry. Bilingualism is required even when reading translations into your mother tongue – you must have an understanding of how another language allows for forms of expression that are not possible in English. Lacking this fundamental prerequisite, even finding books in translation does not help, and will never take you past a certain superficial stage.

Thus, engaging with ‘international poetry’ should really be understood as engaging with only one foreign culture. You may expand that number to two or three, but in prospect, as you can only really learn one language at a time. Any use of the expression ‘international poetry’ that is not grounded in this dualistic exchange, and that wishes instead to discuss a global (or otherwise polycultural) scene as a whole, is a fiction by default. Distant poetic cultures do not interact with each other except after centuries, and sometimes not even then (the most potent proof being that literary titans such as Camoens, Mickiewicz or Tasso may remain not only unread but frequently even unknown – not by the common folk, but by the poetry pundits themselves!). And there is no such thing as a global poetry expert – to gain a working knowledge of what is going on even in one continent is a colossal task, one made all the more endless by the fact that smaller countries do not necessarily have correspondingly modest poetic outputs at all (Nicaragua, for example, has a tremendously vital scene which rivals that of other, larger Hispanic countries).

The only reasonable way to approach international poetry, then, is to choose one foreign culture (and language) of special interest and stick with it. This does not mean that you will forever be limited to your initial choice, but it is the only way to start.

Since you can only begin with one language / culture, your choice has to be carefully meditated. Countries very far away will be very difficult but also exotic and fresh, and to people around you, you will become an authority almost by default. Closer cultures and languages will be easier, and you will have many peers: this means greater competition if you wish to use your multilingual skills in criticism or publication, but also greater opportunities for sharing and communicating. Some of them open up new doors. Fluency in Spanish gives access to the entire South American continent bar Brazil, Russian is a popular second language in many Eastern European nations, and French is spoken in Canada, Africa and parts of South East Asia.

Learning a foreign language is a strange prospect. When polyglots are faced with the need of learning a new tongue, they generally approach it with excitement, and their initial progress can be very fast. People who only speak one language, by contrast, often find the whole idea dispiriting, and are slow to get into it. In reality, it is just as hard (or as easy) for both groups. People who already speak multiple languages are only more familiar with the process of learning, and they know that obstacles which initially appear insurmountable (and illusions about one’s own inability or lack of talent) require no more than a little time to be dealt with.

Learning a foreign language does not require exceptional intelligence, and it should be an option available to anyone smart enough to read this article. It does, however, demand strong commitment and patience. Like learning to play a musical instrument, it is a task that takes several years, and in which perfection can never be attained. It is almost impossible to learn only with books, so be prepared to take periodical trips to your country of choice. This is where the European Union becomes helpful. A return flight to a European capital will cost you less than one hundred pounds, with no need for visas; such a trip can be taken several times a year, over weekends if necessary. Flying to Asian, African or American countries will be priced from five-hundred to more than a thousand pounds, and the bureaucracy can be demanding and limiting. Along with the difficulties inherent in exotic languages, one understands why there are so few people who can speak Lingala or Bali.

Tackling foreign poetry means tackling the entire culture that produces it. You are unlikely to understand a poem that references a Bollicao if you don’t know what that is. This is why personal trips to the chosen country are so important, and this is also where learning a foreign language will truly reward you. Of course being able to read Dante and Baudelaire in the original is very nice, but the most surprising material is normally that which does not get translated. Finding out that a country has an entire comics culture that you knew nothing about, or a colourful underground rap scene, or a completely different approach to sports journalism – that’s when the language discloses itself to you, and really shows its benefits. Hopefully, poetry will help you on this path. You may learn a language in order to read poetry, but past a certain level the relation becomes reciprocal, and poetry in turn starts teaching you the language, adding new words to your vocabulary, new turns of phrase to your repertoire, and a new musicality to your cultural ear.

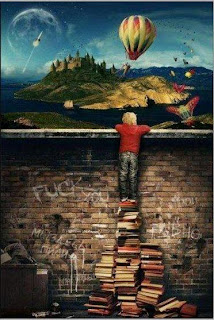

Engagement with international poetry, like engagement with poetry itself, is necessarily proactive. You must go to it, it won’t come to you. This is one of the reasons why lamenting the absence of more translations into English misses the point – no matter how many translations there are, you won’t really get much out of foreign poetry if your viewpoint remains anglocentric; if it remains rooted in the idea that things must go towards English, and not you past that bridge. Changing this perspective may be one of the most difficult things to do, especially for poets born in a culture that neither demands nor encourages learning a foreign language. But it can reward you by opening many doors you did not even know were there, and by giving access – better, perhaps, than anything else – to the particular and fascinating European multi-cultural discourse that defines this continent’s historical moment. Make your own decision as to whether that’s worth the price of admission.