International poetry is a difficult topic. It is the specialised branch of a specialised branch: since there are few people reading poetry, it follows logically that only a very select few will read poetry from multiple countries as well. Linguistic barriers are among the most challenging to surmount, and the fact that England has one of the least polyglot cultures in Europe does not exactly help. The first part of this article wishes to discuss some of the characteristics of the current international (and especially European) poetry scene when seen from the English perspective. It is not intended to be an exhaustive or final article on the topic, only an introduction to some of the issues and problems that surround it. The second part will discuss the question of how to approach international poetry in practice.

The political reality of our continent, to the extent that both alliances and rivalries are now mediated by a common regulating body, has in the last half-century increasingly come to be defined by the European Union. Linguistically, we have therefore seen the rise of English as the union’s official language – and this is a matter of great consequence for scholars of poetry. Previous centuries saw intellectuals learning a foreign tongue primarily (though of course not exclusively) for two reasons: so as to be educated in the language of the dominant power, or else for an historical purpose. The former case is well exemplified by the French language, which was learnt and employed between the 18th and 19th Centuries by the English Romantics, by the great Russian novelists and by an assortment of literary figures (Giacomo Casanova, for example) on account of the political and cultural influence held by France. As for the second purpose that we mentioned, it refers to the popularity held by Latin and Greek in the continent’s educational curricula (at certain points, Italian joined that group as well, as the language that gave access to the great medieval authors).

Both these registers have fallen away. The language of the dominant power is now American English, and the popularity of dead languages – even among the educated – has been largely replaced by an unprecedented interest in the living languages of our neighbours. Our relationship with international poetry is now defined – even if unwittingly, unwillingly or indirectly – by our engagement with and our understanding of a collective European culture (the political expression of which is the European Union). Reading Dutch poetry, for example, is the process of interpreting how its points of convergence and divergence with your own country’s poetry reflect the way your two cultures communicate in the context of the larger political union. This is not a conscious decision, any more than reading French poetry was once necessarily intended to be a response to France’s political power. It is simply the international scenario that one is most likely to be confronted with when reaching outside of one’s own country, regardless of whether one subsequently chooses to embrace or resist it.

The European cultural register also defines our relationship with poetry from outside the continent. We understand a Korean poet or poem’s foreignness not so much to our specific country, but to European culture as a whole – even if it makes no sense to speak of this ‘culture’ as something unified. This is not as paradoxical as it may sound, because European culture in the sense that we are talking about it here is not unified, but unifying. If you are indeed able to read Dutch poetry, this will almost certainly be related to how this cultural union has connected you. (Our argument admits to several exceptions, especially when it comes to ex-colonies. The relationship of English readers to Indian literature, or that of French readers to Algerian literature, has its own special status).

In the current geopolitical context, one of the great victims has been English culture – and, by extension, English poetry. The rise of English as the ‘common tongue’ of the continent has excluded the British population from the surge of enthusiasm for multilingual studies which has filled the rest of the European soil with polyglots. The stupidity of English officials – who have seen this process happening for decades and have done nothing about it, even welcoming it as a blessing or a privilege – is mirrored by the stupidity of foreign European officials. A common continental lament may take a similar form: if the English tongue becomes dominant, then in a thousand years nobody will be able to read the books or listen to the songs that we are writing now, much like nobody can read some of the Gaelic or Celtic or ancient Hispanic inscriptions in caves dating from before the Roman (and Latin) invasion.

The oversight here is that languages do not have a half-life of a thousand years – they change spontaneously and ineluctably and become new systems of their own, in a process that is only bound to accelerate in the coming age. Since this mutability is the very source of beauty in language, there is no reason to lament it. And if you really are worried about how your poetry will be understood in 3012 (good luck to you, by the way), then rest assured – it will become illegible well before then, regardless of what language you are writing it in.

As for the present situation, almost every young educated person in non-anglophone Europe is at least bilingual, and sometimes much more than that. This means that Europeans born outside of England have more job opportunities and more academic outlets; they can travel to more countries, with all the openings for new learning and experience that that entails; they have access to more literature, music, art, journalism, criticism, ideas, as well as an instant advantage in anything related to politics, diplomacy, trade or tourism. The irony in all of this is that the ones who should be promoting anglocentrism are all non-English speaking countries, while the only ones fighting against it should be the countries in the UK. Instead it is the other way round!

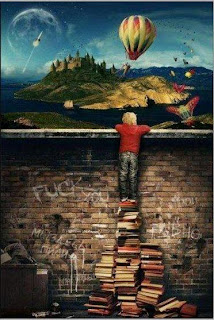

British poets are but one of the categories damaged by this development. Their burden is not only that a much greater workload is required to gain access to foreign poetry – for learning a foreign language becomes an enterprise, rather than a given – but the fact that they mature and develop into a culture unaware of its own anglocentrism. Scholars and poets desiring to branch outside the confines of their own country usually find themselves funnelled towards American poetry, and this inevitably leads to a sort of provincialism. As importantly, it blinds one to the realities of the European discourse as we have sketched it in this article. The common thread that runs across the various European nations, and which defines this moment of our cultural history, is distinctly weaker and harder to perceive here in England. And if this does not seem like a big deal, remember that missing out on a cultural shift is always your own loss. The Renaissance did not stop by for Russia. Classical music did not wait for the Americans. The mutual cultural integration of the European Union is not going to wait for English literature, unless English poets themselves go out and engage with it.

And this, of course, leads us to the next part of the argument: how do we approach international poetry? The second part of our article will be dedicated to the practicalities around this question. To be published as next week’s feature, still here on Drfulminare.com.