posted by the Judge

We’ve already had the chance for a chat with Kate Noakes in the past. She was pretty chuffed about it, at least judging by the photo we took after the interview (see above).

Now we’re taking it to the next level (ok, the football references are already overbearing) by reviewing her poetry collection Cape Town. The review was tackled (uh) by Shane A., who had never written for us before and is therefore kicking off, er, opening his career with us. The goal is to – ok I give up. Is it derby day or something?

Happy Sunday everyone!!

News

The Debris Field + Special Offers

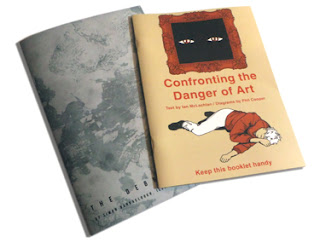

Sidekick Books’ latest publication, The Debris Field, is available now for £6 plus postage. It slots into our team-ups section, as it’s a collaboration between three poets: Simon Barraclough, Isobel Dixon and Chris McCabe, and a project which began (and continued) life as a multimedia performance with film-maker Jack Wake-Walker and Oli Barrett.

We’ve also got two special offers on the go. You can buy The Debris Field together with Simon Barraclough’s previous project (also featuring work by Dixon and McCabe), Psycho Poetica, for a combined price of £10 plus postage …

… or you can buy it together with our previous team-up pamphlet, Confronting the Dangers of Art, by poet Ian McLachlan and illustrator Phil Cooper for £8.50 plus postage.

Take advantage of either offer from the product page of any of the books.

On Clarity

What exactly do people mean when they demand, commend or recommend clarity in poems, and are they even referring to the same thing? Are we clear on what clarity is? I don’t think I am, even though I’m conscious of exactly what Randall Jarrell identified in the following quote, which I’ve thieved from a post by Tim Love on the subject of poetry and communication:

Interestingly, poets themselves do not present a united front against such reductionism. Some are scornful of attempts to resist clarity. Some treat it as a moral obligation. There seem to be several intermingling but subtly distinct rationales for this. The one I’ve encountered most is characterised by Adrian Mitchell’s famous proclamation: “Most people ignore most poetry because most poetry ignores most people.” When poetry doesn’t play fair, doesn’t make itself readily understandable and relateable, it is responsible for its own failure as a communicative medium.

But here’s where I tentatively come to the conclusion that accounts for my opening quizzicality: Mitchell’s complaint, when analysed, seems to have been not that there is too little clarity in poetry but that there is too much of it. I’m not kidding! Here’s how I’ve worked this out: I’m supposing for now that clarity means that the reader is able to almost instantaneously grasp the literal meaning and the implications of the poem he or she is reading or listening to. They understand the common usage of all the words involved, the relevance of any names mentioned and how to make sense of the sentence construction. More than that, however, they see how it all fits together. They find it a relatively simple task to intuit the intentions of the poet in writing the piece, and may even feel the faint thrill of a connection. The poem ‘speaks’ to them. It understands their condition as a human being, and addresses it. If the poem is particularly good, they might feel it achieves a state of being “what e’er was thought, but ne’er so well express’d”.

A crude example sometimes used by those in the Mitchell frame of mind is the ‘poetry nod’ that a supposedly snooty poet gets when his obscure classical reference is picked up by an equally snooty audience, the enjoyment being one of exclusivity. “I get it. Others wouldn’t. I’m in the club.” But this is a fallacy; the little sighs and nods that occur throughout intimate poetry readings are far more likely to be the result of an experience of clarity, where a phrase or line seems to have achieved a sublime level of meaning, where the channel of communication is suddenly exquisitely open.

Anyone who has ever discussed films or art or stories with friends knows that this kind of experience is uncannily, almost frustratingly subjective. We can turn to the person who has just sat through exactly the same two and a half hours of cinema with us and find that they were unable to follow the plot that we found almost simplistic, loathed the characters we found sympathetic and successfully predicted the twist that caught us completely off guard. This could be a person we know very well, someone who shares our interests, and as such we often find the difference in personal experience baffling.

Clearly, though, the way we react to art is not wholly a matter of unfathomable randomness. Different styles and genres can be marketed to different demographics with a fairly secure expectation of broad understanding and enjoyment. Collectively, we’re fairly good (but not brilliant) at working out what works for each other by reference to certain distinguishing traits, and unsurprisingly, many of us have a real knack for knowing how to effectively communicate with people who are … well, more or less exactly like us.

The poem-reader connection I describe above, therefore, is more than likely in each case to be attributable to something beyond what the words themselves are doing. The ‘clear’ poem is one expertly pitched to its target demographic – probably someone who thinks in a similar way to the poet, who can draw from similar experiences, for whom certain words have the same significance. That’s not to say, of course, that the poem can’t have a meaning or significance, even beauty, to anyone outside this narrow beam; just that it’s the most obvious explanation for the particular experience of clarity.

So if Mitchell deplored the writing of poetry that ignores the majority but is tuned specifically for a particular group, then, well, he was against the surest route to providing readers with that experience. The pursuit of clarity must surely involve that narrowing of focus. To write for ‘most people’ is to give the poem up entirely to that uncanny subjectivity that causes us to react in all manner of different ways. Even the most hopelessly ambitious marketing strategy sells the line ‘something for everyone’, not ‘the same thing for everyone’.

I would assume that most poets do not recognise ‘the few’ and ‘the many’ as a binary choice. Rather, they’ll attempt to keep in mind various possible readers while trying principally to please themselves. That is, the ultimate criterion they use is: “Would this poem speak to me, if I’d just happened upon it?” I don’t see anything wrong with this method, but the natural consequence, in most cases, is going to be a spread of reactions and personal experiences in the minds of the range of readers the poem may eventually reach.

Here’s where the difficulty really starts. In being fortunate enough to experience clarity while reading poetry, critics and commentators often discount the idea that their own particular qualities – the possibility of their shared interests and knowledge with the poet, for example – is a principle factor in that experience. When they subsequently demand, commend or recommend clarity, they’re really importing the idea that all (or most) readers are just like them.

I shouldn’t be surprised then (although in truth, I usually am) when their conclusions as to which poems ‘play fair’ and which are self-indulgently opaque differ wildly from mine. It’s not at all unlikely that the most sincere attempt to pin down a difficult truth – one that seems just beyond the scope of language – will fail in what it aims to do for most readers. It’s somewhat less likely that readers will be more receptive to such difficult truths than to something that they know they want to hear, something that has an affirmative aspect to them. How often are poets praised for ‘challenging expectations’ by readers whose hopes and expectations were happily fulfilled?

What should and does seem odd, then, is the importance attributed to sincere attempts towards clarity when the results of such attempts are so unpredictable. Odder still in a medium where many of the pleasures come from lack of clarity. Maybe I’m playing with words here, but I’m reflecting on the poems that first led me to take an interest in contemporary poetry. For the most part, I didn’t understand their literal meaning very well at all, and it was that that led me to notice more intently the texture and music of the language used, and to find pleasure there. I’m still not sure, when I look around at poetry audiences, how many really notice or care about texture or music, and how many are jonesing for their next hit of clarity – the next line that will tell them exactly what they’re hoping to hear. And if this is 90% of what poetry is to them, is poetry criticism fated to be muddied by expressions of the subjective?

The general public … has set up a criterion of its own, one by which every form of contemporary art is condemned. This criterion is, in the case of music, melody; in the case of painting, representation; in the case of poetry, clarity. In each case one simple aspect is made the test of a complicated whole, becomes a sort of loyalty oath for the work of art. … instead of having to perceive, to enter, and to interpret those new worlds which new works of art are, the public can notice at a glance whether or not these pay lip-service to its own ‘principles’ …

Randall Jarrell

Interestingly, poets themselves do not present a united front against such reductionism. Some are scornful of attempts to resist clarity. Some treat it as a moral obligation. There seem to be several intermingling but subtly distinct rationales for this. The one I’ve encountered most is characterised by Adrian Mitchell’s famous proclamation: “Most people ignore most poetry because most poetry ignores most people.” When poetry doesn’t play fair, doesn’t make itself readily understandable and relateable, it is responsible for its own failure as a communicative medium.

But here’s where I tentatively come to the conclusion that accounts for my opening quizzicality: Mitchell’s complaint, when analysed, seems to have been not that there is too little clarity in poetry but that there is too much of it. I’m not kidding! Here’s how I’ve worked this out: I’m supposing for now that clarity means that the reader is able to almost instantaneously grasp the literal meaning and the implications of the poem he or she is reading or listening to. They understand the common usage of all the words involved, the relevance of any names mentioned and how to make sense of the sentence construction. More than that, however, they see how it all fits together. They find it a relatively simple task to intuit the intentions of the poet in writing the piece, and may even feel the faint thrill of a connection. The poem ‘speaks’ to them. It understands their condition as a human being, and addresses it. If the poem is particularly good, they might feel it achieves a state of being “what e’er was thought, but ne’er so well express’d”.

A crude example sometimes used by those in the Mitchell frame of mind is the ‘poetry nod’ that a supposedly snooty poet gets when his obscure classical reference is picked up by an equally snooty audience, the enjoyment being one of exclusivity. “I get it. Others wouldn’t. I’m in the club.” But this is a fallacy; the little sighs and nods that occur throughout intimate poetry readings are far more likely to be the result of an experience of clarity, where a phrase or line seems to have achieved a sublime level of meaning, where the channel of communication is suddenly exquisitely open.

Anyone who has ever discussed films or art or stories with friends knows that this kind of experience is uncannily, almost frustratingly subjective. We can turn to the person who has just sat through exactly the same two and a half hours of cinema with us and find that they were unable to follow the plot that we found almost simplistic, loathed the characters we found sympathetic and successfully predicted the twist that caught us completely off guard. This could be a person we know very well, someone who shares our interests, and as such we often find the difference in personal experience baffling.

Clearly, though, the way we react to art is not wholly a matter of unfathomable randomness. Different styles and genres can be marketed to different demographics with a fairly secure expectation of broad understanding and enjoyment. Collectively, we’re fairly good (but not brilliant) at working out what works for each other by reference to certain distinguishing traits, and unsurprisingly, many of us have a real knack for knowing how to effectively communicate with people who are … well, more or less exactly like us.

The poem-reader connection I describe above, therefore, is more than likely in each case to be attributable to something beyond what the words themselves are doing. The ‘clear’ poem is one expertly pitched to its target demographic – probably someone who thinks in a similar way to the poet, who can draw from similar experiences, for whom certain words have the same significance. That’s not to say, of course, that the poem can’t have a meaning or significance, even beauty, to anyone outside this narrow beam; just that it’s the most obvious explanation for the particular experience of clarity.

So if Mitchell deplored the writing of poetry that ignores the majority but is tuned specifically for a particular group, then, well, he was against the surest route to providing readers with that experience. The pursuit of clarity must surely involve that narrowing of focus. To write for ‘most people’ is to give the poem up entirely to that uncanny subjectivity that causes us to react in all manner of different ways. Even the most hopelessly ambitious marketing strategy sells the line ‘something for everyone’, not ‘the same thing for everyone’.

I would assume that most poets do not recognise ‘the few’ and ‘the many’ as a binary choice. Rather, they’ll attempt to keep in mind various possible readers while trying principally to please themselves. That is, the ultimate criterion they use is: “Would this poem speak to me, if I’d just happened upon it?” I don’t see anything wrong with this method, but the natural consequence, in most cases, is going to be a spread of reactions and personal experiences in the minds of the range of readers the poem may eventually reach.

Here’s where the difficulty really starts. In being fortunate enough to experience clarity while reading poetry, critics and commentators often discount the idea that their own particular qualities – the possibility of their shared interests and knowledge with the poet, for example – is a principle factor in that experience. When they subsequently demand, commend or recommend clarity, they’re really importing the idea that all (or most) readers are just like them.

I shouldn’t be surprised then (although in truth, I usually am) when their conclusions as to which poems ‘play fair’ and which are self-indulgently opaque differ wildly from mine. It’s not at all unlikely that the most sincere attempt to pin down a difficult truth – one that seems just beyond the scope of language – will fail in what it aims to do for most readers. It’s somewhat less likely that readers will be more receptive to such difficult truths than to something that they know they want to hear, something that has an affirmative aspect to them. How often are poets praised for ‘challenging expectations’ by readers whose hopes and expectations were happily fulfilled?

What should and does seem odd, then, is the importance attributed to sincere attempts towards clarity when the results of such attempts are so unpredictable. Odder still in a medium where many of the pleasures come from lack of clarity. Maybe I’m playing with words here, but I’m reflecting on the poems that first led me to take an interest in contemporary poetry. For the most part, I didn’t understand their literal meaning very well at all, and it was that that led me to notice more intently the texture and music of the language used, and to find pleasure there. I’m still not sure, when I look around at poetry audiences, how many really notice or care about texture or music, and how many are jonesing for their next hit of clarity – the next line that will tell them exactly what they’re hoping to hear. And if this is 90% of what poetry is to them, is poetry criticism fated to be muddied by expressions of the subjective?

Coin Opera II preview at GEEK2013!

Along with debonaire compere Dan Simpson, on Saturday 23 February Sidekick Books will be taking a seaside trip to Margate to top games expo GEEK2013!

We’ll be performing a special preview of Coin Opera II: Fulminare’s Revenge, our second, and much expanded, anthology of computer games poetry. Expect epic Lemmings escape sagas, remixed Sonic and the tragedy of Pac Man’s orange ghost.

The Debris Field and ‘Out of the Debris’ event

Sidekick Books is very excited to announce that we will shortly be publishing the book to accompany multi-media poetry production and Titanic tribute, The Debris Field. Devised, written and performed by poets Isobel Dixon, Simon Barraclough and Chris McCabe, The Debris Field had its British Film Institute premiere in a sell-out show on 14 April 2012, the centenary of the sinking of Titanic.

Don’t miss the trio’s one-off performance on Thursday 21 February, ‘Out of the Debris’, at The Rich Mix, London. Alongside composer Oli Barrett and film-maker Jack Wake-Walker, Barraclough, Dixon and McCabe will present poetry, images and sound as ‘live cinema’. This is a rare chance to catch an immersive and haunting show.

For more info, and to buy tickets, go here: http://www.richmix.org.uk/whats-on/event/out-of-the-debris/

Facebook event here.

Don’t miss the trio’s one-off performance on Thursday 21 February, ‘Out of the Debris’, at The Rich Mix, London. Alongside composer Oli Barrett and film-maker Jack Wake-Walker, Barraclough, Dixon and McCabe will present poetry, images and sound as ‘live cinema’. This is a rare chance to catch an immersive and haunting show.

For more info, and to buy tickets, go here: http://www.richmix.org.uk/whats-on/event/out-of-the-debris/

Facebook event here.

Open letter to Maurice Riordan

Dear Maurice,

First of all, congratulations on becoming the new editor of Poetry Review. As an editor of numerous anthologies and a former submissions editor at Poetry London, it’s clear you’re well qualified for the position. I’m writing to you now because, after a period of wavering – and following encouragement from an editor of some standing – I applied for the position myself and, in the days following my application, started to think pretty seriously about what I would do if I were offered the job. The more I thought about it, the more I felt that the answers I was coming to represented not what elements of a personal style I would hope to bring to the journal but a deeper necessity for change, and so, rather than keep my powder dry for the purposes of another application years down the line (when who knows what will have transpired), I would like to outline those proposals now and ask you to seriously consider them.

The last three issues of Poetry Review, edited by George Szirtes, Charles Boyle and Bernadine Evaristo respectively, refreshed the feel of the journal enormously, and that project should be pursued under the new editorship. Importantly, I feel that Poetry Review must seek to shed the image of a publication aimed squarely at middle class readers of mainstream poetry. I’m aware that ‘middle class’ and ‘mainstream’ are vexed terms, often used pejoratively, but they have some valid application here. I’ve written previously about the elements of tribalism in British poetry, where mainstream sits in the centre, performance poetry and avant-garde poetry at either side of it. This is a crude delineation, of course, and there are many, many poets and many, many projects that straddle these imaginary boundaries. But am I wrong to infer, simply from reading and listening to a range of view points, that most poets who see themselves as working in the ‘non-mainstream’ area regard the modern Poetry Review as a territory they are all but barred from, while many who see their work as centered around performance regard it as almost belonging to (and promoting) a different medium?

Poetry journals are of course entitled to develop their own character and style, but I feel that there is room for at least one that aspires to carrying out the role of broad overview, creating a space where different poetries intermingle, and it seems fitting that it should be the publication of the Poetry Society. It is, after all, called Poetry Review, and it’s reasonable therefore to expect it to review the full breadth of poetry culture in the UK – and beyond, if necessary. My personal tastes do not stray too far outside of what is generally considered mainstream, (although I’ve been trying to get to grips with avant-garde work for some time) but I concluded, during my brief ruminations on what I would do with the editorship, that the editor should seek to go considerably beyond the boundaries of his or her personal taste, and take on the risk of betraying naivety in certain areas in order to ensure that the contents of each issue are somewhat representative of the full panoply of poetic endeavour. None of us know poetry well enough to stick to what we intimately know and not end up with a partial selection.

But I’m not just talking about the choosing of new poems which are published. In fact, I think that’s perhaps less important than the focus of the essays and reviews. George Szirtes’ issue included a piece on Denise Riley by Emily Critchley that was strikingly different to the character of the majority of pieces PR has tended to publish. I would like to see more pieces along these lines, but more importantly still, I would like to see pieces which explore and question the boundaries between different poetries, or articulate what underlying disputes there are as to the validity of certain approaches. Dialogue. That’s what I’m talking about. I would like to see Poetry Review as a platform for dialogue. Consider a poet like Anthony Anaxagorou, whose politically engaged poem If I Told You has amassed nearly 30,000 views online, and who has worked for the Poetry Society. It strikes me he’s not the normal type of poet Poetry Review would publish, and that If I Told You is not the type of poem that many poetry readers would normally rave about. It is political and somewhat of a polemic. Does this indicate a popular movement in poetry that is apart from what many of us are focused on? I think there is room for such a discussion. I certainly think there is room to acknowledge poetic achievements beyond the winning of centrally-administered prizes.

I mentioned ‘middle class readers’ earlier. I am very wary of making any pronouncement based on supposed class boundaries or stereotypes of certain classes. I am probably middle class myself, but some would call this self-aggrandisement, since I lack property, a high-flying career and a matching crockery set. (It would definitely be self-aggrandisement to call myself working class, since I went to university and my accent isn’t regional enough). I’m also a defender of the much-ridiculed ‘quiet’ poetry reading, where the audience are allowed to sit and entertain their own thoughts about the poetry being read, and success is not measured by the strength of vocalised positive reaction. Nevertheless, I think it’s fairly recognisable there is a large overlap between middle class concerns and mainstream poetry topics, such that we have to be vigilant against favouring certain poets and certain poetries because of how they meet our own expectations. I can’t describe or pin down that middleclassness precisely, because by its nature, it is more cumulative effect than anything that can be ascribed to the contents of one poem or book (although Sean Borodale’s Bee Journal must be near its epicentre). It is present, however, and it provides another reason for potential readers of poetry to close their minds to it, writing us all off as comfortable wine-swillers enthusing about our holidays abroad.

I think Poetry Review should be a point from which to challenge such negative perceptions, and never something which enforces or lends validity to them. I think it should be a place where radically different propositions can jostle with each other, and where readers might cross, in their droves, the strange boundaries between different poetries. I think it is reasonable and right that Poetry Review aims for a readership of such a mixture of backgrounds that no one, seeing the crowd of attendees at a launch night, could think that the journal had a core demographic at all, and where no one entering could feel that they have come to the wrong event. Of course, this won’t be an overnight change, but now is the opportunity to set it in motion.

Yours sincerely,

Jon Stone

First of all, congratulations on becoming the new editor of Poetry Review. As an editor of numerous anthologies and a former submissions editor at Poetry London, it’s clear you’re well qualified for the position. I’m writing to you now because, after a period of wavering – and following encouragement from an editor of some standing – I applied for the position myself and, in the days following my application, started to think pretty seriously about what I would do if I were offered the job. The more I thought about it, the more I felt that the answers I was coming to represented not what elements of a personal style I would hope to bring to the journal but a deeper necessity for change, and so, rather than keep my powder dry for the purposes of another application years down the line (when who knows what will have transpired), I would like to outline those proposals now and ask you to seriously consider them.

The last three issues of Poetry Review, edited by George Szirtes, Charles Boyle and Bernadine Evaristo respectively, refreshed the feel of the journal enormously, and that project should be pursued under the new editorship. Importantly, I feel that Poetry Review must seek to shed the image of a publication aimed squarely at middle class readers of mainstream poetry. I’m aware that ‘middle class’ and ‘mainstream’ are vexed terms, often used pejoratively, but they have some valid application here. I’ve written previously about the elements of tribalism in British poetry, where mainstream sits in the centre, performance poetry and avant-garde poetry at either side of it. This is a crude delineation, of course, and there are many, many poets and many, many projects that straddle these imaginary boundaries. But am I wrong to infer, simply from reading and listening to a range of view points, that most poets who see themselves as working in the ‘non-mainstream’ area regard the modern Poetry Review as a territory they are all but barred from, while many who see their work as centered around performance regard it as almost belonging to (and promoting) a different medium?

Poetry journals are of course entitled to develop their own character and style, but I feel that there is room for at least one that aspires to carrying out the role of broad overview, creating a space where different poetries intermingle, and it seems fitting that it should be the publication of the Poetry Society. It is, after all, called Poetry Review, and it’s reasonable therefore to expect it to review the full breadth of poetry culture in the UK – and beyond, if necessary. My personal tastes do not stray too far outside of what is generally considered mainstream, (although I’ve been trying to get to grips with avant-garde work for some time) but I concluded, during my brief ruminations on what I would do with the editorship, that the editor should seek to go considerably beyond the boundaries of his or her personal taste, and take on the risk of betraying naivety in certain areas in order to ensure that the contents of each issue are somewhat representative of the full panoply of poetic endeavour. None of us know poetry well enough to stick to what we intimately know and not end up with a partial selection.

But I’m not just talking about the choosing of new poems which are published. In fact, I think that’s perhaps less important than the focus of the essays and reviews. George Szirtes’ issue included a piece on Denise Riley by Emily Critchley that was strikingly different to the character of the majority of pieces PR has tended to publish. I would like to see more pieces along these lines, but more importantly still, I would like to see pieces which explore and question the boundaries between different poetries, or articulate what underlying disputes there are as to the validity of certain approaches. Dialogue. That’s what I’m talking about. I would like to see Poetry Review as a platform for dialogue. Consider a poet like Anthony Anaxagorou, whose politically engaged poem If I Told You has amassed nearly 30,000 views online, and who has worked for the Poetry Society. It strikes me he’s not the normal type of poet Poetry Review would publish, and that If I Told You is not the type of poem that many poetry readers would normally rave about. It is political and somewhat of a polemic. Does this indicate a popular movement in poetry that is apart from what many of us are focused on? I think there is room for such a discussion. I certainly think there is room to acknowledge poetic achievements beyond the winning of centrally-administered prizes.

I mentioned ‘middle class readers’ earlier. I am very wary of making any pronouncement based on supposed class boundaries or stereotypes of certain classes. I am probably middle class myself, but some would call this self-aggrandisement, since I lack property, a high-flying career and a matching crockery set. (It would definitely be self-aggrandisement to call myself working class, since I went to university and my accent isn’t regional enough). I’m also a defender of the much-ridiculed ‘quiet’ poetry reading, where the audience are allowed to sit and entertain their own thoughts about the poetry being read, and success is not measured by the strength of vocalised positive reaction. Nevertheless, I think it’s fairly recognisable there is a large overlap between middle class concerns and mainstream poetry topics, such that we have to be vigilant against favouring certain poets and certain poetries because of how they meet our own expectations. I can’t describe or pin down that middleclassness precisely, because by its nature, it is more cumulative effect than anything that can be ascribed to the contents of one poem or book (although Sean Borodale’s Bee Journal must be near its epicentre). It is present, however, and it provides another reason for potential readers of poetry to close their minds to it, writing us all off as comfortable wine-swillers enthusing about our holidays abroad.

I think Poetry Review should be a point from which to challenge such negative perceptions, and never something which enforces or lends validity to them. I think it should be a place where radically different propositions can jostle with each other, and where readers might cross, in their droves, the strange boundaries between different poetries. I think it is reasonable and right that Poetry Review aims for a readership of such a mixture of backgrounds that no one, seeing the crowd of attendees at a launch night, could think that the journal had a core demographic at all, and where no one entering could feel that they have come to the wrong event. Of course, this won’t be an overnight change, but now is the opportunity to set it in motion.

Yours sincerely,

Jon Stone

Sunday Review: Morgan Harlow’s Midwest Ritual Burning

posted by the Judge

Well, here we are once more. It’s Sunday, and like all Sundays, we’re cramming the trunk with beer-packs and setting off for Somerset, where we shall visit the grave of King Arthur in Glastonbury.

No hold on a second. That’s for the blog on ancient rituals behind beer. What happens here is that we have a poetry review, one which you can read by clicking on this particular link. Morgan Harlow wrote a collection called Midwest Ritual Burning, referring to the fact that she kept burning her fingers whenever she was a kid and they had barbecues (the cover for the book, with the original title, is displayed above). Anthony Adler, our reviewer for the day, was actually supposed to review some of my own work, but he got back to me telling mehe’d rather gouge his eyes out than plod through my bull he was very keen on doing Morgan, so he’s back to the reviewing boards.

Have a great Sunday!

Well, here we are once more. It’s Sunday, and like all Sundays, we’re cramming the trunk with beer-packs and setting off for Somerset, where we shall visit the grave of King Arthur in Glastonbury.

No hold on a second. That’s for the blog on ancient rituals behind beer. What happens here is that we have a poetry review, one which you can read by clicking on this particular link. Morgan Harlow wrote a collection called Midwest Ritual Burning, referring to the fact that she kept burning her fingers whenever she was a kid and they had barbecues (the cover for the book, with the original title, is displayed above). Anthony Adler, our reviewer for the day, was actually supposed to review some of my own work, but he got back to me telling me

Have a great Sunday!

Glyn Maxwell’s ‘On Poetry’ (Part 2 of 2)

in which the Judge continues the argument he started last week.

Maxwell opens his book with a promising discussion on evolutionary psychology and the way that we process and appreciate images and symbols. It is an anthropological outlook on poetic studies – one which could yield a great deal of results. Unfortunately, he abandons it almost right away in favour of his ‘primal’ discussion of the black and the white. This is a pretty transparent attempt at festooning his theory with a little bit of scientific legitimacy. It is sad, because he is going the wrong way round: he would probably find more fertile ground if he took a scientific approach to his aesthetic categories, rather than an aesthetic approach to a scientific idea. The latter is best left to poetry – using it in criticism only seduces the reader without actually revealing anything about the subject matter at hand. Indeed, the only thing that you can learn from this type of criticism is how the author thinks (which is enough of a reward with thinkers like Eliot or Calvino, and which was certainly enough for me when looking into a poet I admire as much as Maxwell). On Poetryis most interesting when Maxwell chronicles his own attempts, his own failures and successes, in his approach to the art. At those points you really learn a lot. For the rest of the time, however, there is little that comes with a sense of permanence. Today, nobody uses the word ‘classic’ in the sense that Eliot did. When reading On Poetry, you can never quite get rid of the feeling that even though Maxwell’s words are very pretty, no-one will ever use them if not in circumstantial exchange (“Oh, this reminds me about that wonderful book by Glyn Maxwell, he said something about pulse”…). This is necessarily the case, because they are not useful; and they are not useful because they are not true. By the time I reached the final chapter, ‘Time’, and found out it was entirely written in verse, I decided there was no point in bothering with a review and I closed the book.

On Poetry is a good book. It’s enjoyable and written with gusto and verve. But it’s certainly not the best book on poetry I have ever read (I’m picking on you, Newey – sorry), for the simple reason that it’s hardly about poetry at all. What it is, is a frolic. It’s a little exercise in form that only an established writer / poet can get away with (because the only thing that makes it interesting is what it reveals about the author). It could stand neatly in a library next to, say, Margaret Atwood’s Negotiating with the Dead. But it is also a book that loves to dress up. It wants to look like it’s bringing new ideas to the table, like its approach is fresh and original. And it’s all the more disappointing that there should be nothing new or original in this book because new concepts and possibilities in criticism areemerging, and there are so many things that we could learn from them.

The trouble with the circularity of literary criticism – i.e., having no means other than the poetic ones to describe poetry – is one that has on occasion been transcended. In the nineteenth century, psychoanalysis and Marxism pointed the way to new methodologies for reading literature. These schools have opened new doors for us in ways that more ‘poetic’ studies of literature (the preface to Wordsworth and Coleridge’s Lyrical Ballads, Poe’s The Poetic Principle, Baudelaire’s The Painter of Modern Life) could never dream of doing.

Today – and this is where I stray away from Maxwell’s book and why I didn’t want to write this as a review, but then I said that’s what I’d do, didn’t I? – we are faced with new concepts and ideas that have the same potential to open new doors for criticism. This isn’t the place for a rigorous enumeration of them, but off the top of my head, I might start with the school of cognitive poetics, which has revolutionised our idea of how ‘beauty’ is attained by studying the effects of poetry on the brain. Then there’s the fact that texts are now being uploaded digitally, which allows for an exponentially faster process of cross-reference. A group of scholars (whom I was, alas, unable to trace down) used this to find the ‘signature’ of famous writers, the traits and memes that generally identify someone like Jane Austen or Gustave Flaubert, and this allows us – among other things – to study their real effects on other writers by finding out where these patterns have been picked up again and recycled. And since I mentioned a meme, I should say a word about memetics – if only because Maxwell does borrow a memetic framework for some of his arguments, but – again – I would argue that his treatment is superficial and appropriative. Memetics is the school of thought according to which ideas develop according to the same evolutionary principles as genes; the applications of such a concept to the world of literature – if done rigorously, with a proper mathematical model behind them – would be endless. And since I mentioned maths, it is only recently that small attempts at using the formidable means of mathematics in the study of literature are being made, and this too links with a digital study of literature (the first, tiny fruits are coming out).

Things such as these, and not a vague reference to anthropology, give twenty-first century criticism the potential to truly renew our understanding of poetry. Some of it may sound like a fantasy, or even semi-blasphemous – I’m sure someone will call me a positivist or something for suggesting that mathematics may be used in understanding literature – but I’m not suggesting that new methods such as those I outlined above should supplant more traditional forms of criticism. There is the space for new ideas and established methods to coexist in harmony, especially in the humanities. The problem is that for a book such as Maxwell’s, it is dishonest to flirt with apparently unorthodox critical approaches (such as the ‘scientific’ backdrop of anthropology and evolutionary theory) and then be remiss to actually use them. Things have changed enormously in the last few decades and we have many new means of studying literature – Maxwell is employing none of them. In fact, his own means are no different than those used by Aristotle twenty-five centuries ago – except that Aristotle understood the need for rigour. To the best of his ability, Aristotle investigates – he never tries to seduce. Maxwell may not be expected to write a text comparable to the Poetics, but precisely for that reason he could at least try doing something different.

One final note in closing – and this isn’t strictly necessary, but I can’t help myself. Here’s a line from the back cover, detailing one of the things that Maxwell does in his book:

He speaks of his inspirations, his models, and takes us inside the strange world of the Creative Writing Class, where four young hopefuls grapple with love, sex, cheap wine and hard work.

Usually, the blurb behind the book throws around hyperbolic adjectives to encourage us to find out more about apparently dull subjects. You will find the memoirs of someone who worked in the ‘fascinating realm of space engineering’, or a novel set in the ‘mysterious alleyways of Paris’, or some pop science about the ‘revolutionary field of nanotechnology’. So I think it’s a sad measure of just how mind-numbingly boring some circles of poetry have become that even the editor couldn’t find any more exciting term to describe the setting than ‘the strange world of the Creative Writing Class’ (assuming it can even be called that – the only ‘strange’ thing about those classes I can think of is that they involve writers paying their readers, rather than the other way round). And I can overlook the fact that Maxwell’s description of the interactions between these four jocks is a collection of clichés, though I often wonder at older men who look at university students and assume they’re having casual sex every minute they’re not in a classroom (that, or I must have studied at the wrong universities). I’m not saying that everyone has to be Lord Byron, but really – have we come to the point of thinking that a Creative Writing class is a subject worth writing about? Then perhaps a book on poetry that is not actually about poetry really is the only type of product we deserve.

Sunday Review: James Brookes’ Sins of the Leopard

posted by the Judge

Sunday again, and I’ve just got time enough to post this review before I pack my bags (I’m moving to Birmingham). I am reviewing ‘Sins of the Leopard‘ by James Brookes. It’s a stupendous book, and the sins of the leopard are of course those of bad taste in dress and the use of foul language, which leopards famously indulge in (see pic).

The collection was actually supposed to be entitled ‘Since there’s a Leopard‘, in reference to the fact that Brookes used to work right outside of a zoo and was unable to write because the big cats kept mieowing, but apparently it was changed into the catchier ‘Sins of the Leopard‘ by his editors. I have no idea how they’re going to edit his upcoming second collection (‘That gelatinous platypus‘), but I’m sure they’ll come up with something equally good.

Seriously though. This collection kicked my ass. If you’re not going to read the review, do yourself a favour and read the book.

Have a great Sunday!

Sunday again, and I’ve just got time enough to post this review before I pack my bags (I’m moving to Birmingham). I am reviewing ‘Sins of the Leopard‘ by James Brookes. It’s a stupendous book, and the sins of the leopard are of course those of bad taste in dress and the use of foul language, which leopards famously indulge in (see pic).

The collection was actually supposed to be entitled ‘Since there’s a Leopard‘, in reference to the fact that Brookes used to work right outside of a zoo and was unable to write because the big cats kept mieowing, but apparently it was changed into the catchier ‘Sins of the Leopard‘ by his editors. I have no idea how they’re going to edit his upcoming second collection (‘That gelatinous platypus‘), but I’m sure they’ll come up with something equally good.

Seriously though. This collection kicked my ass. If you’re not going to read the review, do yourself a favour and read the book.

Have a great Sunday!

Poems in Which

Jon and I have poems in the latest issue of new poetry magazine Poems in Which. The concept is simple but fantastic. Remember all those poems that begin in this way? So do editors Amy Key and Nia Davies.

The manifesto for PiW reads:

Poems In Which is an occasional poetry journal edited by Amy Key and Nia Davies. Poems published here share a common title, ‘Poem in Which’ and they must be new, written for this journal, rather than post-titled to fit. Beyond that there are no constraints, nothing is true, everything is permitted.

As a challenge, writing a piece along these lines was at the same time was a free but focused experience. Given those three words as a kick-off, your brain immediately starts building scenarios. I worked with three possible titles before hitting upon ‘Poem in which I am captured. Again.’, and in the end I wrote something out of character/voice, which is always mighty satisfying.

Check out issues one and two here!