To start us off on our discussion, I was very interested by this remark made by CERN Director General Rolf Heuer made in reference to their inaugural Artist in Residence programme, “Particle physics and the arts are natural partners, both explore our place in the universe and both examine what it is to be human.” I think largely we do explore research topics with the view to elevating the grand enterprise of the expansion of human knowledge, but do we also have to have an element of soul-searching, and in order to do so, do we have to be ignorant of fact?

Hey Harry,

As far as I can see, the compulsion for expansion of human knowledge is the inherent consequence of soul-searching. As is argued in a book I read recently called ‘Truth or Beauty’ by David Orrell, from the very beginning of the study of natural sciences, as it grew out of the study of philosophy, the idea of an indivisible item in nature – Democritus’ atom – has been a prevailing and powerful aesthetic. Mary Midgely puts it very well in her book ‘Science and Poetry’ when she says that science has, “an unbalanced fascination with the imagery of atomism – a notion that the only way to understand anything is to break it into its ultimate smallest parts and to conceive these as making up something comparable to a machine.”

I think this want for finitude, purity and symmetry reflects a basic human want for the knowable. If nature is knowable, I am knowable.

I recently watched an extract from a fantastic documentary about Richard Feynman, ‘The Pleasure of Finding Things Out’, in which Feynman was talking about a discussion he had with his friend, an artist. The artist criticised Feynman for, as a scientist, taking the awe and beauty out of a flower by deconstructing it and making it into “a dull thing”. But Feynman argued that the deeper facts about the flower; the processes on a molecular level, the complicated actions of the cells, the evolutionary progressions that went into influencing the attractive colour of the petals, served only to add to the mystery, wonder and beauty of the flower.

I think any idea that science and art contradict each other essentially only underestimates the absolute astoundingness of the universe. So no, I don’t think we’re better off being ignorant of technical understanding. Like Feynman, I encounter a great “pleasure in finding things out”. But, not having a mathematical mind, and not having a formal scientific education (at least since yawningly timing ball-bearings as they rolled down a cardboard ramp and messing around with Bunsen burners), it is true my attempt at grappling with physics is conceptual at best. But the way my brain feels as it tries to expand out into our galaxy, into a million galaxies, or shrink into a single atom, the way it resists and bends spectacularly like light round a black hole, I find that feeling inspiring without an explicit understanding of the numbers. What do you think?

In the same documentary, Feynman is asked why magnets repel each other and he has great difficulty with the phrasing of the question – ‘why’. He says: ‘I really can’t do a good job, any job, of explaining magnetic force in terms of something else you’re more familiar with, because I don’t understand it in terms of anything else that you’re more familiar with.’ Does this suggest that metaphor is, as you were saying, an inadequate device when it comes to describing science? Or does this open up a challenge and a possibility for the poet?

Hi Ella,

That’s right, I think perhaps the two (the metaphysical – the soul searching, and the concrete, the fact) are immiscible only in so far as, and to borrow Ted Hughes’ phrase, they seem “like different stages of the same fever.”

Casting your line into the water and remaining mesmerised and excited by your subject, (sometimes referred to as the “poet’s trance”) often starts out as either a short phrase, or a set of parameters that are really just play in the truest sense, and this is accompanied equally by an insight.

When speaking to contemporary mathematicians and scientists, and listening to interviews with those at CERN or the MIT team responsible for the Apollo guidance computer in the 1960s and very early 70s, the language is very similar – “insight” and “play” – very much so Feynman’s words too – although the disciplines and applications are fundamentally different.

To expand a little on the kind of “insight” I mean, when I talk about insight in the context of the poetic mode, it is a kind of conjecture, a glimpse through the camouflage, the horror-film’s sudden loss of phone signal, or Eliot’s bird whom we are enticed to follow further into the rose garden of the poem’s unfurling. It is more delicate than merely the narcoleptic pianist, casting the a dissonant hotchpotch of notes with his head until the audience rise in a murmuration of subdued panic as the realisation dawns that this is no longer part of the concerto (although certainly the poet’s trance does sometimes fail spectacularly like this even though it’s given fewer column inches than more successful, hyperkulturemic – Romantic – attempts). The insight at the point of composition is a very fast-moving and fragile sense of what will come to unify the poem in terms of its tone or its lexicon. So insight in poetry is a very nebulous thing.

To “play” as a poet is less nebulous; play is often play in a very literal sense (pun intended) – I once input text from Pride and Prejudice into a conversation between customer service chatbots online to create a pantoum. Ozymandias was born from a similar poetry exercise between Horace Smith and Shelley and contemporary examples can be found in abundance in online writing forums and journals such as Like Starlings. When we play with ideas in a poem, we are experiencing a very great freedom – one which is either private as a dream, or something we wish to share, either way it is an agitation, an excitement of some kind, the lifting in the gut you get from fast, fresh air when leaping into the ocean. It should be said that this isn’t as Romantic as might be inferred – they are symptoms of neurological events rather than Divine wind.

In practice, of the poems that I write, the ones that are most often asked about at readings and remembered are those that have been derived from a matrix of strict rules. When writing about Scott Carpenter’s Aurora 7 mission which was the second manned mission in orbit conducted by NASA in 1962, designed to conduct atmospheric tests, I waded through 300 pages of mission logs and press releases to isolate pieces of information that intersected along the axiom of least distanced language and as you say the Carl Sagan-esque “astoundingness of nature” (lovely phrase). It was also grounded in a rucksack-destroying reading list of space programme research and the reason, experiment and result of the flight. Once I’d set myself these rules, I set more restrictions which were to craft the poem into quatrains and to create QR codes that linked through to archived photographs of the flight, allowing smartphone-equipped readers to look out of the capsule’s porthole over the Earth as they read the poem.

Even in moments where a tenable grasp of the language or where fact is less apparent, the context at least, is instant. The reading speed is slowed, allowing the scientific observations and emotional units to come to rest gently in the white page surrounding the poem. In a poem, the imagination adores a vacuum.

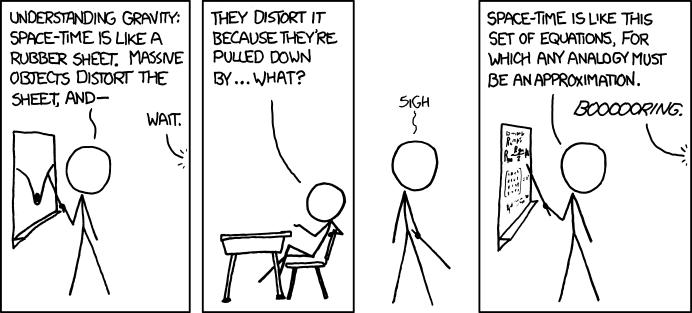

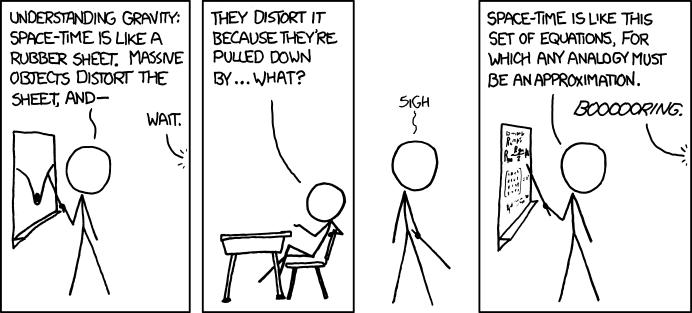

This is true too of the metaphor, where the semantics and calculation and specialist knowledge are too hard to convey within a short space, then the metaphor becomes a kind of shorthand, a mnemonic technique to engage the senses and consign the essential principles to memory. Dr Jocelyn Bell Burnell (a hero of mine) in a discussion on In Our Time (24/11/2005) about the graviton describes the curvature of space-time as being “like a rubber sheet” and the snooker ball of the Earth on the rubber sheet is pushing down on it and bending space-time and the analogy is very immediate. We might not have read Einstein’s 1905 article on the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies which landed him in the Encyclopaedia Britannica in 1911, and outlined the nature of space-time in the context of scientific learning or practical experiment or the interpretation of collected data, because as literature professionals, we tend to stick to our subject: poetry. Far more likely is that we’re familiar with its cultural cameos from The Big Bang Theory to the likes of T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets and Burnt Norton or Glyn Maxwell’s book, ‘Time’s Fool’, or in popular culture, films such as Primer and that I expect you probably tackle the subject in more detail your new book. In either discipline (literary or scientific) it would be facetious to imagine the circumstances under which we might be playing a round of snooker on the rubbery surface of space-time, because outside of episodes of Red Dwarf, we’re almost universally unlikely to have had experience of such a game. Nevertheless the general principle is clear, and the result – that this curvature warps light, and gravity around us – is easier to consider in those terms. Perhaps there is a simpler analogy or metaphor out there, which is down to us to synthesise.

In the sense that the general principle is more important to grasp than the atomized understanding, the proof becomes more of a footnote. It is problematic not least because such ventures often result in an awkward reductio ad absurdam such as Schrodinger’s Cat. The cat is both alive and dead – another implausible situation. Schrodinger’s cat is less of a metaphor (analogy really) and more of an allegory about the marriage between the classical world and the subatomic world, theEuclidian geometry of the dimensions we can observe with the naked eye, and the unobservable world we have to echolocate through high powered electron microscopes, particle accelerators, radio telescopes, or the probabilistic truth based on observed principles. For a lot of particle physics, it is the mathematics that suggests what ought to be investigated next through experiment. The theory can then be proven via strict methodology and peer review. Science is the business of aiming for the truth, even if ultimately the desired truth is never found, but something else is discovered along the way.

CERN is the place where the precise overlap between the classical world and the subatomic is being revealed. I think you express that in your poem “Black Hole” very deftly by having the two languages of song lyrics that are hypermetric, interspersed with explanations about the nature of black holes and referring to Stephen Hawking’s famous equation that seems to suggest that matter is becoming lost from the known universe permanently through black holes (apparently in violation of the second law of thermodynamics – that energy and matter are transformed, rather than lost).

“I write cheques / is there information loss? Is there information loss?”

Lavinia Greenlaw, who is a former Science Museum poet in residence, talks about this problem between the scientific metaphor and the poet’s role within it in an interview with the New Scientist, here. Both the classical world and the subatomic, are talking at cross-purposes on the same subject which is something that as poets we ought to be sensitive to. Hopefully the poem will then provide discoveries with an entry point into our vernacular, our language and broader cultural understanding.

I was wondering which poets you take as your touchstones, and so serve as influences or are hidden gems? And it would be great to know perhaps some of your favourite scientific analogies?

Harry

**

Hi Harry,

Yes, ‘like different stages of the same fever’ is a fantastic way to put it.

It’s very interesting what you are saying about insight and play. Your poetry is filled with a spirit of playfulness; I absolutely love your Pride and Prejudice / chatbot poem, and your poem ‘Earth’ which combines the familiar structure and language of social media with geological and prehistoric facts about the Earth.

Insight can provoke play and play can also provoke insight. I often find when I learn about a new scientific concept through research and reading that I have the impulse to experiment with it, to push the limits of its possibilities. In poems like Quantum and In This Double Split Experiment I Am In All Places At Once I take quantum principles and apply them to the everyday, a nonsensical practice in scientific reality, but a playful comment on how concepts such as an electron existing in all places at once can be both counter-intuitive and a familiar experience of the human mind where, for a double take, the back of every stranger’s head belongs to your ex. If you’re interested in quantum psychology, I’d recommend Roger Penrose’s book ‘Shadow of the Mind’ in which he argues that artificial intelligence in computers is impossible through classical Turing computing alone, and a new computing that allows quantum processes must be created in order to achieve AI. Much of the book concerns Penrose’s controversial theory that uninterrupted quantum activity is possible in the cytoskeleton of neurons in the brain, and Penrose suggests that this may be the source of consciousness. It’s an incredible read and, though now a bit outdated, it demonstrates an ambitious attempt to draw new connections between different sources of knowledge and different ways of thinking, opening up new areas of research. Mathematical patterns in nature have been of particular interest to me lately. My poem The Golden takes as its subjects various features of nature whose organisation can be explained through mathematics – the movement of starlings, the shape of a shell, bubbles, trees. But the main experimental impulse behind the composition of this poem was to use the Fibonacci sequence of numbers as a guide for syllable count per line. It is interesting to see to what extent this ‘magical formula’ built into almost any naturally-occurring shape or characteristic can or cannot improve the metre, sound and aesthetic of words. To how many degrees our language has been removed from the object it describes. I know you have also dabbled with the Fibonacci sequence in poetry and would love to hear more about that.

On reading your science poems, one simile that really stuck with me was the description of the spacecraft from ‘The First American in Space’: “The view from inside a marshmallow / in a camp fire, all blue and hot”. This image epitomises the ‘playful’ in that it is whimsical whilst encapsulating the shape, colours, and heat of both objects. It effortlessly captures the cosmological macro world unfolding into the personal, anecdotal micro realm, unfolding into the atomic, this seemingly vertiginous, boundless fall which follows the question ‘why is there something rather than nothing?’ Much like a Jackson Pollock drip painting, which harnesses the power of fractals (a small part of it looks the same as the whole), something deep within us can’t believe that pi’s infinite sequence of numbers can simply be arbitrary.

This leads me to your question about scientific analogies. It could be argued that subatomic particles themselves are an analogy. The realist might suggest that findings at CERN represent real physical snooker ball-type objects smashing each other apart and crashing into detectors. But many instrumental theorists view particles as simply a convenient fiction. What may seem to be an electron is, in reality, an excitation in the quantum electromagnetic field. The great mystery of wave/particle duality finds its solution here. I guess this fits neatly with what you were saying about CERN – here is where we will find exactly at what point our Euclidian language can no longer articulate subatomic activity.

The “bee in a cathedral” analogy is another that immediately springs to mind. This is used to explain the proportions of an atom – that if an atom were the size of a cathedral, the nucleus would be about the size of a bee. This strikes me as more of an effective analogy than most because it is exactly clear what each component of the analogy is supposed to represent – the walls of the cathedral are the extent of the areas where the electrons will be, the bee is the size of the nucleus. I was lucky enough to have Lavinia Greenlaw as my supervisor whilst I was writing my poetry dissertation and something she often expressed was the importance of analogies and metaphors in poetry to be absolutely precise. Each component of the metaphor must be measured against the others, to rigorously test its sense. This is what makes writing them so difficult. And when it comes to science, it’s all in the details.

But I think Heidi Williamson (who was also poet in residence at the Science Museum) achieves a beautiful analogy in the first poem ‘Slide Rule’ of her incredible collection ‘Electric Shadow’:

“The universe is running away with itself

Like a child on a red bike on Christmas Day.

Somewhere the wrapping is still being opened.

The present gives itself again and again.”

She links the cosmological to the personal and, in the same way a child has the impulse to move forward, not with destination in mind, but simply for the impulse of moving, as does the universe.

Poets that I feel have a big influence on me currently include Lavinia Greenlaw, Paul Farley, e e cummings, Michael Ondaatje, Elizabeth Bishop and Tim Lilburn (I like to think of Lilburn as a hidden gem, since you ask, and urge you to get hold of a copy of ‘Desire Never Leaves’.) But Jorie Graham’s poetry, particularly ‘PLACE’, has probably had the biggest impact on me in my most recent reading, hers is the kind of writing that’s made me realise what can really be done with language. I read the poem ‘Mother and Child (The Road At The Edge Of The Field)’ on a day in mid October on the metro in Manchester and I remember exactly where the train was, between Trafford Bar and Cornbrook, when I finished the poem and had the overwhelming sensation, (in the horror movie version of this story my phone just lost signal) a jolt that brought me out of the quotidian and onto an Earth that I intellectually acknowledge but rarely feel a part of.

Jorie Graham is often called a nature poet as much of her poetry is located in the natural world and PLACE in particular is concerned with the destruction and devastation that humanity is currently wreaking on the planet. You mentioned that you wondered if poets should have a certain responsibility to spread awareness of scientific discovery and catastrophe and I believe that Graham would argue they should. Graham’s writing is deeply scientific – she depicts not only the processes that exist deep in every natural form but also their shimmering fragility. These are not poems of generality about the sublime in nature, but specific and precisely informed. Her original use of line length, often very long lines followed by three or four very short lines, and mastery of a compulsive, prolonged syntax tenderly set up image to image like an organic flow which is being pressed against, tested by human intellect and ownership:

“..and I talk to myself, I make

words that follow from other

words, they push from be-

hind – into the hedge like the

hedge but not of it-no-not

ever-slippery against it where it

never knows they are pressing”

Some subjects seem too massive to comprehend, literally – the universe, (or even too miniscule – imaging a bee in a cathedral may help us perhaps get somewhere near to understanding atomic proportions, but can any human accurately imagine the tininess of the Planck length?) and also sometimes too removed from our lives. One of these things is the genuine threat of global warming. Graham’s words, where many other mediums have failed before, made me feel both rooted in a world tipping dizzyingly on the edge, and urgently arrested.

Who are your favourite poets / your influences?

Ella

Hi Ella,

Whenever I read your emails I get very excited and immediately think, “Of course! We should talk about x” and then I vanish off into a hinterland of old books and drafts. I would love to get back to you about Penrose – I read the prequel to that book which is ‘The Emperor’s New Mind’ – in which he proposes that time runs backwards in the brain, but I think we probably ought to leave that for when we next see one another!

I worked on a handful of Fibonacci poems that share the number of words per line with the Fibonacci sequence (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8 and so on) looking at how popcorn explodes in a microwave. For those that aren’t familiar with the Fibonacci sequence, the numbers are found by starting with 1 and 1, then 2 as above and then adding the two preceding numbers, so 2 and 1 becomes 3, 3 and 2 becomes 5 and so on. The relationship to the Golden Ratio is where you divide one number in the sequence by the number that precedes it. The higher up in the sequence you go, the more accurate the Golden Ratio number which eventually becomes 1.618033 and stretches on into infinity. This ratio of 1:1.618 is the number that governs the symmetry in the division of cells, to the number of clockwise to anti-clockwise seeds on the face of a sunflower, to the proportions of a good photograph or portrait painting. For that reason it was called the Divine Proportion by the Ancient Greeks. More information is available on it here.

So, I’m very jealous of you having had Lavinia Greenlaw as a tutor, and it’s certainly her name that seems to be most associated with poetry that addresses science most directly, although, as you say, Heidi Williamson‘s poetry, too, is startling and I’ve recently bought a copy of ‘Electric Shadow’ and have been unable to go anywhere – it seems – without it. I haven’t read Jorie Graham or Tim Lilburn, but I look forward to getting stuck in.

Speaking of influences, right now I’m reading more poems than poets specifically (thinking of Edwin Morgan’s The First Men on Mercury and Alice Oswald’s A Sleepwalk on the Severn – which returns again and again to the Moon, its silences and its passivity to light and the goings-on of Earth). Heidi Williamson’s ‘Cosmonaut‘ and Lavinia Greenlaw’s ‘For the First Dog in Space‘ touch thematically on the appalling level of risk involved in the early days of space travel. One story that always stays with me is that of the re-entry of Soviet cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov. Following the failure of one of the Soyuz’s ion engines, Komarov spends five hours attempting to orientate his craft for a manual re-entry. Believing that his death is a foregone conclusion, his wife is summoned to the Baikonur control room. Via a crackly video link that keeps shorting out because of the lack of power to the cabin, they discuss how they will bring the news to the children and the two finally say their goodbyes to one another.

With brilliant piloting skill and against all odds, Komarov is able to manoeuvre – by hand – the Soyuz 1 capsule through piercing exospheric sunlight into the correct orientation for re-entry. Then there is radio silence. Ionised air blasts the surrounding metal of the capsule and the pink, green and orange aurora of 10,000 degree heat is clearly visible just three feet away from his face. In the control room all that is audible is a long, ominous, static drawl. The control room calls and calls and calls “Rubin, this is Zarya, how do you hear me? Over. Rubin, this is Zarya, how do you hear me? Over. This is Zarya, how do you hear me? Over ….”

There is no response.

After five long minutes, the signal comes through to the ground that Soyuz 1 has successfully re-entered the atmosphere and is 60km outside Orsk, near the Kazakhstan border. However, this is not where the story ends. High up in the atmosphere, Komarov has pulled a switch to deploy the drag parachute to slow his descent. Without the drag parachute he would be travelling so fast that his main capsule parachute would sheer off. The drag chute spools, juttering out behind him and inflates successfully. He is still travelling at formidable speed, so much so that it takes him five seconds to drop 10,000ft. He pulls the lever to deploy the drogue parachute. This drogue chute is designed to act as a primary air brake, and will allow the capsule to slow to non-lethal speed. It fails. Again, all is not lost as the reserve chute inflates for a few seconds, however it quickly becomes tangled with the drag chute. The capsule accelerates, hurtling uncontrollably toward the ground, ultimately, tragically sending him careening to his death. So when writing about the flight of Alan Shepard, the first American in space, I think of how likely it was that he could have met his end at any second and that is still something that makes my stomach flinch.

To close our conversation down a little (I’m sorry), and to pull together some of the threads we’ve been pursuing. I think we do enter into a kind of pact the minute we use scientific terminology and negotiating between what to tell and what to leave to the imagination. In a lot of ways it does come close to the phrase I used at the beginning to kick off our discussion — that particle physics and the arts are natural partners in expressing “what it means to be human”. I love your poem In This Double Split Experiment I Am in All Places At Once and that thought that “subatomic particles themselves are an analogy”. In your poem I think we have to keep the idea in mind that either the speaker or the words as objects or the meaning of those words are in superposition with one another. In a very literal sense, they are, the black words on the white page, and certain words appear twice “green”, “upwards” and then this phrase which seems to speak both to the literal idea and to the microscopic and subatomic, “vineyards on the train”. Then there’s this other idea which springs from that, that the poem exists in the creative mind of the reader and now here, in this email which is as disconcerting as it is beautiful.

I think it also implies something poignant about the nature of poetry more generally, that there are – to borrow another phrase – “many worlds” in which a poem might exist. Going back to what you were saying about Penrose, Penrose in the ‘Emperor’s New Mind’, proposes that quantum events occur in the microtubules in the brain. Thoughts are processed in one universe and then return to our own. It is a wild theory, but if, for a moment, we entertain the thought, despite how preposterous – in a way, the idea – that he is right, then perhaps what we read on the page acts as a gateway from one universe into another. Certainly in terms of our own experiences, memories and creativity, nothing could be truer.

Thank you very much for taking the time to respond to my emails, and sorry that I didn’t manage to answer more of your questions, I hope that we can pick up on this in future conversations and keep the dialogue going.

Signing off,

Harry

**

Hi Harry,

Thank you! It’s been fascinating. I feel the same way. The subject is massive and growing. I feel we’ve only scratched the surface. I don’t think we could be in a more exciting period in terms of scientific discovery – on the brink of viable extensive space travel, quantum computing, the search for potential life-sustaining exoplanets, and harnessing the power to mimic the first moments of the universe. This is an opinion formed completely from my own naive and egotistical conjecture, but I reckon we’ll see the next Newtonian/Einsteinian-level paradigm change within our lifetimes. And it’s inevitable with such shifts, in concepts, language, and perspective, that this has a huge impact on art.

The thin balance of precise human calculations on the remorseless powerful flux of nature is palpable. It’s an incredible and awful story. I saw a satellite in the sky the other night and imagined it was the ISS. Whenever I see images of it, the space station seems so vulnerable with its long spindly solar arrays, the threat of impact from space junk seems so constant. I’m sure you must have seen Chris Hadfield’s cover of David Bowie’s ‘Space Oddity’which he filmed in the space station just before he left. It struck me as so poignant that the words that Bowie wrote in the 60s could be sung in real-life anti-gravity, against the backdrop of the glowing planet: ‘Planet Earth is blue and there’s nothing I can do’. Though the original song narrative reaches a disastrous end, the imagery is simple and moving, as though to say – there we all are, that’s all there is to it – is enough. I felt as though the human imagination was so potent as to reach out with words and experience the inexperienced and the unknown.

The many individual readings of a single poem, interpretations, personal preoccupations and associations all contribute to the ‘many worlds’ of a poem. Those physicists who believe in the multiverse theory as a truth in reality believe that everything that can happen does happen. Which means that one has done everything it is possible to do, everything that doesn’t break the laws of physics. This implicates that every poem that could feasibly be written, is written. Another wild theory that weirdly, rather than making me feel inconsequential, makes me feel curious about the exact circumstances and conditions in which I live that lead me to place certain words in certain orders. How strange that I can write something that is inherent to a multiverse.

Keep me updated with your readings, poems and musings!

And best wishes,

Ella***

Harry Man was born in 1982, his poetry has appeared in New Welsh Review, Well Versed, Elbow Room, Poems in the Waiting Room, Poems in Which, and Eyewear’s Poetry Focus among other places. He works as a Digital Editor in South London. His first pamphet ‘Lift’ is forthcoming from Tall Lighthouse.

Ella Chappell was born in south Manchester in 1990 and went on to study the BA and MA degrees in Creative Writing at UEA. Her poetry is published or forthcoming in UEA: 17 Poets, The Lighthouse, Elbow Room, Ink Sweat & Tears, a handful of stones, Badrobot Poetry, Et Cetera and #NewWriting. Her recent projects include ‘Null World’, a filmpoem created in collaboration with filmmakers, which will premiere at the national filmpoem festival in Dunbar this August. Ella posts a new poem every day here.