posted by the Judge

Aye aye! It’s Sunday, and it’s also quite cold outside. Since we’re all still enveloped in the white embrace of winter, here at Dr Fulminare we’re bringing you a review that is all about the cold season: two books in one go, one is called Ice, the other is called Skate, both edited by Meredith Collins, and for this special occasion they are being reviewed of course by Jon Snow.

No, hold on a second. Jon Snow was a character from Game of Thrones, the illegitimate son of Eddard Stark. The one I’m probably thinking about is Jon Stone, who works with me at this site. But come to think of it there was another character in Game of Thrones called Mya Stone, who was the illegitimate daughter of Robert Baratheon. What the heck? Are these guys all from the same family?

Never mind. Read the review by clicking on this link while I go ask Kirsten Lannister who was who.

Have a great Sunday!

Category: Uncategorized

When poetry and criticism overlap (On Criticism #3)

We mentioned in our previous articles that there are two main agendas in criticism. In one of them, criticism functions as a consumer guide, informing the reader about the price, quality, category and nature of the object. Though this agenda informs, to a greater or lesser degree, reviews of almost everything, poetry criticism does not share in it at all.

The other main strand of criticism goes by the name of ‘cultural criticism’ (roughly, at least – I don’t want to start haggling with people about the precise definition and/or schools of ‘academic’ cultural criticism). This is the type of material you find in the more intellectual sites; in its purest instances, it shows no interest at all in the question of whether an item of representation is ‘good’ or not. Instead, it is dedicated to a process of analysis, breaking the text down into its constituent parts and revealing its many layers of signification. This is something very different from consumer guidance. In it, the critic is undertaking a process that the reader does not have the means, or perhaps the time, to do in person. The critic exposes him/herself to the work of art multiple times, absorbing it, looking at it in the light of different possible readings, and taking the time to research the history and references behind it; s/he is not simply reporting his/her response to the text (‘I enjoyed it’, ‘I found it boring’, etc.), but providing a new, contextualised and researched interpretation.

The primary role of this type of criticism is to extend the ideological discussion beyond the work of art itself. For many people, the experience of seeing a film ends when they walk out of the cinema. But for those with a deeper interest, engaging with a film means opening a discussion, one which is internal as much as it is social, and one which does not end after the first viewing, but rather furthers itself in many different platforms. It is, among other things, part of an ongoing desire to educate oneself.

None of this should come as some kind of novel or innovative description to anyone who knows a little bit about criticism, and it would probably not be worth writing an article about the ‘intellectual’ register were it not for the one thing that makes poetry criticism unique in this context. To put it concisely, the role of poetry criticism overlaps with that of poetry itself – more so than it does in any other art-form. What do I mean? Well, let us consider a few of the functions of intellectual criticism.

Criticism must educate the taste of the reader, not simply cater to it. It must give a voice to those who do not have one, and this includes any type of minority group; it must also point out instances in which they are being discriminated. It must make us aware of the agenda that lies behind a text, so that it must reveal both the dominant ideology and the language that said ideology uses to manipulate our preferences, choices and actions. It must provide the dispassionate perspective in a forum which may otherwise be steered by interest, money and power. Finally, it must bring our attention to smaller artists or works of art, which demonstrate promise and quality but do not have the means to promote themselves on their own.

With the exception of the very last line, everything that has been said of criticism could be said of poetry as well. Certainly much of it could be said of art in general, but it is especially true with poetry, which has a unique contiguity of form with its criticism. While film reviews are usually not made in film, and music reviews are not put down in song (though that would make for an interesting scenario), literature and literary criticism both express themselves through language. Novels are alike to their reviews in that they’re both predicated on language, but even then, the novel is essentially defined by a narrative – and that’s where it irreparably divorces itself from the review.

Poetry, by contrast, has – in purely formal terms – very much in common with criticism. In both cases, we are dealing with a compact expression of thought, communicated through language. Thus, anything that a poetry review can do, is also something that a poem can do. The opposite, however, does not hold true – though poetry already does everything that criticism can do, criticism most certainly cannot do all the things that poetry can do; and in this sense a poem can be much more than an expression of thought (it can also express, for example, emotions, values and beliefs).

From this point of view, the fact becomes of special interest that poetry is also the most self-referential of all arts. Contemporary poetry overflows with citations, paraphrase and intertextual objects coming from other poetry, both ancient and modern. In fact, often the game is precisely that of figuring out how a poet’s apparently simple statements are in reality a clever critique of other, more established modes of poetry (see the many modes and subtexts of love poetry).

In other words, to a certain extent poetry already reviews itself. This poses a convoluted challenge to the critic – how do you place your review in a discourse that is already reviewing itself? There is no straight answer (alas). A critic must always enter into a dialogue with the collection under scrutiny – and it is in every sense of the word a dialogue, in a way which, as we mentioned, no other art can replicate. But the best way to lead (and eventually report on) that dialogue is something that depends on the individual critic as well as the particular collection. It also depends on who you’re writing for and where your review is going to be published. Though this is not something I personally like to read in other people’s articles, I’ll have to say it – for this particular question, there is no right or wrong answer.

That said, although the challenges posed by the overlapping of poetry and criticism have no universal solution, there is also at least one way in which this idiosyncrasy helps us. Poetry and criticism are both responsible for providing social commentary; thus, poetry criticism is almost meta-criticism, inasmuch as it is an (ideally) socially engaged response to an (ideally) socially engaged response. This is helpful for a very simple reason: it means we can use some of the same standards when reading poetry that we usually apply to criticism.

You can say that a film is ‘entertaining’ or that a game is ‘fun’, but you wouldn’t really say such things of a good review (except perhaps hatchet jobs, but those are a special case). Instead, what seems to matter in a review is that it is informative and well-researched; those of an excellent review, that it challenges preconceptions and shows things in a new light, that it demonstrates an original, independent approach and that it is engaged with the world in which it takes place. All of those things should be true of a good poetry collection as well.

So, even though you may sometimes be a little put back by a collection’s ability to incorporate whatever argument you’re trying to make in your review, you can also use this to your advantage. If you are uncertain whether a given type of praise is adequate for a poetry book, run this little test. Ask yourself, ‘is this something that I would also say about a good piece of criticism?’ If the answer is no, as it would be for colourful but purely descriptive adjectives (this collection is ‘musical’, ‘scintillating’, ‘eclectic’, ‘sparkling’, ‘exciting’, etc.), then it might be a good idea to reconsider what type of argument you’re making.

This is not something that always and necessarily holds true, of course, and it’s not like those adjectives should be banned from reviews or anything. But it’s an amusing detail to be aware of, as it only really subsists in poetry criticism, and sometimes it can help to make things clearer: if you are building your review entirelyon the descriptive terms, then you’re probably just writing film / game / music criticism that happens to be about a poetry collection. And this is something very different from genuine poetry criticism.

Sunday Review: I Am A Magenta Stick by Antony Rowland

posted by the Judge

ROCK ON LADIES AND GENTS!!!!! It’s Sunday, and we’re bringing you our lovely Sunday review as Judi Sutherland reviews I Am A Magenta Stick by Antony Rowland, whom you can see in the above pic in his winter outfit as he tries to fix his magenta stick (technical problems, I am told). He’s a big fish, by the way – latest winner of the Manchester Poetry (assuming that prizes mean anything… see the post below this one).

Click on this link to read the review. If instead you’d rather read on the biology and control of the Mexican prickly poppy, click here.

Have a great Sunday!

ROCK ON LADIES AND GENTS!!!!! It’s Sunday, and we’re bringing you our lovely Sunday review as Judi Sutherland reviews I Am A Magenta Stick by Antony Rowland, whom you can see in the above pic in his winter outfit as he tries to fix his magenta stick (technical problems, I am told). He’s a big fish, by the way – latest winner of the Manchester Poetry (assuming that prizes mean anything… see the post below this one).

Click on this link to read the review. If instead you’d rather read on the biology and control of the Mexican prickly poppy, click here.

Have a great Sunday!

Farzaneh Khojandi, and the English / Persian poetry relation

In November of 2012, we published a negative review of the pamphlet ‘Poems’ by Persian author Farzaneh Khojandi, which ended with a call for elucidations. This is the first article we have received in response, written for us by Maryam Fathollahi. The editors would like to thank her for her time and effort.

Can Persian poems be understood with effortless ease, and are their pleasures immediately accessible? They can and are with due time, but one must familiarise oneself with the culture, and mature works should be picked as a starting point. Let us discuss the issue with respect to the work of Khojandi, a contemporary poet from Tajikistan.

When I first finished the draft for this article, I forwarded it to a knowledgeable expert to have his opinion. After reading the paper, he told me “your article is full of Persian metaphors and beautiful figures of Persian speech, but translating it into fluent English would be a difficult, complicated matter. An article needs transparent and tangible words.” Our discussion on this subject encouraged me to research several aspects concerning poetry translation. First of all, it became apparent to me that poetry translators should have a strong understanding of the view, the emotion, and the culture of their readers. In addition to this, they should of course adhere to the original concepts presented in the source text and indeed they should try to reproduce the poetic form. Poetry translation is therefore much more challenging than the translation of ordinary texts.

Farzaneh Khojandi is a poet from Tajikistan; her last name derives from the name of her birthplace, Khojand. She has published several poetry books and is nowadays considered the head of poets in Tajikistan, primarily owing to her lyric poems; it is through these poems that she came to be known as “the Forough of Tajikistan”.

“Forough of Tajikistan” may refer to two distinct meanings. Firstly, “Forough” is a Persian word meaning brilliance, brightness, light and shining. It therefore signifies that Farzaneh Khojandi is like a sun shining over the literature of Tajikistan. On the other hand “Forough” reminds me of a female intellectual and prominent Iranian poet, Forough Farrokhzad, sometimes called “the Forough” in Iran.

Will Farzaneh Khojandi of Tajikistan become another Forough Farrokhzad? Will her works find a wide readership? Before tackling these questions, let us provide a brief overview on the relationship between the Persian and English languages.

In the late eighteenth-century Sir William Jones (Youns Uksfardi) noticed the existence of a close relation between certain Indo-European languages. In fact, some other scholars before Jones had already noticed that a family of languages (namely German, English, Persian, and others) share the same root. But how did they develop into their differences? I believe the primary reason has to do with their cultural evolution, relative to their individual nations. A good example of this is the interaction of culture for people who live in Iran and Tajikistan. However, Farsi is a principal joint.

Furthermore, the nineteenth-century saw the beginning of serious inspections of language. Studies of researchers show that language is a social intuition continuously altering. Given this premise, it follows that translation is a correspondently dynamic process. I tend to think that translation must import culture by conveying its concepts, but on the other hand, it will also deform the source poetry. As a result, it will mean a loss of the poetry’s original aesthetic vision.

It seems to me we need more to know about the process of translation behind Khojandi’s poems. Have the translators conveyed the meaning of her poetry under her judgement?! And have they thought of her English readers? It is necessary to hear her opinion on the matter because Iran is a land of civilization and great poets. In a not-so-distant past, many neighbouring countries of Iran – such as Tajikistan – were provinces of modern Iran. Farsi was thus the common language between them. Poets such as Rudaki, Khayyam, Ferdowsi, Rumi, Hafez and Saadi, as well as contemporary poets such as Nima Yooshij, Ahmad Shamloo, Forough Farrokhzad, Sohrab Sepehri are Iranians who have written Farsi poetry.

Of course, Farsi poetry consists of a variety of figures of speech. These include: rhyme, metaphor, imagery symbolism, oxymoron, synaesthesia, personification, ambiguity, defamiliarisation and others. Through these, Persian poetry works like a painting or a film to allow readers to evince a lofty ideal from it. To be more precise, figures of Persian speech are the best aesthetic aspect of Persian poetry. And yet a correct translation of Persian poetry must be familiar with the culture and the background behind the use of certain words (in Farsi).

In the final analysis, although English is already an international language, we require an organization or an institution to include all of the world’s poets and translators in an effort to improve the process of translation. Moreover, it would be a good idea to produce an encyclopedia (by these very poets and translators) in order to simplify translation and decipher figures of speech with respect to the cultural diversity of their lands of origin. Therefore, there needs to be an endless communication with poets and translators of the world to start new studies and to better understand poetry from all countries, including the beauty of Persian poetry.

Maryam Fathollahi was born in 1982 in Tehran (capital of Iran). She has a BA and is currently studying French translation. She started writing poetry in 1997 and has won local competitions in Persian poetry in 2001 and 2005, in Tehran. Her first Persian poetry book was published in 2008, under the title The Beautiful Mares. She is also the author of a script that she completed in 2012. She is currently writing a novel and is editing her second Farsi collection, entitled The Expectation.

Can Persian poems be understood with effortless ease, and are their pleasures immediately accessible? They can and are with due time, but one must familiarise oneself with the culture, and mature works should be picked as a starting point. Let us discuss the issue with respect to the work of Khojandi, a contemporary poet from Tajikistan.

When I first finished the draft for this article, I forwarded it to a knowledgeable expert to have his opinion. After reading the paper, he told me “your article is full of Persian metaphors and beautiful figures of Persian speech, but translating it into fluent English would be a difficult, complicated matter. An article needs transparent and tangible words.” Our discussion on this subject encouraged me to research several aspects concerning poetry translation. First of all, it became apparent to me that poetry translators should have a strong understanding of the view, the emotion, and the culture of their readers. In addition to this, they should of course adhere to the original concepts presented in the source text and indeed they should try to reproduce the poetic form. Poetry translation is therefore much more challenging than the translation of ordinary texts.

Farzaneh Khojandi is a poet from Tajikistan; her last name derives from the name of her birthplace, Khojand. She has published several poetry books and is nowadays considered the head of poets in Tajikistan, primarily owing to her lyric poems; it is through these poems that she came to be known as “the Forough of Tajikistan”.

“Forough of Tajikistan” may refer to two distinct meanings. Firstly, “Forough” is a Persian word meaning brilliance, brightness, light and shining. It therefore signifies that Farzaneh Khojandi is like a sun shining over the literature of Tajikistan. On the other hand “Forough” reminds me of a female intellectual and prominent Iranian poet, Forough Farrokhzad, sometimes called “the Forough” in Iran.

Will Farzaneh Khojandi of Tajikistan become another Forough Farrokhzad? Will her works find a wide readership? Before tackling these questions, let us provide a brief overview on the relationship between the Persian and English languages.

In the late eighteenth-century Sir William Jones (Youns Uksfardi) noticed the existence of a close relation between certain Indo-European languages. In fact, some other scholars before Jones had already noticed that a family of languages (namely German, English, Persian, and others) share the same root. But how did they develop into their differences? I believe the primary reason has to do with their cultural evolution, relative to their individual nations. A good example of this is the interaction of culture for people who live in Iran and Tajikistan. However, Farsi is a principal joint.

Furthermore, the nineteenth-century saw the beginning of serious inspections of language. Studies of researchers show that language is a social intuition continuously altering. Given this premise, it follows that translation is a correspondently dynamic process. I tend to think that translation must import culture by conveying its concepts, but on the other hand, it will also deform the source poetry. As a result, it will mean a loss of the poetry’s original aesthetic vision.

It seems to me we need more to know about the process of translation behind Khojandi’s poems. Have the translators conveyed the meaning of her poetry under her judgement?! And have they thought of her English readers? It is necessary to hear her opinion on the matter because Iran is a land of civilization and great poets. In a not-so-distant past, many neighbouring countries of Iran – such as Tajikistan – were provinces of modern Iran. Farsi was thus the common language between them. Poets such as Rudaki, Khayyam, Ferdowsi, Rumi, Hafez and Saadi, as well as contemporary poets such as Nima Yooshij, Ahmad Shamloo, Forough Farrokhzad, Sohrab Sepehri are Iranians who have written Farsi poetry.

Of course, Farsi poetry consists of a variety of figures of speech. These include: rhyme, metaphor, imagery symbolism, oxymoron, synaesthesia, personification, ambiguity, defamiliarisation and others. Through these, Persian poetry works like a painting or a film to allow readers to evince a lofty ideal from it. To be more precise, figures of Persian speech are the best aesthetic aspect of Persian poetry. And yet a correct translation of Persian poetry must be familiar with the culture and the background behind the use of certain words (in Farsi).

In the final analysis, although English is already an international language, we require an organization or an institution to include all of the world’s poets and translators in an effort to improve the process of translation. Moreover, it would be a good idea to produce an encyclopedia (by these very poets and translators) in order to simplify translation and decipher figures of speech with respect to the cultural diversity of their lands of origin. Therefore, there needs to be an endless communication with poets and translators of the world to start new studies and to better understand poetry from all countries, including the beauty of Persian poetry.

Maryam Fathollahi was born in 1982 in Tehran (capital of Iran). She has a BA and is currently studying French translation. She started writing poetry in 1997 and has won local competitions in Persian poetry in 2001 and 2005, in Tehran. Her first Persian poetry book was published in 2008, under the title The Beautiful Mares. She is also the author of a script that she completed in 2012. She is currently writing a novel and is editing her second Farsi collection, entitled The Expectation.

Sunday Review: Robert Stein’s ‘The Very End of Air’

posted by the Judge

It’s my turn back at the reviewing board, and this Sunday I’m giving a twirl to Robert Stein‘s The Very End of Air. You can find the review here.

It was actually an interesting article to write. The collection itself was a mixed bag, but those aspects that I did not like were very much worth exploring, as I don’t think they are exclusive to Stein at all (not even exclusive to poetry, in fact).

Have a great Sunday, or should I say, a great Sunday night!

It’s my turn back at the reviewing board, and this Sunday I’m giving a twirl to Robert Stein‘s The Very End of Air. You can find the review here.

It was actually an interesting article to write. The collection itself was a mixed bag, but those aspects that I did not like were very much worth exploring, as I don’t think they are exclusive to Stein at all (not even exclusive to poetry, in fact).

Have a great Sunday, or should I say, a great Sunday night!

Sunday Review: Night Journey by Richard Lambert

The Judge is away this week, no doubt quaffing a lovely single malt on a tatami mat just south of Felixstowe or somesuch, but we’re bounding right into 2012 with the Irregular Features Sunday Review. This week Harry Giles gets going with Night Journey by Richard Lambert, published by Eyewear.

Sunday Review: The Lucky Star of Hidden Things by Afric McGlinchey

posted by the Judge

Not sure if Santa’s going to be reading this one, with all the stuff’s he’s got to go through, but here’s our Sunday review: Ian Chung takes a nice long look at Afric McGlinchey’s The Lucky Star of Hidden Things.

Take a nice long look at his review, via the above link.

Have a fantastic New Year’s, and end it the way you began the day. (That would be: lying down. If you began it by doing something else, then by all means do something else).

Not sure if Santa’s going to be reading this one, with all the stuff’s he’s got to go through, but here’s our Sunday review: Ian Chung takes a nice long look at Afric McGlinchey’s The Lucky Star of Hidden Things.

Take a nice long look at his review, via the above link.

Have a fantastic New Year’s, and end it the way you began the day. (That would be: lying down. If you began it by doing something else, then by all means do something else).

I’m Walking Backwards (but looking forwards) for Christmas

Just a quick post to say thank you to everyone for a great year. Sidekick Books has had a tiring but good 2012, putting out the second part of our four-volume tribute to Britain’s birds, Birdbook II: Freshwater Habitats, and the long-awaited print version of Simon Barraclough’s Hitchcock tribute Psycho Poetica.

Whether you’ve written for us, illustrated for us, bought books, come to readings, evangelised about our strange schemes online or simply investigated the dark world of Dr Fulminare in passing, we appreciate it and will continue to provide characteristically Sidekick weirdness in 2013.

K x

Whether you’ve written for us, illustrated for us, bought books, come to readings, evangelised about our strange schemes online or simply investigated the dark world of Dr Fulminare in passing, we appreciate it and will continue to provide characteristically Sidekick weirdness in 2013.

K x

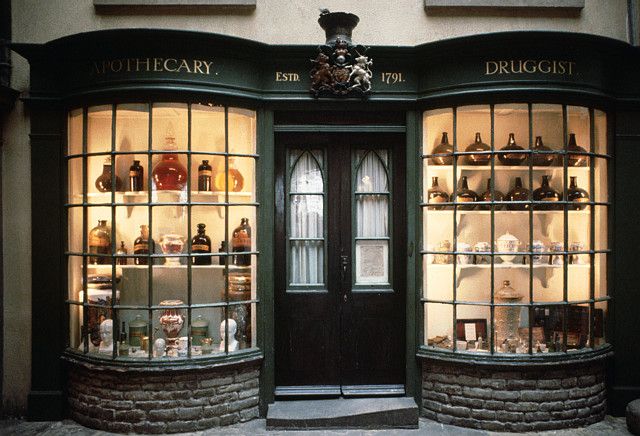

Sunday Review: The Apothecary’s Heir, by Julianne Buchsbaum

posted by the Judge

The last Sunday before Christmas. A silent night, a holy night… no-one mentioned it was supposed to be such a COLD night.

To warm your spirits, here’s some Baileys… nah, I kid, I kid. What I can give you instead is our Sunday review, which deals with Julianne Buchsbaum‘s The Apothecary’s Heir. It’s a pretty big deal, as it’s been chosen yonder in the US of A for the National Poetry Series. Rowyda Amin, our specialist beyond the Atlantic, tells us all about it in the article.

What the heck, it’s impossible not to close with these words. Merry Christmas everyone, and have a glorious 2013!!

Christmas Chiller

In a departure from my generally poetically-inclined endeavours, I’ve written a short five-part Christmas horror story, which will be serialised by Popcorn Horror over their smartphone/tablet app and website from 21-25 December. It’s called Krampus Inc. How to summarise it? Well, suppose the European legend of a Yule devil were true, and he’d been taking tips from humanity in how to get his own way …