An occasional (possibly one-off) series in which members of the Sidekick team take on received wisdom and unchallenged proclamations from on high.

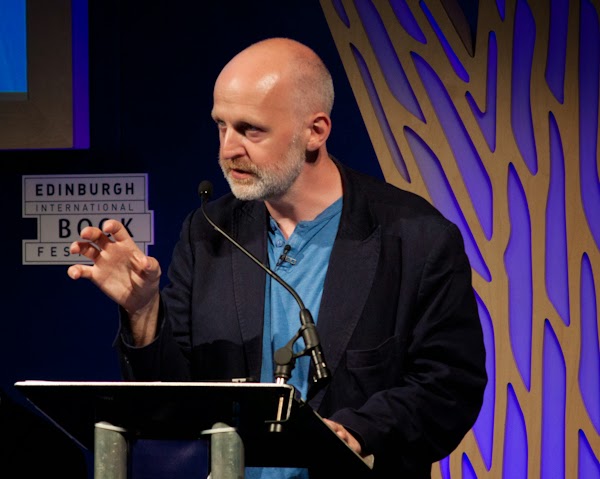

When writing about the craft of poetry, there’s a popular mode of address which mingles mystagoguery with aphoristic instruction, often eschewing (or even contradicting) practical advice in favour of the ear-pleasing commandment. Don Paterson’s entry in the Letters to a Young Poet series on Radio 3 is an example of such an address. Throughout its 13 minutes, Paterson juxtaposes a lugubrious, teacherly tone with the pseudo-profundities of a pub philosopher. He is drunk, of a fashion – that is, intoxicated with reverence for the methodology that produces a particular strain of poetry, with love of the paradoxical and the dramatic, with the sense of his own authority.

The italics below are transcribed from the broadcast.

Young friend, you ask me if your verses are any good. The answer is: no, not yet. You knew this because you had to ask.

Paradox has a way of sounding like wisdom, but “You knew this because you had to ask” falls far short of the insight it aspires to. Level of reassurance sought is in no way related to the quality of a person’s writing or their awareness of it. Some people are brilliant and don’t know it. Others are insulated by confidence against the chill of their own mediocrity. It isn’t foolish to ask for a second opinion, just so long as you learn to cultivate your own sense of when a piece of writing is sufficiently accomplished, which will happen in time.

Those youthful geniuses we like to invoke mostly had foreknowledge of their own early deaths.

Very romantic, very unlikely. A more realistic explanation for the apparent brilliance of a few very young poets of past eras is the relative lack of distraction and the right context, the right emotional make-up, for obsessive devotion to an art, coupled with our cultural tendency to shape our aesthetic values around what they wrote.

The world needs more readers, not more poets.

At this early point in the address, Don begins to entertain (and later returns to) the seductive idea of poetry as a mad and dangerous pursuit, undertaken only by the fever-ridden few, the damned. It’s a clever kind of circle-pissing that avoids looking like elitism by making grotesques out of the implied elite.

But it’s perfectly acceptable to experiment lightly with writing poetry or to find your way towards it gradually. Attempts to warn people off, particularly from the incumbent hegemony, should be regarded with skepticism.

Poetry is not a calling but a diagnosis.

I liked it when Leonard Cohen said “Poetry is a verdict, not an occupation” and I like this. But neither is anything more than a playful aphorism. Comparing poetry to dyslexia and bipolar disorder, as Don goes on to do, is crude and untruthful. Being hopelessly predisposed towards an activity is not the same as having a mental illness or a disability.

If you feel you can choose, then choose no …

Make no mistake: Don Paterson chose to write poetry. If writing poetry in this culture were punishable by death or castration, he may very well not have done so.

Firstly, and most importantly, don’t ever think of yourself as a poet.

Or do. It isn’t important whether you think this or not, except to the degree it makes you comfortable or uncomfortable. Just don’t believe that because you’re a poet, whatever you write is poetry, that the status itself imbues your words with authority. Too many established poets make that mistake.

‘Poet’ describes an activity, like ‘murderer’, not a permanent disposition.

This stands in apparent contradiction to his ‘poetry as diagnosis’ position, and makes for a strange comparison, because a murderer doesn’t stop being a murderer mere moments after he’s done murdering. Don’s ensuing extended metaphor of the murderer-poet is appealing because we like to characterise ourselves as creatures of dramatic action and bloodiness. But there is little truth here. A statement like ‘unlike other artists … we do other things too’ is bafflingly opaque. What ‘other artists’? What do we do that they don’t? He then suggests that you should plan your first published poem like an assassination, expecting not to get away with it if it’s anything less than perfect. In fact, poets get away with bad published poems all the time, and you will too. Expect your most carefully crafted poems to be passed over by editors in favour of something you tossed together at the last minute. Expect to have to change your mind repeatedly about any work that is important to you, particularly when it appears in print for the first time.

Also, because the investigator of the successful poet becomes more relaxed and accommodating, while the investigator of the murderer grows ever more determined and scrupulous, poets also have a tendency to get sloppier with time, while murderers become more proficient – the exact opposite to what Don asserts here. It’s a terrible series of points.

Skipping to the more fundamental parts:

To write poetry is the ultimate presumption. It says ‘I have something important to say’.

There is no reason to apply this to poetry in particular over other art forms. Nor is there any reason to suppose a poet means to say something ‘important’, rather than something merely interesting or pleasing.

Don is betraying here his own predilection for poetry of proclamation and revelation. It’s the first big clue that he’s not really talking about poetry at all; he’s talking about ‘poetry in the style of Don Paterson’.

You can’t steal a poem, even from yourself.

But you can steal a poem, both in the sense of appropriating words already written, and in the sense of the poem flowing easily from a sentiment, conceit or compulsion. Perhaps Don is advising here that we don’t rely on these shortcuts because they are few and far between. More realistically though, he is suggesting that a poem isn’t a poem (in the Don Paterson mould) until it has been through the forge of writerly concentration, been won through labour.

As advice, this is about as helpful as being told that wealth can only be acquired by starting at the bottom of a company and working your way up. It just doesn’t engage with the nature of creative writing – particularly a short form like the lyric poem, which can slide into view or throw itself upon you just as much as it can be forced to work through hours, days, weeks or months of careful attention.

Subject matter is mere pretext to write about something else.

It’s hard to disagree entirely with this because it describes an approach that works for many poets. But this absolutism is phony. He’s showing us the source of a river and telling us it’s where all the water in the sea comes from. Sometimes a poet who decides to write a poem about a fox writes a poem about a fox, and sometimes the poem ends up being about something else entirely.

If you sit down already knowing what you’re going to write, stop, because so does the reader.

Don says this after dispensing another colourful-but-reductive analogy – humanity as coral reef, all thinking the same thought. In Don’s eyes, the ‘unexpected’ – that element of poetry that ought to be treasured – can only arrive through process, and thus the point of a poem is only discovered as the writer nears completion, having written it ‘backwards’. I don’t see any reason for his making this assumption on behalf of other people, even if it’s how his own mind works. It strikes me more as ex post facto justification than intellectual discovery, and an excuse for a lack of ambition (or perhaps narrowness of ambition) when starting out with a blank page. It is entirely possible to begin writing with a grasp on how the poem will move towards the unexpected.

One should also not treat Don’s methodology as a guarantee against the drift towards banality. It is still a formula, and like all formulae, it returns results that grow more familiar as they accumulate.

The darker truth is that you will stand out in thunderstorms flying a kite, or in bad weather be tempted to summon your own tempest.

Yes, cognitive bias means that people who are too greedy for ‘poetic’ subject matter will tend to find melodrama wherever they look. Don seems to be going so far, though, as to suggest that poets create problems for themselves in order to write about them. I’d suggest that most people have enough problems and merely suffer from thinking that they ‘should’ write about them, even when not particularly inspired. This is the fault, I’m sorry to say, of too many prizes given to poems about dead parents. It doesn’t mean you should distrust genuine inspiration.

Remember, form is your friend. It makes poems both easier and harder to write. Harder because it will prevent you from saying the one thing you wanted to say, which is often dull, weak and commonplace, and easier, because form forces you to say something else …

Although he lays it on with a trowel (up to and including the claim that this is what your reader ‘demands’ of you), I agree with Don about form. I suspect he may be talking only about traditional form, though, rather than form in all its possibilities.

Remember your unconscious is your unconscious for a good reason.

The conscious/unconscious isn’t a very useful dichotomy when talking about writing. I would suggest that there are things toward the edge of one’s mind, things that hide in plain sight, and things that can and ought to be drawn further into the light.

The truly original idea must be part familiar, so that it can take the reader on a journey from the known to the unknown.

Ah, this business of taking readers on journeys. Here, as far as I can tell, Don is railing against writing anything that is too overtly alien, but how does he, or anyone else, know what is familiar or unfamiliar to a particular reader? What if the reader is in search of the alien? The trap Don has fallen into is identifying a pleasing effect and imagining (a) it is the pleasing effect, and (b) that it can be planned for. But anyone who has ever found themselves baffled and dismayed by other readers’ enthusiasm or glowing testimonials will know that there is no formula for emotional impact. Advising us to set out to perform this particular trick is like telling us to develop a rapport with everyone we meet, and to do so using only gentle and placatory gestures.

The most fruitful risks will involve writing at the extremes of emotion just before it shades into sentimentality, writing simply just before it shades into foolishness and with prophetic force just before it shades into pretentiousness.

This, again, looks a lot like wisdom – because of course one should always stop short of sentimentality, foolishness and pretentiousness, if one can. Don goes on to use the analogy of the puffer fish being prepared so that just a little toxin from the poison sac seeps into the flesh – just not enough to kill. It is, again, a dramatic and appealing analogy. But really, there is no such fine line. Most poetry, I would suggest, finds itself appearing sentimental, foolish or pretentious to some readers as the necessary price for impressing others. That’s the nature of spellcasting. Gunning for prophecy, simplicity and/or profundity, meanwhile, is as natural an instinct as there is in writing, so that this very elaborate and neatly worded passage of Don’s address really amounts to “Aim to reach the finish line as fast as you can, but try not to stumble”. It has nothing to do with risk.

Risk in poetry is a more fiddly thing to unpack. It might mean, for example, writing to a form or in a manner or on a subject that you know is unfashionable or overtly disapproved of so that there is very little chance of meeting the criteria set forth by those with the most influence, who are in a position to promote or deny your work. It means being prepared to write a poem that is unlikely to get any airing at all unless you are able to smuggle it in under the watchful eyes of the gatekeepers, or unless you catch a wave of changing fashions.

Being ignored, having something to say but finding no one prepared to listen – this is a deeper punishment than simply being seen as pretentious or foolish by a proportion of a small readership. That is why, after all, too many poets conform to the aesthetic expectations of Don and his peers too readily. Some bets are safer than others.

I note at this point that the way in which Don has set about characterising his imaginary correspondent in this address is as someone overtly seeking Don’s approval. Don is really envisioning himself being asked, “How do I write the sort of poem you might consider publishing?” Naturally enough, then, he doesn’t wish to consider the risk of writing a poem that he himself wouldn’t touch. So when he thereafter talks of ‘readers’ or ‘the reader’ –

Readers read poetry to take them closer to something powerful and dangerous that they will not usually be prepared to let themselves feel.

– he is talking about himself. We know readers come to poetry for a whole variety of different reasons. But Don is interested in telling us what he wants from a poem. Earlier in this article, I said it was important to develop your own sense of when a piece is sufficiently accomplished. It’s also important not to mistake that sense for a universal doctrine, which is the mistake Don makes here.

Risk is also bound up in compromise and negotiation. It’s not the case that one simply ‘takes risks’, but that one risks something specific in return for something else. Whose criteria, for example, do you seek to meet, and to what extent, in order to win them over? Don’s correspondent risks ending up lacking individual character in his poetry as a result of seeking guidance as to how to impress Don the reader, how to write poetry in the style of Don Paterson.

We have to take Occam’s Razor and then use it to murder our darlings.

I admire the welding together of two cliches, but this doesn’t mean anything.

Only write half the poem, but precisely the half that will prompt the reader to supply the rest of it …

This is just a cute way of advising against over-explicating. Poets write the whole poem and the part that reader supplies isn’t the poem.

A poem is like an ecosystem – a complex interdependency between a finite number of agents …

This is also true of a bicycle or a table lamp.

Such a poem has harmony as well as melody, and creates the rich context in which we can read its symbols.

What he appears to be saying here is that deftly handled rhyme, repetition and other literary devices can add to the meaning and functionality of a piece as well as looking and sounding pretty. This is true, but we’ve arrived at a point where he’s reiterating the obvious.

And don’t advertise the strange by making it sound strange.

There’s no reason outside of personal preference to follow or ignore this advice. Some people enjoy strange sounds.

The brain will entertain anything that is sung to it first, even things it vowed not to let pass.

Pertinent – this whole essay is an exercise in singing sweetly in order that the listener’s brain entertain (and perhaps accept) what are often very wild assertions. So point proven, I guess.

But never forget that poets are not your audience … There are too many poets for whom the reader is an inconvenience.

‘The reader’ here, once more, is Don himself, so these two statements don’t sit easily with one another. He is counselling against navel-gazing, against writing for the precious few, but his notion of the poor, undoted-upon general reader is a vision of himself in the throne room of every individual’s brain. If there are too many poets for whom the multiplicity of real readers with conflicting and exacting tastes are an inconvenience, Don is one of them.

If you’re a poet, poets may well constitute the bulk of your audience, as it happens. Or they may be a slim wedge of your audience, or all of it or none of it. They certainly constitute the bulk of Don’s audience. And, as he was earlier keen to point out, poets are only poets when they’re writing poetry. You can treat them as people the rest of the time. It’s no crime to write for a small audience, or even an audience of one. Tastes are easily changed, so that the niche becomes mainstream. Plenty of popular artists and entertainers are idiosyncratic enough that it’s possible they’re not thinking of any audience, let alone some nebulous, faceless ‘reader’.

Kurt Vonnegut suggests writing for one person only as a fundamental rule. I suggest writing for someone out there very much like you, and taking the risk that you’re entirely on your own, rather than pandering to inevitably wrong-headed assumptions about what some average person may want or need from you. Alternatively, I suggest writing for an imaginary jury or parliament of individuals, and having some real fun (by which I mean adventures, by which I mean crises) trying to negotiate their irreconcilable differences in taste.